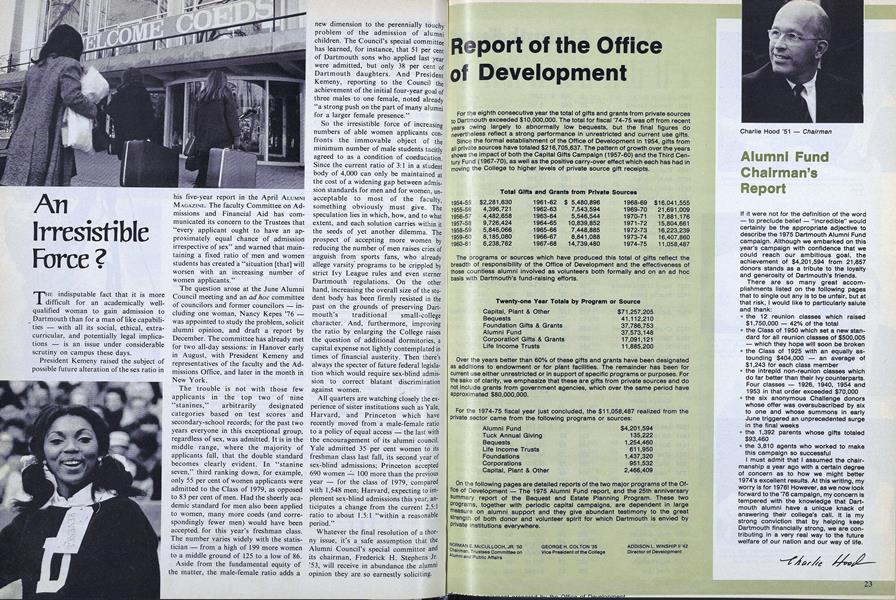

THE indisputable fact that it is more difficult for an academically well- qualified woman to gain admission to Dartmouth than for a man of like capabilities - with all its social, ethical, extracurricular, and potentially legal implica- tions - is an issue under considerable scrutiny on campus these days.

President Kemeny raised the subject of possible future alteration of the sex ratio in his five-year report in the April ALUMNI MAGAZINE. The faculty Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid has communicated its concern to the Trustees that "every applicant ought to have an approximately equal chance of admission irrespective of sex" and warned that maintaining a fixed ratio of men and women students has created a "situation [that] will worsen with an increasing number of women applicants."

The question arose at the June Alumni Council meeting and an ad hoc committee of councilors and former councilors - including one woman, Nancy Kepes '76 - was appointed to study the problem, solicit alumni opinion, and draft a report by December. The committee has already met for two all-day sessions: in Hanover early in August, with President Kemeny and representatives of the faculty and the Admissions Office, and later in the month in New York.

The trouble is not with those few applicants in the top two of nine "stanines," arbitrarily designated categories based on test scores and secondary-school records; for the past two years everyone in this exceptional group, regardless of sex, was admitted. It is in the middle range, where the majority of applicants fall, that the double standard becomes clearly evident. In "stanine seven," third ranking down, for example, only 55 per cent of women applicants were admitted to the Class of 1979, as opposed to 83 per cent of men. Had the sheerly academic standard for men also been applied to women, many more coeds (and correspondingly fewer men) would have been accepted for this year's freshman class. The number varies widely with the statistician - from a high of 199 more women to a middle ground of 125 to a low of 86.

Aside from the fundamental equity of the matter, the male-female ratio adds a new dimension to the perennially touchy problem of the admission of alumni children. The Council's special committee has learned, for instance, that 51 per cent of Dartmouth sons who applied last year were admitted, but only 38 per cent of Dartmouth daughters. And President Kemeny, reporting to the Council the achievement of the initial four-year goal of three males to one female, noted already "a strong push on the part of many alumni for a larger female presence."

So the irresistible force of increasing numbers of able women applicants confronts the immovable object of the minimum number of male students tacitly agreed to as a condition of coeducation. Since the current ratio of 3:1 in a student body of 4,000 can only be maintained at the cost of a widening gap between admission standards for men and for women, unacceptable to most of the faculty, something obviously must give. The speculation lies in which, how, and to what extent, and each solution carries within it the seeds of yet another dilemma. The prospect of accepting more women by reducing the number of men raises cries of anguish from sports fans, who already allege varsity programs to be crippled by strict Ivy League rules and even sterner Dartmouth regulations. On the other hand, increasing the overall size of the student body has been firmly resisted in the past on the grounds of preserving Dartmouth's traditional small-college character. And, furthermore, improving the ratio by enlarging the College raises the question of additional dormitories, a capital expense not lightly contemplated in times of financial austerity. Then there's always the specter of future federal legislation which would require sex-blind admission to correct blatant discrimination against women.

All quarters are watching closely the experience of sister institutions such as Yale, Harvard, and Princeton which have recently moved from a male-female ratio to a policy of equal access - the last with the encouragement of its alumni council. Yale admitted 35 per cent women to its freshman class last fall, its second year of sex-blind admissions; Princeton accepted 690 women - 100 more than the previous year - for the class of 1979, compared with 1,548 men; Harvard, expecting to implement sex-blind admissions this year, anticipates a change from the current 2.5:1 ratio to about 1.5:1 "within a reasonable period."

Whatever the final resolution of a thorny issue, it's a safe assumption that the Alumni Council's special committee and its chairman, Frederick H. Stephens Jr. '53, will receive in abundance the alumni opinion they are so earnestly soliciting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

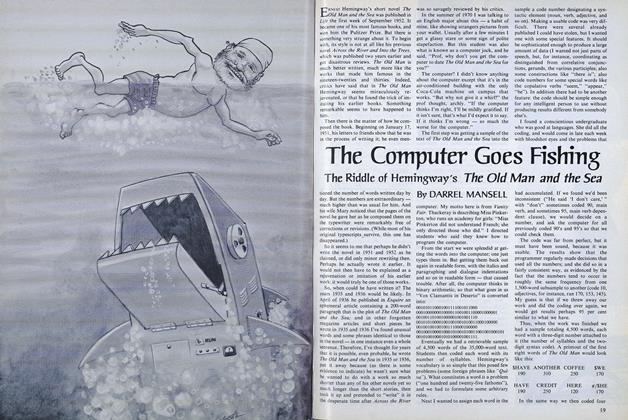

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trials of Reggie

September 1975 By JACK DEGANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ARTHUR L. GOODHART -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYAvenging Angel

NovembeR | decembeR By ERIC SMILLIE ’02 -

Feature

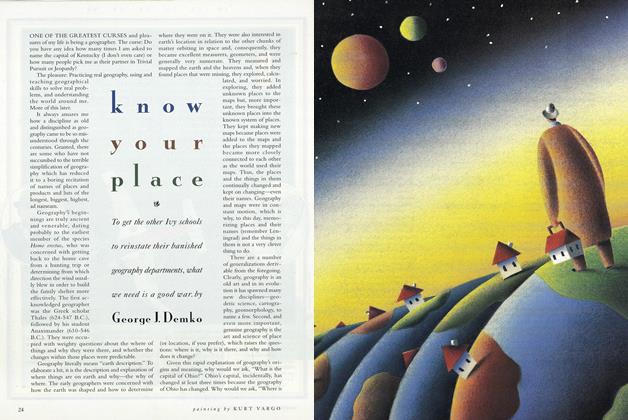

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

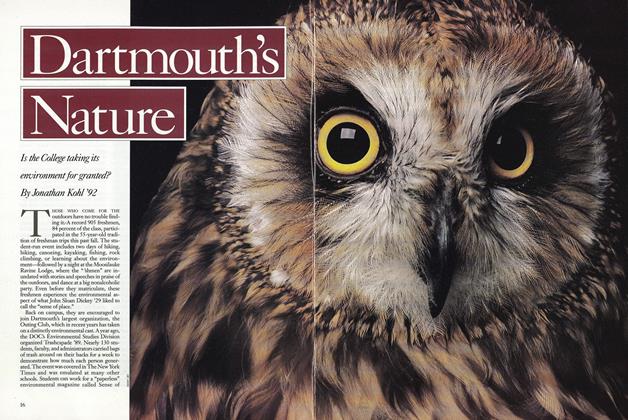

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Nature

December 1990 By Jonathan Kohl ’92 -

Feature

FeatureRugby Posts A Winning Fall Season

DECEMBER 1972 By TREVOR O'NEILL '73