The Riddle of Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea

Ernest Hemingway's short novel TheOld Man and the Sea was published in Life the first week of September 1952. It became one of his most famous books, and won him the Pulitzer Prize. But there is something very strange about it. To begin with, its style is not at all like his previous novel Across the River and Into the Trees. which was published two years earlier and got disastrous reviews. The Old Man is much better written, much more like the works that made him famous in the nineteen-twenties and thirties. Indeed, critics have said that in The Old Man Hemingway seems miraculously rejuvenated, or that he found the trick of imitating his earlier books. Something remarkable seems to have happened to him.

Then there is the matter of how he composed the book. Beginning on January 17, 1951, his letters to friends show that he was in the process of writing it; he even mentioned the number of words written day by day. But the numbers are extraordinary - much higher than was usual for him. And his wife Mary noticed that the pages of the novel he gave her as he composed them on the typewriter were remarkably free of corrections or revisions. (While most of his original typescripts survive, this one has disappeared.)

So it seems to me that perhaps he didn't write the novel in 1951 and 1952 as he claimed, or did only minor rewriting then. Perhaps he actually wrote it earlier. It would not then have to be explained as a rejuvenation or imitation of his earlier work: it would truly be one of those works.

So, when could he have written it? The years 1935 and 1936 would be likely. In April of 1936 he published in Esquire an ephemeral article containing a 200-word paragraph that is the plot of The Old Manand the Sea; and in other forgotten magazine articles and short pieces he wrote in 1935 and 1936 I've found unusual words and some phrases identical to those in the novel - in one instance even a whole sentence. Therefore, I've thought for years that it is possible, even probable, he wrote The Old Man and the Sea in 1935 or 1936, put it away because (as there is some evidence to indicate) he wasn't sure what he wanted to do with a work so much shorter than any of his other novels yet so much longer than the short stories, then took it up and pretended to "write" it in the desperate time after Across the River was so savagely reviewed by his critics.

In the summer of 1970 I was talking to an English major about this - a habit of mine, like showing strangers pictures from your wallet. Usually after a few minutes I get a glassy stare or some sign of polite stupefaction. But this student was also what is known as a computer jock, and he said, "Prof, why don't you get the computer to date The Old Man and the Sea for you?"

The computer? I didn't know anything about the computer except that it's in the air-conditioned building with the only Coca-Cola machine on campus that works. "But why not give it a whirl?" the prof thought, archly. "If the computer thinks I'm right, I'll be mildly gratified. If it isn't sure, that's what I'd expect it to say. If it thinks I'm wrong - so much the worse for the computer."

The first step was getting a sample of the text of The Old Man and the Sea into the computer. My motto here is from VanityFair. Thackeray is describing Miss Pinkerton, who runs an academy for girls: "Miss Pinkerton did not understand French; she only directed those who did." I directed students who said they knew how to program the computer.

From the start we were splendid at getting the words into the computer; one just types them in. But getting them back out again in readable form, with the italics and paragraphing and dialogue indentations and so on in readable form - that caused trouble. After all, the computer thinks in binary arithmetic, so that what goes in as "Vox Clamantis in Deserto" is converted into:

001010110001001111001011000 000100000001000011001001100001000001 001001101001000001001001110 001010100001001001001010011000100000 001001001001001110000100000 001000100001000101001010011001001000101 001010010001010100001001111.

Eventually we had a retrievable sample of 4,500 words of the 35,000-word text. Students then coded each word with its number of syllables. Hemingway's vocabulary is so simple that this posed few problems (some foreign phrases like "Queva"). What constitutes a word is a problem ("one hundred and twenty-five fathoms"), and we had to formulate some arbitrary rules.

Next I wanted to assign each word in the sample a code number designating a syntactic element (noun, verb, adjective, and so on). Making a usable code was very difficult. There were several already published I could have stolen, but I wanted one with some special features. It should be sophisticated enough to produce a large amount of data (I wanted not just parts of speech, but, for instance, coordinating as distinguished from correlative conjunctions, gerunds, the various participles; also some constructions like "there is"; also code numbers for some special words like the copulative verbs "seem," "appear," "be"). In addition there had to be another feature: the code should be simple enough for any intelligent person to use without producing results different from somebody else's.

I found a conscientious undergraduate who was good at languages. She did all the coding, and would come in late each week with bloodshot eyes and the problems that had accumulated. If we found we'd been inconsistent ("He said 'I don't care,' " with "don't" sometimes coded 90, main verb, and sometimes 95, main verb dependent clause), we would decide on a number, and ask the computer for all previously coded 90's and 95's so that we could check them.

The code was far from perfect, but it must have been sound, because it was usable. The results show that the programmer regularly made decisions that used all the numbers; and she did so in a fairly consistent way, as evidenced by the fact that the numbers tend to occur in roughly the same frequency from one 1,500-word subsample to another (code 10, adjectives, for instance, ran 170, 153, 145). My guess is that if we threw away our work and did the coding over again, we would get results perhaps 95 per cent similar to what we have.

Thus, when the work was finished we had a sample totaling 4,500 words, each word with a three-digit number attached to it (the number of syllables and the two- digit syntax code). A printout of the first eight words of The Old Man would look like this:

$HAVE ANOTHER COFFEE $WE 190 310 250 170 HAVE CREDIT HERE #/$HE 190 250 120 170

In the same way we then coded four other samples of Hemingway's fiction. First, one from the novel To Have andHave Not. written at intervals during the period 1933 to 1937. Next, the short story "The Capital of the World," finished in March 1936. Then the work published posthumously under the title Islands in the.Stream and written at intervals from 1940 to perhaps 1951. And last, Across theRiver and Into the Trees, written in 1949 and 1950.

I chose these works because their dates of composition are fairly certain, and span the period from 1933, the earliest I think Hemingway could have written The OldMan, through 1935-36, when he may actually have written it, to 1950, close to the time he himself said he wrote it.

We now had five samples, totaling 22,500 coded words. From various books and articles I got some ideas concerning what to try to count or measure, and these I supplemented with a few of my own. The result was a list of nine "measures," including the total number of each syntax code in the sample; the ratio of main verbs to adjectives, main verbs to adverbs; and the average number of words intervening between main verbs; between verbs in subordinate clauses.

We programmed the computer to get us these nine statistics (one, a complicated measurement of word repetition inside a 100-word grid moving word-by-word through the sample, caused the computer to give official notification of an impending nervous breakdown, and we abandoned it). What follows is a facsimile of the print-out for number 4, the average number of words per sentence. The abbreviations in the left column refer to the title of the work ("COW" is "The Capital of the World") and the numbers identify the 1,500-word subsamples:

SENCNT 11/21/72 10:07NO. OF AVG.SAMPLE SENTENCES LENGTH OMS1 75 19.84 OMS2 88 16.8977 OMS3 110 13.5909 HAVNOT1 136 10.8897 HAVNOT2 195 7.61026 HAVNOT3 191 7.82723 COW1 60 24.9333 COW2 132 11.2652 COW3 97 15.4227 STREAM1 148 10.1081 STREAM2 179 8.36872 STREAM3 179 8.19553 TREES1 134 11.0896 TREES2 162 9.2284 TREES3 144 10.3056

Anyone anxious to know the computer's final "answer" at the end of the project can find a hint here.

We had eight tables like the one above, and we put them all together in one master table, with the 15 subsamples in the vertical column and the eight tests in the horizontal. The computer was then instructed:

In the table find which of the testsshow the least amount of deviationfrom subsample to subsample withina sample, and the greatest amount ofdeviation from sample to sample.

The reasoning here is that the tests which best fulfill this requirement are the tests most effective at differentiating the samples one from another; whatever is being measured remains fairly constant from one independent part of the sample to another when compared to the difference relative to that measurement in all the other samples.

To do this we had to get the advice of an expert, Professor Victor McGee at Tuck School. He told us to subject the results of our eight measurements (average number of words per sentence, and so on) to something called the "F-test," which is widely used in the validation of psychology experiments. This test gives an index number of how reliable each measurement is as a way of discriminating one sample from another; the higher the number the more reliable.

This way we found what were our most reliable statistics, and we were ready for the final step. We used these statistics to look for significant differences according to a formula between each sample of Hemingway's writing and the other four. Put the other way around, we looked for cases where there isn't any significant difference. We got a printout showing these cases for each of our qualifying measurements. Here at last we are beginning to get the computer's "answer" from that vast amount of data. For our first measurement, the total number of each syntax code, the printout appeared as follows. The line connects works not significantly different, hence statistically comparable or the "same":

CODE 10 STREAM HAVNOT TREES OMS COW 11 STREAM TREES HAVNOT COW OMS 20 COW OMS TREES STREAM HAVNOT 21, 22 didn't qualify to give an answer 30 HAVNOT TREES STREAM COW OMS

And so on through all the qualifying measurements.

The computer's "answer" here is equivocal - as seems true of most oracles. But nevertheless something decisive is emerging: for only 17 times was the computer willing to draw a line connecting TheOld Man to a single other work (thereby saying "these two are 'alike' "), and of these 17, 12 connected it to the short story "The Capital of the World" - written in 1936. This is a rudimentary answer: the computer is saying, "Of the four dated works you asked me to compare The OldMan to, it is decisively more like the 1936 work than like the other three."

A statistician can sharpen the answer considerably, by arranging the data in the order of how statistically significant they are as a means of discriminating one thing from another. Hence the table below:

OMS 1/2 1 3/2 2 F=3 4 14 3 9 4 12 3 7 3 11 2 6 1 7 1 3 5 2 11 1 6 2 10 1 5 2 10 1 5 1 7 1 3 7 1 7 1 3 1 6 1 2 1 6 1 2 1 4 1 1 9 1 4 1 3 1 4 1 2 1 4 1 2 1 3 1 1 To Have "Capital" Islands Across

As you move either to the right in the table, or down, the effect is to impose on the comparisons a more and more statistically discriminating filter: to the right, comparisons of The Old Man to the other works based on fewer and fewer of the measurements (like sentence length), but the measurements themselves based on more and more raw information. And going down, measurements more and more statistically significant according to the Ftest as a means of determining the likeness or unlikeness of one sample to another. Thus the right side of the table and the bottom have eliminated all but the most significant comparisons. The computer's "statement" appears in its simplest and most essential form. The second set of digits, indicating the 1936 "The Capital of the World," leaps high above the others. Here at its most decisive is what the computer has to say: The Old Man and the Sea is much more "like" something written in 1936 than it is like the other works.

One step remains - which not everyone will want to take. Did we "date" the novel 1936, when "The Capital of the World" was written? A reasonable answer might be, "That depends on a lot of things" - indeed it does. Also, it's no secret the project turned out to have a number of more or less serious flaws. Therefore, it seems best to conclude guardedly that the computer, using a large amount of syntactic information, and using statistical methods that I think are as free of personal bias as we could have made them, found much more resemblance between The Old Manand the Sea and something Hemingway wrote in 1936 than something he wrote in the periods 1949 to 1950, or 1940 to 1951, or 1933 to 1937.

I want to leave it at that. I would have little faith in the answer if it didn't support an idea I believe in anyway. But surely it is worth emphasizing that the computer did give an answer, a very emphatic answer. I undertook the project because it seems possible The Old Man and the Sea was not written at the universally accepted date, but in 1935 or 1936 - and the computer, with no encouragement from me that I'm honestly aware of, said 1936.

Hemingway broods after The Old Man and the Sea won him the Nobel Prize in1954. He wrote it, according to a pressreport at the time, because "I was broke."But he wasn't broke in the mid-1950s whenthe marlin at left was caught off the Cubancoast and when the computer thinks thebook was probably written.

In the movie version Spencer Tracy, playing the old man Santiago, vainly tries tosave his fish and his dream. Hollywood'sefforts left Hemingway feeling defeated,too. He tried - vainly - to catch a bigmarlin for use in the picture, and to himTracy looked "fat and rich" and the boyManolo "like a cross between a tadpoleand Anita Loos."

A specialist in Victorian literature andEnglish literary criticism, ProfessorMansell joined the Dartmouth faculty in1962. Parts of this article were publishedpreviously in Computers and the Humanities (July 1974) and an account ofthe biographical and textual evidence willappear in the 1975 edition of the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

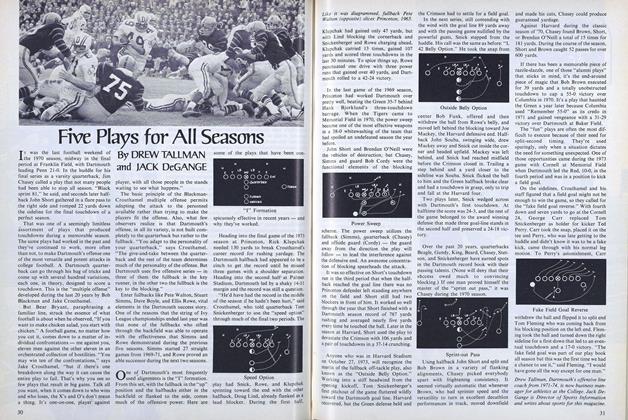

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trials of Reggie

September 1975 By JACK DEGANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

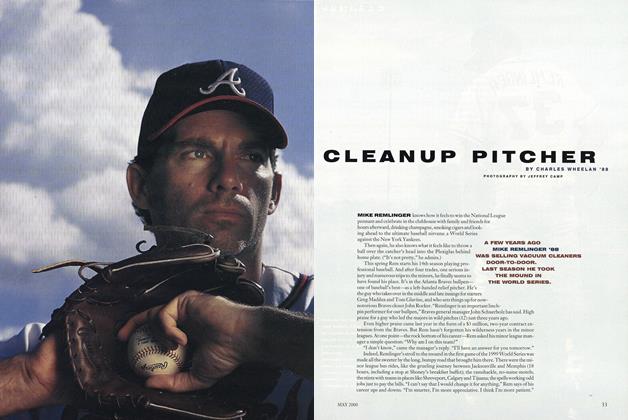

FeatureCleanup Pitcher

MAY 2000 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

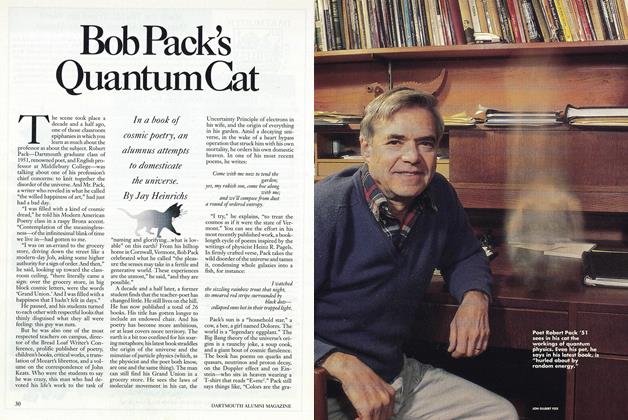

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYWhat’s Going On Here?

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Feature

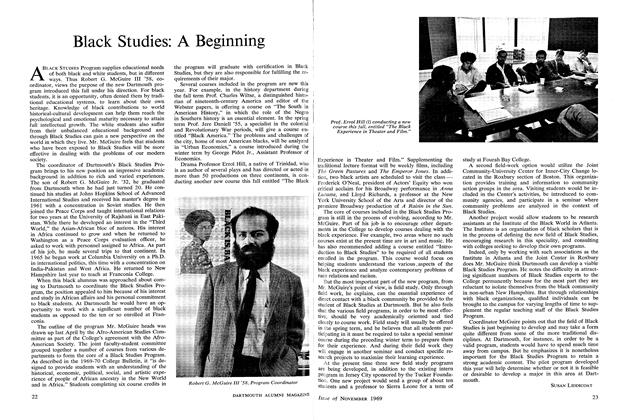

FeatureBlack Studies: A Beginning

NOVEMBER 1969 By SUSAN LIDDICOAT