CHARLIE HALL, just back from two weeks of vacation in the Far East, had flown in from the West Coast. Stan Springer, a one-time assistant to Otto Graham at the Coast Guard Academy and the Washington Redskins, had set some sort of speed record from Trumansburg, New York, to Hanover. Carroll Huntress, who was last at Dartmouth in 1965 as head coach at Bucknell and walked away muttering something about Gene Ryzewicz (who moments before had snaked through assorted obstacles on a 66-yard punt return that produced a scrimmage win over the Bisons), had hustled up from New York.

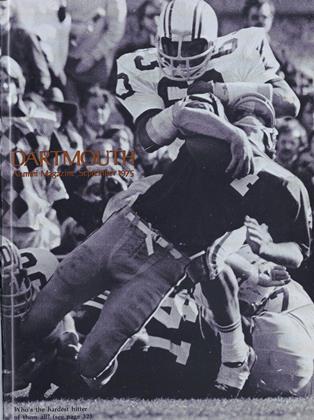

Armed with tape measures, stop watches, and eyes looking for the little things that help in such evaluations, this trio plus a couple of other visitors convened with common purpose along a 40-yard strip of the Leverone Field House track on a sultry Monday afternoon in mid-August. Their business, if we haven't built the picture accurately, is scouting potential pro football players. They represent more than half of the teams in the National Football League, and they arrived in a bunch after Jake Crouthamel dropped a note to Pete Rozelle, the NFL commissioner, and advised that any team wishing to weigh, measure, and time Reggie Williams should plan to do it in a bunch.

Crouthamel, who has built Dartmouth's defense around the Ivy League's premier middle linebacker for the past two seasons, didn't want to take a chance on having his co-captain pull a muscle while accommodating these visitors who otherwise would straggle into town on their own schedule. "That happened to a tackle from Texas a couple of years ago," said Dartmouth's coach, "and the guy missed three games. Why risk it, and why bother Reggie?"

That's how Reggie Williams Day came to be at Dartmouth. What the visitors saw was the man who has over the past two years established himself as probably the finest player at his position that the crusty old Ivy League has ever seen. He ran the 40 four times. The first two clockings were 4.6 and 4.59 seconds. "I put the watch to about 200 college players every year," said Hall. "A lot of them say they can do the 40 in 4.4 or 4.5, but I don't see more than a dozen in the bunch, including the running backs, who can actually run a consistent 4.6."

When it was over, Reggie said he had been a bit stiff (he had been down the road the night before to watch the Giants and Patriots open the NFL exhibition season) while running a shade under 4.8 for the last two pieces. "I wouldn't spend five seconds worrying about your speed," said Springer who then determined that the imposing senior from Flint, Michigan, had lost a pound (to 214) and stretched a quarterinch (to 6 feet, 5/8 inch) since being checked by Hall before the time trial.

On paper, those measurements don't appear unusual. In the flesh, Mr. Williams is something else. Asked who he feels is the hardest hitter on this Dartmouth team, he'll tell you without hesitation and without sounding cocky, "I am, but Skip [Cummins, the rover back] and Kevin [Young, another linebacker] aren't far behind." This threesome, but especially Reggie, provides the reason why Dartmouth's defense should be the best in the Ivy this fall.

In a season where the distribution of talent around the league appears once again to be pretty evenly balanced, Reggie and his mates provide Crouthamel with a defensive full house to make life interesting while things on offense are sorted out. It was the defense that kept things close a year ago, though not quite close enough for the attack to capitalize sufficiently, and it could be more of the same this fall - at least until the appearance of backfield speed (conspicuously missing a year ago), a solid fullback, a tight end, and some speed to go with size in the offensive line.

In the meantime, the focus will be on Reggie Williams. Picked on two preseason All-America teams, he spent the summer term on campus after studying in California during the spring. A psychology major, he's using the Dartmouth football team as a case study in group dynamics and is clearly conscious of leadership value that he and Tom Parnon, the offensive tackle and co-captain, can impart on this team.

Reggie helped make the summer term a useful time frame for more than two dozen players who also were on campus. One of his courses was a drama class that involved a good deal of ballet. He arranged with the instructor to conduct a special weekly session for interested squad members, not only for the exercise and coordination development but because it was a good opportunity to get the players together regularly. It worked out nicely.

"This team is anxious and relaxed," said the man who made every All-East, All-Ivy and All-New England team that was picked last fall as well as an honorable mention All-America. "There's no tension, no feeling of pressure among individuals who will be going against each other for a starting job. The major issue is to win as a team. We have a strong senior class, and during the past two years we've learned a lesson that no other team in the Ivy League can share.

"No one else in the league knows what it feels like to be part of five straight championship seasons. And they don't know what it feels like to have won a championship and then have it all turned around the way things went for us last year [3-6 and the first visit to the Ivy's second division since 1968]. We .have a vivid vision of victory and an equal vision of defeat and we know the consequences of both. This will be a tremendously emotional season. Physically, we have good material but so does everyone else. Teams are going to pound each other for three periods, but it will be the fourth period that tells the story. This is going to be the year of the fourth quarter."

Nor is it likely to be a two-part season - two non-Ivy games and then the league schedule. In 1973 and 1974, Dartmouth lost non-league openers to New Hampshire and Massachusetts (neither had beaten the Green in more than 70 years of trying), and Holy Cross has left Dartmouth's attack in a purple haze for the past two years. In 1973, after losing the first three, Dartmouth came back with six wins and an Ivy title. Last fall, things never fell into place. "This season starts with the first game," said Williams.

The schedule itself presents some strategical assets and liabilities. The opener is at Massachusetts. Then the Green is home for three weeks against Holy Cross, Penn, and Brown. Four of the last five will be at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, and Princeton, with Cornell's mid- November visit to Memorial Field prefacing the finale at Palmer Stadium. The strongest team on the schedule may prove to be Holy Cross, a seasoned collection that has allowed Dartmouth to score the massive sum of three points during the last two engagements.

Around the league, everyone has strengths and weaknesses that require resolution. If Dartmouth's measured strength is Reggie Williams, the offsetting asset in Brown's bag is Bob Bateman, the transfer quarterback from Vermont (which dropped football) who also has been picked to a couple of the speculation All- America teams. Bateman is a reason why some folks have gone so far afield as to tag Brown as the favorite in the Ivy League race this fall. The same people expect Dartmouth to be somewhere in the middle.

That matchup - Williams vs. Bateman - is also the reason that Charlie Hall, Stan Springer, and Carroll Huntress are already joining the scramble for rooms at the Hanover Inn for the weekend of October 18. When was the last time that Brown-Dartmouth, or for that matter, Brown against anyone, shaped up as the highlight of the football season?

The schedule:

Sept. 27 at Massachusetts; Oct. 4 Holy Cross; Oct. 11 Pennsylvania; Oct. 18 Brown; Oct. 25 at Harvard; Nov. 1 at Yale; Nov. 8 at Columbia; Nov. 15 Cornell; Nov. 22 at Princeton.

SUMMER SCENE

This may not be exactly cricket, but it seems there's an unwritten rule of the road in European boat racing, other than those events at the world championship level and Henley, that American oarsmen are finally recognizing. Because so many races are scheduled during an afternoon, it's virtually impossible for officials to recall an event because of a false start - at least not if they hope to stick anywhere near the intended schedule.

As a result, while most American crews are poised for the final command, "ROW!" the craftier European oarsmen try to anticipate the order and frequently are in motion ahead of the more conservative crews. Such was the case when Dartmouth's lightweights, racing against crews from England and West Germany in a regatta at Nottingham a week before the grand venture at Henley, found themselves nearly a length behind before they'd taken a stroke.

Well, it really didn't matter because there was another crew in the two races that Dartmouth rowed at Nottingham - Harvard's lightweights, the only college crew that Dartmouth had been unable to beat during the spring. Whatever the result against the Europeans, it was incidental to the performance against the Crimson. The fundamental objective for Dartmouth at Nottingham was to beat Harvard. It hasn't been Dartmouth's lot to get the upper hand on the Johns too often in recent years (in any sport).

In the late-June prelude to Henley, and rowing on the same man-made course carved from the English countryside where Dartmouth coach Peter Gardner would direct the U.S. national lightweight crew in the world championships in late August, Mike Winer and his lightweight confreres paid little mind to anyone save Harvard. The outcome was perhaps more predictable after the Crimson visited Dartmouth's Connecticut River course for some mid-June training and lost three of four 1,000-meter practice sprints to the Green.

At Nottingham, Dartmouth didn't beat Harvard once but twice. In both races, the crews were virtually even after 1,500 meters, and Dartmouth pulled away in the final sprint to lead the Crimson by nearly two seconds.' The West Germans and British nationals won the races but that was incidental.

A trip that included a memorable visit to Dartmouth, England, and races against that town's amateur oarsmen ended at Henley. Competing for the Thames Challenge Cup, the event for eights that is second only to the Grand Challenge Cup, Dartmouth was pitted in its opening race against one of the home forces, the Henley Boat Club. The Thames Cup is the event that American lightweights normally enter, but Dartmouth was thrown a curve this time.

Henley, averaging 27 (that's no typo) pounds heavier per man, charged to a half- length lead off the start; with less than 500 meters to go the race was dead-even. Dartmouth challenged repeatedly in the final sprint, but lost by barely a second to a crew that rowed the second fastest time of the day. It was a proud performance, typical of a crew that progressed consistently in its development. While competition became a memory, a special tribute remained: the Dartmouth oarsmen were honored by selection as the crew to pass among the congregation to take the collection at church services conducted prior to the championship races at Henley.

For all but one, the season ended for Dartmouth at Henley. Charlie Hoffmann, now a senior, earned a seat in the national lightweight eight and made the return to Nottingham with Gardner for the world championship regatta.

Scene: "Reggie Williams Day." Place: Leverone Field House. Time: 4.59 seconds.

Williams displays a well-turned figure on the training tableand on the boards. He persuaded fellow defenders Skip Cummins and Leroy Goodwine, shown with him and their instructor in the foreground, to tune up in a dance class this summer.

Williams displays a well-turned figure on the training tableand on the boards. He persuaded fellow defenders Skip Cummins and Leroy Goodwine, shown with him and their instructor in the foreground, to tune up in a dance class this summer.

With practiced skill the lightweights toast the Dartmouth Amateur Rowing Club.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52 -

Feature

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureFive Plays for All Seasons

September 1975 By DREW TALLMAN and JACK DeGANGE -

Feature

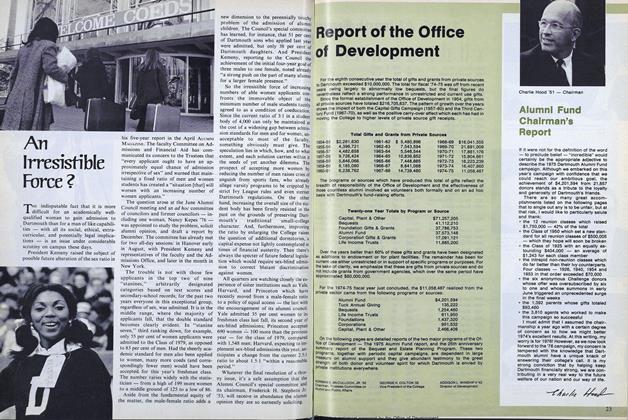

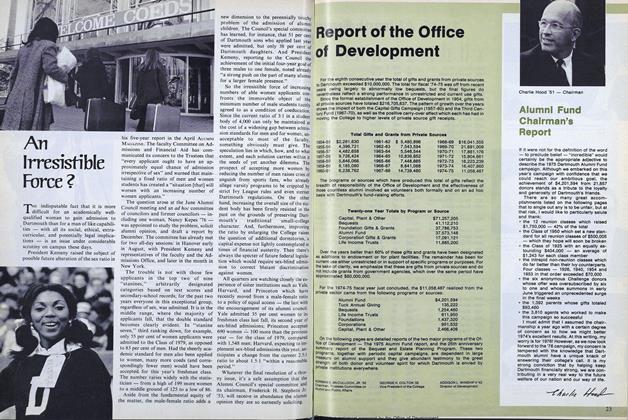

FeatureAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureAn Irresistible Force?

September 1975 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975