A survey of black attitudes toward Dartmouth

TODAY apparently cool, collected black Dartmouth students are found studying in Baker Library, discussing theoretical and practical issues in their rooms or at the Afro-Am center, and generally, deliberately "taking care of business." What a contrast to the late 1960s and early 19705, that thunderous period of civil rights, student activism, and anti-war movements so remote to us now. Yet it was only then that Dartmouth admitted a significant (read: not token) number of black students, many of whom did not exactly fit traditional admissions criteria. The College and many of those young men were not prepared for each other. Although the black students here did not resort to arms like some of their brothers at Sister Cornell, they did find it expedient to separate themselves - in Cutter Hall - from the Dartmouth community.

The tension remained even after they negotiated with the administration in their Cutter Hall redoubt - especially after they emerged from Cutter. And it continues today and will continue until more black students are admitted, more black faculty are recruited, and more black administrators and staff are hired. Yet these gains alone can only promote black-white detente until black students feel that their own socio-cultural symbols are normal at Dartmouth. Even then, some tension will remain because of particular events and circumstances at Dartmouth, and because Dartmouth is a microcosm of the general American society, where the racial scene has always been tense. Sometimes quiet, but always tense.

Activism has two edges. One is sharp, the cutting edge of overt militant action; the other blunt, the theory of militant action. Either can inflict a serious wound. The sharp blow of black activism in the late '6os temporarily stunned the Dartmouth community, as did anti-war activism. The College responded quickly and positively to most of the black students' demands, including the decision to admit around 100 black students yearly, the establishment of the Afro-American center, and the creation of the Black Studies Program. Because of its quick and positive response Dartmouth was in short order able to return to its purpose of providing quality education. Better trained students are less likely (but not always) to be "sharp-edged" activists and, moreover, activism is now passe almost everywhere - in and out of universities. The net result has been a decline of overt activism centered around Cutter Hall and an increase in "dull-edged" militancy amid the stacks of Baker Library.

The resolve of today's black students to eliminate oppression and enhance black dignity is, seemingly, as strong as it was among their counterparts of the recent past. But today's methods differ because the circumstances have changed: the College is now fully committed to "equal opportunity."

Try to picture the complex interconnections between these old and new factors. They add confusion to a milieu where competition is the name of the game. Since competition and institutions tend to mold or reproduce products like themselves, black Dartmouth students are now tending to reflect competitive middle-class backgrounds and traditional achievement criteria. And utilizing the traditional Dartmouth competitive system to attain their goals leaves little time for group isolation in Cutter Hall because it requires too much individual seclusion in Baker Library.

DATA I have been collecting over the past three years illustrate the changing status of black students. These figures tell us a great deal about changing backgrounds: in 1973, slightly more than 19 per cent attended private secondary schools, while better than 22 per cent did so in 1974. In 1975 the figure was over 25 per cent. In 1973 about 53 per cent came from high schools where the great majority of the students were white. The figure reached 59 per cent in 1974, and last year it rose to 65 per cent. Black students coming from predominantly white neighborhoods increased from about 21 per cent to more than 31 per cent in the same three-year period. The data also suggest a significant increase each year in the percentage whose total parental income exceeded $15,000.

But black is not white and the concerns of dull-edged militancy - evident in a report by black students accusing the College of institutional racism and a controversy over maintaining Cutter Hall as an Afro-American cultural center - persist.

At his inauguration in 1970 President Kemeny stated, "We must somehow find the means whereby every student, no matter what social background he comes from, once he is a student at Dartmouth, feels he is a full member of the entire community." Feeling that one is part of the entire community involves many factors ranging from specific aspects of the Dartmouth experience to extracurricular activities in and around the College. In our surveys we asked how socially satisfying black students found the Dartmouth-Hanover community. Only a few found it satisfying, with "bearable" and "unsatisfying" comprising the bulk of the responses. However, they found the New England community, outside Dartmouth-Hanover, significantly more appealing - implying road-tripping to other New England colleges, especially all-female ones. There also was a consistent decline in dissatisfaction with Dartmouth-Hanover as the percentage of female black students increased at Dartmouth - from about 17 per cent in 1973 to slightly more than 30 per cent in 1975.

Fully three-quarters of the black students who participated in our surveys indicated that they were engaged in fewer extracurricular activities than in high school. That could mean they don't like what Dartmouth has to offer or, more likely, that they are bending to the rigors of studies.

What is known for certain is that the Afro-American Society, a center of blackness in a generally white community, fills important needs. Last year all but 15 per cent of the black students at Dartmouth were members, and most of them regularly attended meetings and social events at Cutter Hall. The students felt that one of its main purposes was to promote black culture in the Dartmouth community, and in a related factor fully 80 per cent said it was either essential or desirable to have an all-black dormitory.

In general, black students are rather ingroup oriented with respect to their social lives. This orientation undoubtedly stems from internal as well as external factors. Internally, black peer pressure, like white peer pressure, tends to inhibit those students who under normal circumstances would not oppose socializing with their fellow white students. Consider the following question: "What percentage of your friends at Dartmouth are black?" About two-thirds of the black students tend to socialize among themselves. But a shift seems to be developing. "What policies should there be regarding white student attendance at black activities and programs sponsored by the Afro-American Society?" Only a handful of the blacks indicated that whites should never be allowed to attend activities sponsored by the Afro-American Society, while about three-fourths indicated that whites should be allowed to attend all or most activities. In the 1975 survey none of the respondents indicated that Afro-Am activities should be totally off limits to whites. Such a shift could be - we see this as a possibility rather than a firm conclusion - that the society has become somewhat venerable with time and that it has become easier for black students to feel comfortable there both with themselves and with others.

Is the Afro-American center a source of satisfaction as well as participation? If so, does that satisfaction make up for the dissatisfaction with the general community noted above? Might it even be the case that black students like being at Dartmouth, perhaps thanks to the Afro-American Society, even though they feel isolated from the larger community? Conjecture, possibility, and question - for now we need the passage of more time, and further research, to get any firm answers.

THE focus of blackness does not end at the Afro-American Society. On the average around three-quarters of the black students have taken courses from black faculty members. The figure is remarkable because there are so few blacks on the faculty and because many respondents were just in their first year or two here. Fully 80 per cent of the students have taken black-oriented courses, with most of them saying that such courses should become permanent departmental offerings regardless of whether they were taught by black or white professors. Last year only about a third of the students gave high marks to the present organization of the Black Studies Program. And yet they indicated overwhelmingly that the program should be retained. It seems clear that despite specific complaints, black students want to maintain an emphasis on the relevance of the black experience in their education, as well as in their own intellectual and personal development.

A side issue of the low rating given the Black Studies Program is that significant numbers of white students fail to elect the course offerings. One can argue that important as the program might be for black students, it is even more essential for whites, many of whom have had little or no contact with the black experience before coming to Dartmouth. In a Tucker Foundation survey of the entire student body, only about 60 per cent of the white students said they had been exposed to minority culture before coming to college, while fully two-thirds had no academic exposure while at Dartmouth. (In the same survey three-quarters of the student body felt the Black Studies Program was desirable and almost 75 per cent of the white students felt that the level of racial interaction at the College was too low.) It is possible, therefore, that a reorganization of the Black Studies Program, especially in the way of enriching its limited curriculum, would make it more attractive and valuable to black and white alike.

"Does the Dartmouth administration support institutional racism?" We sought responses to this question using four variables: suppression of cultural identity; employment of black faculty and administrators who exemplify white, middle-class norms; encouraging black students to accept white, middle-class norms; and phasing out and cutting out financial aid. (Financial aid, a complicated subject at best, has hardly been "cut out." The point is that some of the black students perceive that Dartmouth's policies are weighted against them.) Of course, this is just one set of variables indicating what students may feel as manifestations of institutional racism. Incomplete as the list may be, we noted that the complaint level was higher in 1975 than it was earlier.

More often last year than before, black students felt that the institution was attempting to mold them to fit the institution's notion of what a Dartmouth student ought to be, and they contended that Dartmouth often does not consider their social and cultural origins. About half of the respondents felt that Dartmouth employs blacks who fit traditional white norms. Finally, according to black students, the alleged diminution of financial aid represented another ploy to admit only blacks who can pay their way (and presumably those who can pay will be middle-class blacks). As long as a significant portion of black students feel that Dartmouth exhibits institutional racism, it is reasonable to assume that they will also perceive the Afro-American Society as an important means of coping with an alien, difficult, and sometimes hostile environment.

DESPITE generally negative attitudes regarding many aspects of the Dartmouth community, there is other evidence to suggest that black students regard the College as a positive means to a desired end. Better than half came to Dartmouth because they felt it would aid them in establishing future contacts in their careers and increase their earning potential by providing superior educational opportunities. If they were still in high school and knowing what they now know about Dartmouth, an average of 80 per cent would still definitely consider applying for admission. As far as educational goals are concerned, about a fourth felt that a black college could have satisfied them as well as Dartmouth (just three per cent felt that a black college could have done better). The next question elicited a more precise answer: "Do you regret not having attended a black college?" About four-fifths answered in the negative. Finally, an average of 60 per cent said that after graduation they will have a strong alumni obligation to Dartmouth.

The conflicting data may leave the impression that black students are of two minds regarding aspects of their Dartmouth experience. The impression is correct, not because black Dartmouth students are schizophrenic but because black is not white - meaning that Dartmouth's 200-year history does not exactly mirror the black experience in America. Black students may be equated to guests who are graciously welcomed by their hosts and admonished to feel at home, but no matter how effusive the welcome or how gracious the hosts, they feel that they are not members of the family. The College's commitment to equal opportunity has gone a long way to make black students feel at home, and it regards this commitment as giving them the key to the house. But until the College also makes a commitment to promote the black experience, black students will not feel that the Dartmouth experience adequately reflects their reality.

IN sum, black students' attitudes and behavior are often reactions to the College's hesitant and unsure posture regarding the 'black experience. The College is primarily concerned with continuing its tradition of providing quality (white) education and fears that black students may not find that their primary goal. Black students want quality education, but they are concerned that unless or until the College considers significantly expanding its commitment to include the black experience, their presence at Dartmouth will be no different than the state of affairs between blacks and whites in the general society.

Activism has two cutting edges, and both can inflict serious wounds.

The rise in female black students has caused a Jail in the dissatisfaction level.

To many of the blackstudents the Collegeseems hesitant andunsure. Many of thewhites think the levelof racial interaction istoo low.

This article concludes a three-part serieson the black experience at Dartmouth inrecent times. Preceding articles were"Black in the White Academy" by WarnerTraynham '57 (May 1975) and "Before theRevolution" by Albert Moncure '69 andRonald Neale '69 (October 1975).Raymond Hall is assistant professor ofsociology and teaches courses in socialmovements, collective behavior, and urbansociology. He joined the Dartmouthfaculty in 1972. His survey of blackstudents' attitudes was conducted over theyears 1973-75, and the data is part of Project IMPRESS at the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWORDS AND PICTURES MARRIED The Beginnings of DR.SEUSS

April 1976 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureLap After Grim Lap, Note After Sparkling Note

April 1976 By DAVID M. SHRIBMAN '76 -

Feature

FeatureTHE 18th century highboys of Benjamin Randolph's

April 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

April 1976 By GILBERT F. PALMER IV, FREDERICK H. WADDELL -

Article

ArticleVox Clamantis et Clamantis; or College Bites Man

April 1976 By TERENCE R. PARKINSON '71 -

Article

ArticleIn Defense of Prejudice

April 1976 By DAN NELSON '75

Features

-

Feature

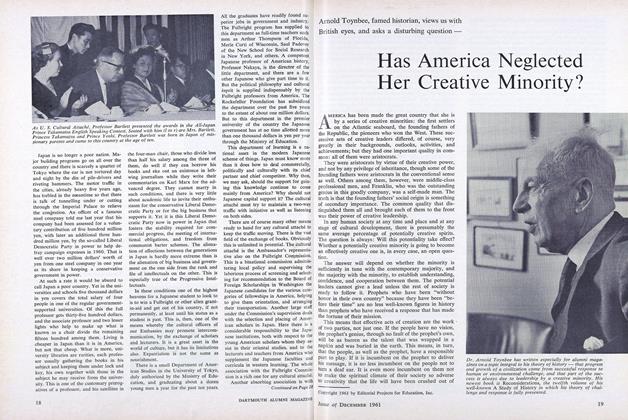

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Feature

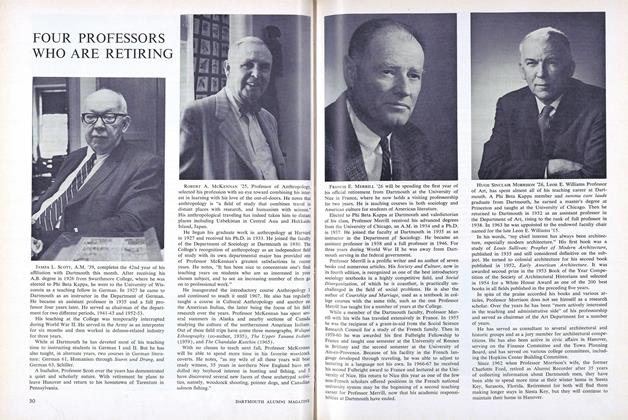

FeatureFOUR PROFESSORS WHO ARE RETIRING

JUNE 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56 -

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

JULY 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14