Incident: "Well, the annual report's gone to the printer, so we're all set. You'll need to know about the stockholder nuts and I'll get to that. The president's people will run the meeting but we'll handle the distribution of the reports, making sure everyone gets one. That's what the stockholders will want to know about. It backs up what the president will say about this year's dividend and how the year ahead looks. That's what they really care about. Everyone of us in public relations will be at the meeting — yes, you, too, new as you are. It's been a crazy week, work every night. The president himself wrote one page of the report, and when he saw it the next morning he wanted to know where that mess had come from. But the report's all done now. The other important thing was the news release. It's on its way to the financial editors at the Times, the Wall Street Journal, the wire services, the papers in Washington. So, we're in good shape. Oh, yes. The stockholder nuts. They come every time, they heckle, they rile the officers, they make speeches; a few of the regulars put on their act. There's a pair of brothers, for instance. I guess they own a few shares in hundreds of companies and they go from meeting to meeting sounding off. Then there's a woman writer who considers herself a Wall Street expert. ..."

Incident: Another corporation's annual meeting was going along as planned. Statements, both meaty and concise, revealed the state of business and presented a carefully thought-out view of the future. The chairman ran the meeting in the individual manner that was expected of him: he was terse, his visage stern. But close to the moment the general had intended to close the meeting, yet another stockholder was on his feet. He fumbled his opening words, evidently wondering how to address the chairman most properly. "Mr. General, I mean, Mr. Chairman . . He took a breath, abruptly disposed of protocol and blurted: "Just how many shares in this company do you own?" The atmosphere of the meeting room instantly became as supercharged as the interior of a thunderhead. The chairman, hawk nose and forehead glistening, leaned forward, glared at the speaker, looking as if, had he been smoking his famous corn cob, he would have bitten through its stem. In a cobra-fast gesture, he pointed at the questioner and rasped, "That's none of your damned business!"

THESE actual occurrences do not necessarily represent a typical stockholders' annual meeting of years past, yet they do show an attitude not infrequently manifested toward those who invested in the corporations. Now it is evident that a dramatic change, even a reversal, has taken place. The big switch in the corporations' attitude toward stockholders was part of the general social upheaval of the '6os. It takes just a series of flash words and phrases to recreate a mental diorama of those years: Parkhurst occupied, hippies evolving into yippies, the Chicago Seven, polarity on campuses from Berkeley to Backwater State. For the '6os, the key word was "protest" but there were others. A couple from Cape Cod attending Alumni College in those years reported, "A student who sat near us kept talking about 'relevance.' Every time a professor said something, the student objected, 'That's not relevant' or asked, 'How is that relevant?' "

But the whole decade wasn't filled with empty, sporadic protest. While we were reading Norman Mailer's black-and-blue prose about the trial in Chicago and the violence at the national political conventions, more soberly organized intervention was evolving. Dartmouth became involved in a case in upstate New York. At Rochester, a civil rights group, organized under the name FIGHT, accused Eastman Kodak of discrimination in its hiring practices and failure to provide constructive training for minority-group members seeking advancement at Kodak. Dartmouth students were approached by FIGHT, an action which subsequently led to requests for the College itself to take a position on the Kodak-FIGHT confrontation. In April 1967, students from a number of colleges attended the company's annual meeting. Dartmouth's endowment portfolio included a $400,000 investment in the photography company — Dartmouth was involved (another key word of the '60s). The Dartmouth reported that at least five students from Hanover would attempt to "fix the fate" of the Kodak investment, joining "over 2,000 other college students from all over the East in travelling to the stockholders' meeting of the Eastman Kodak Company in Flemington, N.J."

The five Dartmouth students did go to Flemington but were not allowed to attend the meeting itself. One of them, Paul F. Stetzer '67, who held a proxy on 30 shares of Kodak stock, was shown into a room where he viewed the meeting via closed-circuit television. According to The Dartmouth, the Kodak meeting was characterized by strong language from FIGHT and apologies and explanations from Kodak. It ended with the controversy unsettled, following bitter words between management and FIGHT.

Another corporate controversy, one that became known as "Campaign GM," involved Dartmouth in 1970. Professor Wayne G. Broehl Jr. of Tuck School, whose "Business Environments" course takes up the growing responsibilities facing companies and their leaders, has termed this dispute, initiated by a Ralph Nader organization, an attempt to force General Motors to broaden its methods of choosing directors. The Nader group — the Project for Corporate Responsibility — went to colleges around the country hopeful of persuading their trustees to vote with it on the issue.

The environmental studies division of the DOC, among other Dartmouth groups, was interested in this issue and pressed the College for a statement defining its attitude toward Campaign GM. Discussions in Hanover followed and a College news release stated, "While urging increased corporate concern for the social problems of the nation, the executive committee of the Trustees of Dartmouth College voted today that its proxy support should go to the board of directors of General Motors Corporation. . .The College had 26,859 shares of GM at that time. The authorization was sent by Dudley W. Orr '29, chairman of the Trustee executive committee. His statement also included the following: The Trustees of Dartmouth College believe that the solution of the social and economic problems of the present day calls for affirmative participation by all segments of American society, including especially the major business corporations. Without such affirmative participation American corporations will not be able to prosper and grow and, over the long term, be profitable investments for their stockholders.

The automobile industry in particular, we feel, has a special responsibility to assume a leadership role because of its involvement with the very acute problems of pollution, safety, and employment of disadvantaged minority groups, as well as because of its economic preeminence. All automobile manufacturers have a tremendous incentive to respond to the public interest and, in our view, the stock of any company whose response is not adequate will not be a worthwhile investment.

Following the Kodak-FIGHT and Campaign GM, the College administration issued a public statement noting the Trustees' responsibility for administering the College's investments. It also noted that information about the College's holdings was available at the treasurer's office and acknowledged that an interchange of ideas based on factual information was a valuable part of the Dartmouth experience.

Among the results of the Kodak controversy and the other early proxy advocacy cases was a heightened awareness of the constructive clout of Dartmouth's portfolio. More immediately, Harvard and Yale had also been experiencing an emergence of student/faculty desire for their institutions to influence the actions of the corporations in which they held shares. Communication followed among the business administration and other experts at Yale, Harvard, Dartmouth, and a few other colleges and universities. Dartmouth's response was to establish an interim committee to help guide the College in influencing, through its stocks, bonds, and mortgages — currently valued at $160 million-plus — the country's largest corporations whose activities have a direct bearing on our way of life. Its name was the Ad Hoc Committee on Investment Objectives.

The committee held a number of public meetings in its first year but the attendance was light, according to Professor Broehl, its chairman, and "interest in the issues seemed to have generally subsided around the campus." Despite that, and the opinion of some critics who found the committee too conservative, the Ad Hoc Committee evolved into the College's Advisory Committee on Investment Objectives, now in- cluding students, faculty, alumni, and administrators.

The present committee, enlarged from its original seven members to ten, as recommended in its 1974-75 annual report, includes the following in addition to Wayne Broehl: alumni members Arthur E. Allen Jr. '32, current chairman; Harry B. Gilmore '34, and James M. Wechsler '55; administration member Marilyn A. Baldwin, assistant vice president; Professors Noel Perrin of the English Department and Charles T. Wood of the History Department; and student members Robin L. Carpenter '66 Tuck '77, Wayne B. Gray 77, and Tayloe Holton '78. All were appointed by President Kemeny.

As their work progressed, committee members were faced with a stupendous amount of homework. Their counterparts in other educational institutions faced the identical problem. The solution was the formation in Washington of the Investor Responsibility Research Center, whose staff lawyers provide Dartmouth and other member institutions with the raw material for making their decisions. Dartmouth vice president John Meek '33, one of the founders of IRRC, remains one of its directors. A variety of organizations throughout the world now purchase IRRC services.

The committee's guidelines for operation, first issued in October 1972 and revised in February 1975, stipulate that it communicate with the Trustees' subcommittee on investment objectives, making specific policy recommendations and annual reports, and keep the subcommittee advised on corporate matters related to the environment and natural resources, equal employment opportunity, consumer protection, and product purity. The committee is also empowered to send letters to corporations, explaining the College's views on certain issues.

Additional operational guidelines regarding general policies and internal principles center on use of the College's land holdings; committee members attendance or non-attendance at corporate meetings; consultation with like-minded institutions; the committee's maintenance of an independent relationship with all professional "advocacy" groups in the field of corporate responsibility.

The guidelines further stipulate that the committee's role is that of a fact-finding and issue-analyzing organ of the Board of Trustees. The committee may hold public hearings on campus if warranted, but will not in any way be a public advocate of any position, for this remains the prerogative of the Board of Trustees.

Thus, for four years now, the committee has been carefully examining corporate policies affecting the use of energy, political contributions, preservation or reconstruction of the environment, equal employment opportunity and practices, and other socio-economic factors in our daily living.

SOUTH Africa and its problems have figured in the committee's work from its beginning. A group organized as the Church Project on U.S. Investments proposed disclosure of corporate activity in South Africa on the part of Eastman Kodak, GE, IBM, and Xerox. The committee recommended voting in favor of the proposal and against management.

In another instance, IBM shareholders, including the Church Project, repeated a request for a variety of information about IBM's business in South Africa. The particular proposal was interpreted by the committee as an effort to prevent IBM from doing business in South Africa. Since this involved foreign policy which the committee recognized as within the sole jurisdiction of the U.S. Government, it "could not support this proposal." It was recommended that the Trustees favor management in this case.

Equal employment has been another area of committee study. At one time the College owned stock in five corporations whose shareholders had been asked to vote on disclosure of information on equal employment. The corporations were Ford, GE, GM, Gulf Oil, and IBM. Data covering three years regarding race, sex, and job category were among the facts wanted. The committee recommended voting yes for the proposal (thus against manage- ment).

Another matter of general concern, the Arab boycott, was taken up. A number of corporations, including Exxon and Gulf Oil, were presented with a resolution by the American Jewish Congress, which the committee felt was badly drawn and which, additionally, asked for some information that could not feasibly be released. Here, the committee recommended support of management. Subsequently, the American Jewish Congress apparently agreed and drafted a new resolution for later presentation.

Wayne Broehl emphasizes the complexity and diversity of the committee's meetings, pointing out that they are devoid of block voting, with the members usually taking different tacks regarding the varied issues studied. Broehl also stresses the need to establish a certain directness. He cites the B-1 bomber controversy — the national debate over whether the Defense Department should proceed with a multi-billion-dollar program for a new supersonic bomber to replace the B-52 — coincidentally noting that it serves as example of the committee's voting with management. (The committee may vote pro, con, or abstain.) Broehl explains that in this case of voting with GE management (GE was chosen as manufacturer of the B-1's engines), the committee was not the B-l bomber program. It was voting in favor of having the federal government make a decision regarding the production of the big aircraft, but not allowing an advocacy group to squelch obliquely the bomber program by singling out a major component manufacturer for attack.

Exemplifying the committee's fairly frequent decisions to abstain in a proxy vote is a case involving Merck & Company. "Unusual payments overseas" was the subject of a resolution sent Merck by the United Church Board for World Ministries. While sympathetic with the intent, the committee found some of the resolution's wording imprecise, particularly in such phrases as "purchase favor for its own operations" and "to aid anyone to obtain or retain governmental powers."

On May 4 of this year F. William Andres '29, chairman of the Board of Trustees, wrote Merck that:

The Board has directed me to express our concern about the issue of questionable payments of corporate funds. The college community, along with other institutions in society, has been alarmed by the apparent widespread instances of such payments. The solutions to these inappropriate corporate practices must in the final analysis lie with the corporation's own governance system — its board of directors and management, in some cases additionally constrained by federal or state law enforcement agencies. While the university communities around the country do not take a direct role in this, we as the Dartmouth Board of Trustees wish to urge you to take all necessary actions to fully determine the past slippages in the system and to develop internal constraints that will prevent such occurrences from happening in the future. We would welcome an interchange with you concerning this important issue.

The committee often recommends against corporate management policy. The 1975-76 report stated: "AT & T — The ... resolution requested the company to disclose details on political action committees and trustee committees, set up under the law, as well as corporate funds legally expended for political contributions in state and local jurisdictions. It was felt that such information was of legitimate shareholder interest and that provision of it would not be unduly burdensome to the company."

The guidelines for operation of the committee include the statement "... the disposition and use of Dartmouth College landholdings will be considered by the committee in the same light as investments in corporate securities." There is a case as close to the campus as West Corinth, Vermont, where the College's bequest holdings include a once-productive copper mine. A Canadian company wanted to begin reworking the old mine and proposed an arrangement that seemed lucrative to the College. Test drilling indicated that new mining would be worthwhile.

"The question almost immediately came up regarding social implications to the small towns in the area," Broehl recalls. The operation called for strip mining, but after the committee studied the plans and visited the mine site the Canadian company agreed to switch to deep mining instead and to protect the environment of the surrounding community. Eventually, the mine may be re-worked profitably under environmentally acceptable conditions.

The College's intercession on its doorstep in West Corinth symbolizes the way the committee's efforts have caused both those who administer the Dartmouth holdings and corporation executives to become more acutely aware of their responsibilities to all of society.

In 1967, outside President Dickey's office, students raise a question of shortsightedness in Dartmouth's Kodak holdings.

Bliss K. Thome '3B and Nancy Decatowrote about Dr. Peter Hauri's sleep project at the Medical School in the Februaryissue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureHarvard Myths About Dartmouth

September 1976 By ERICH SEGAL -

Feature

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Article

ArticleMeasured Quantities

September 1976 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926's 50th

September 1976 By H. DONALD NORSTRAND

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Feature

FeatureWHY COLLEGE ?

December 1973 -

Cover Story

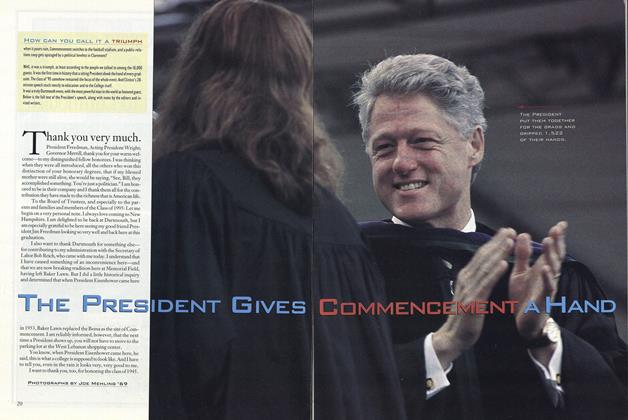

Cover StoryThe President Gives Commencement a Hand

September 1995 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH ALUMNI FUND REPORT

NOVEMBER 1963 By Charles F. Moore, Jr. '25 -

Cover Story

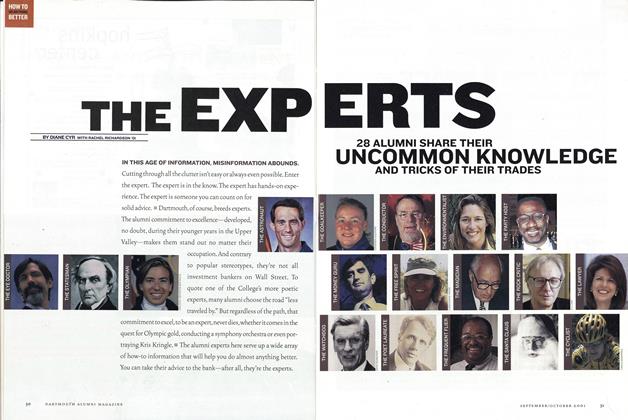

Cover StoryThe Experts

Sept/Oct 2001 By DIANE CYR WITH RACHEL RICHARDSON ’01 -

Feature

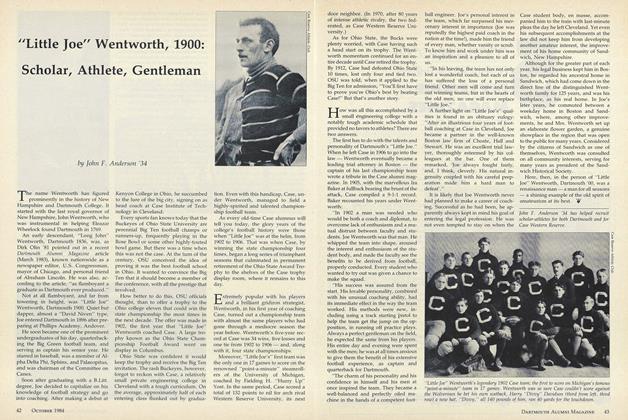

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

OCTOBER 1984 By John F. Anderson '34