This book is not long. It contains fewer than 160 pages, over a third of which are devoted to color photographs. What is large about the book is its ambition: "... we must now more than ever try to understand what wilderness can teach us of life, of balance, of quality, of freedom. It is the hope of this book, its text, its photographs, its purpose, that if we can someday bring ourselves to understand these things, truly understand them, then perhaps we can begin to build a world in which our dreams no longer die."

Understanding of this sort is achieved less by documentation than by suggestion. Jones, who already has earned a solid reputation as a nature photographer, excels in producing pictures of landscapes loved by particular men. His film John Muir's High Sierra was nominated for an academy award; another on Robert Frost has earned high praise; and his photo essay "Look of a Land Beloved," which focused on the rural Vermont and New Hampshire Frost loved, appeared in the April National Geographic.

Predictably, therefore, the photographs in this book are more than just scenic. They are, as the title states, images of John Muir's America, photographs of places he perhaps saw more truly than any other American. They range from the Muir family farm in Montello, Wisconsin, to the California Sierra, to Washington's Mt. Rainier, to Glacier Bay in Alaska. The majority — and the most perceptive — are of Yosemite, the wilderness which John Muir gave to America.

This gift was Muir's greatest. He gave it in two ways: through the waging of conservation battles and, perhaps more important, through the inspiration of this perception of wilderness and his sensitivity to its non-commercial values in an era of single-minded expansion and exploitation. His ambition was"both to share his own experience of wilderness with his contemporaries and to preserve it for future generations.

Although he took up the pen in defense of his particular vision, and although he exerted considerable influence as a writer, Muir recognized the inherent limitations of what he described as his "harsh and gravelly sentences." He protested, "These mountain fires that glow in one's blood are free to all, but I cannot find the chemistry that may press them unimpaired into book-seller's bricks."

This volume, however, is one "book-seller's brick" which somehow conveys a good deal of the "chemistry" of Muir's vision. The secret, one suspects, is in Jones's photography, which sees America in a light close to that in which Muir must have seen it and which allows the reader to be also a seer. These are more than just pretty pictures. As Jones explains, "... photography to me is not an end but a means to an end. The end is life-style, an attitude, an approach to the world that is filled with both reverence and wonder." It shows.

But don't let the pictures, excellent as they are, distract you from the text. Muir himself, the mechanical genius who turned tramp after an eye injury, is too interesting, and co-author T. H. Watkins is too creative. The text divides Muir's life into thirds, sketches in the details, and punctuates the divisions with three "dialogues" which occur between the author and the "ghost" of John Muir. These dialogues, in particular, give the "ghost" substance. By the end of the book the reader has made more than just an aquaintance with John Muir; he has seen some of America as Muir must have.

JOHN MUIR'S AMERICAPhotographs by Dewitt Jones '65Crown, 1976. 159 pp. $18.95

A mountaineer from the Pacific Northwest, Mr.Nelson with this issue becomes an assistanteditor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE IVORY FOXHOLE

October 1976 By JEFFREY HART -

Feature

FeatureMENAGE A HUIT

October 1976 By ROGERS E. M. WHITAKER -

Feature

FeatureRED BALLING IN THE JERSEY NIGHT

October 1976 By Jeffrey Brodrick -

Feature

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL -

Article

Article'My Own House'

October 1976 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

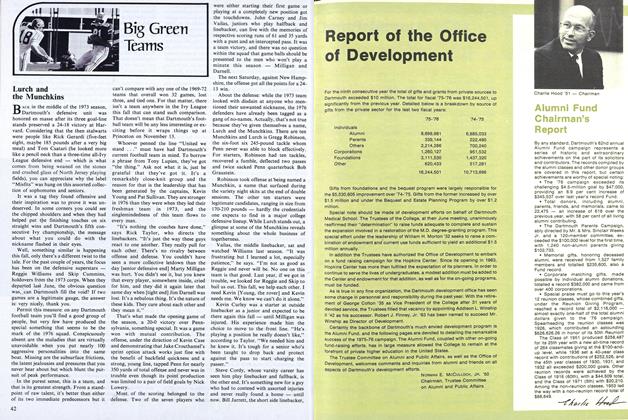

ArticleAlumni Fund Chairman's Report

October 1976

Books

-

Books

BooksThe New England Quarterly

November 1936 -

Books

BooksJuxtapositions

December 1976 -

Books

BooksNERVOUS BREAKDOWNS

December 1933 By C. N. Allen -

Books

BooksCONTRACEPTION AND FERTILITY IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS.

November 1942 By James F. Crow -

Books

BooksINTERNAL STRUCTURE OF GRANITIC PEGMATITES.

December 1949 By Richard E. Stoiber '32 -

Books

BooksAMERICAN LABOR UNIONS; ORGANIZATION, AIMS, AND POWER.

July 1950 By Robert Swanton