HAS Dartmouth succeeded in conserving energy since the energy crisis? According to Richard W. Plummer '54, director of Buildings and Grounds, energy-conserving measures have saved Dartmouth over $800,000, or the equivalent of three million gallons of oil, since the 1973 emergency. Plummer estimates that during the 1975-76 fiscal year alone, savings amounted to $300,000, about 21 per cent of Dartmouth's $1.4 million energy bill.

Initially, Dartmouth's energy savings were due to campus-wide publicity calling for student and staff assistance in reducing the College's energy consumption. Buildings and Grounds even offered a weekly keg to the dorm that conserved the most energy. Following in the wake of the publicity campaign, the College increased insulation in the buildings, decreased the standard room temperature to 65 degrees during the day, and installed sensing devices which regulate dormitory heat according to temperatures inside and outside the buildings.

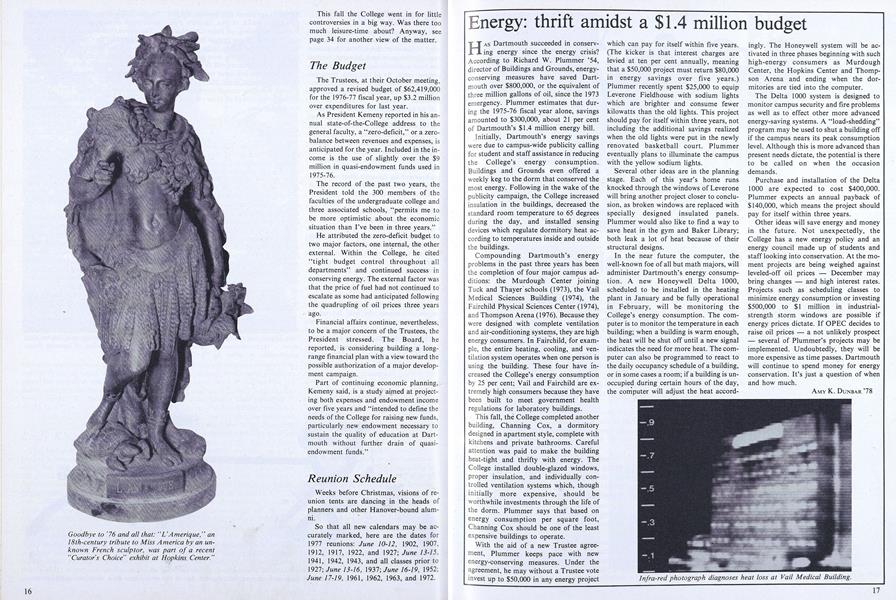

Compounding Dartmouth's energy problems in the past three years has been the completion of four major campus additions: the Murdough Center joining Tuck and Thayer'schools (1973), the Vail Medical Sciences Building (1974), the Fairchild Physical Sciences Center (1974), and Thompson Arena (1976). Because they were designed with complete ventilation and air-conditioning systems, they are high energy consumers. In Fairchild, for example, the entire heating, cooling, and ventilation system operates when one person is using the building. These four have increased the College's energy consumption by 25 per cent; Vail and Fairchild are extremely high consumers because they have been built to meet government health regulations for laboratory buildings.

This fall, the College completed another building, Channing Cox, a dormitory designed in apartment style, complete with kitchens and private bathrooms. Careful attention was paid to make the building heat-tight and thrifty with energy. The College installed double-glazed windows, proper insulation, and individually controlled ventilation systems which, though initially more expensive, should be worthwhile investments through the life of the dorm. Plufnmer says that based on energy consumption per square foot, Channing Cox should be one of the least expensive buildings to operate.

With the aid of a new Trustee agreement, Plummer keeps pace with new energy-conserving measures. Under the agreement, he may without a Trustee vote invest up to $50,000 in any energy project which can pay for itself within five years. (The kicker is that interest charges are levied at ten per cent annually, meaning that a $50,000 project must return $80,000 in energy savings over five years.) Plummer recently spent $25,000 to equip Leverone Fieldhouse with sodium lights which are brighter and consume fewer kilowatts than the old lights. This project should pay for itself within three years, not including the additional savings realized when the old lights were put in the newly renovated basketball court. Plummer eventually plans to illuminate the campus with the yellow sodium lights.

Several other ideas are in the planning stage. Each of this year's home runs knocked through the windows of Leverone will bring another project closer to conclusion, as broken windows are replaced with specially designed insulated panels. Plummer would also like to find a way to save heat in the gym and Baker Library; both leak a lot of heat because of their structural designs.

In the near future the computer, the well-known foe of all but math majors, will administer Dartmouth's energy consumption. A new Honeywell Delta 1000, scheduled to be installed in the heating plant in January and be fully operational in February, will be monitoring the College's energy consumption. The computer is to monitor the temperature in each building; when a building is warm enough, the heat will be shut off until a new signal indicates the need for more heat. The computer can also be programmed to react to the daily occupancy schedule of a building, or in some cases a room; if a building is unoccupied during certain hours of the day, the computer will adjust the heat accordingly. The Honeywell system will be activated in three phases beginning with such high-energy consumers as Murdough Center, the Hopkins Center and Thompson Arena and ending when the dormitories are tied into the computer.

The Delta 1000 system is designed to monitor campus security and fire problems as well as to effect other more advanced energy-saving systems. A "load-shedding" program may be used to shut a building off if the campus nears its peak consumption level. Although this is more advanced than present needs dictate, the potential is there to be called on when the occasion demands.

Purchase and installation of the Delta 1000 are expected to cost $400,000. Plummer expects an annual payback of $140,000, which means the project should pay for itself within three years. Other ideas will save energy and money in the future. Not unexpectedly, the College has a new energy policy and an energy council made up of students and staff looking into conservation. At the moment projects are being weighed against leveled-off oil prices - December may bring changes - and high interest rates. Projects such as scheduling classes to minimize energy consumption or investing $500,000 to $1 million in industrialstrength storm windows are possible if energy prices dictate. If OPEC decides to raise oil prices - a not unlikely prospect - several of Plummer's projects may be implemented. Undoubtedly, they will be more expensive as time passes. Dartmouth will continue to spend money for energy conservation. It's just a question of when and how much.

Infra-red photograph diagnoses heat loss at Vail Medical Building.

Article

-

Article

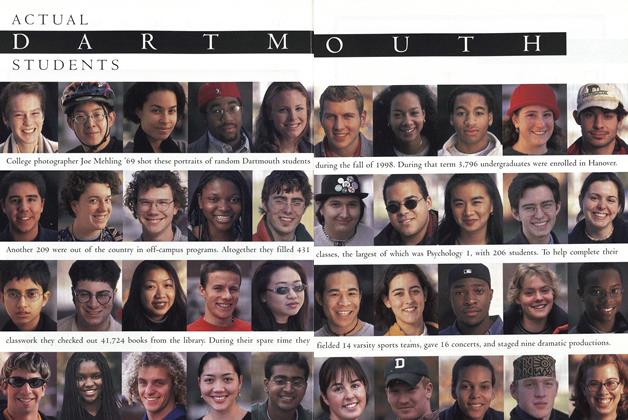

ArticleACTUAL DARTMOUTH STUDENTS

JUNE 1999 -

Article

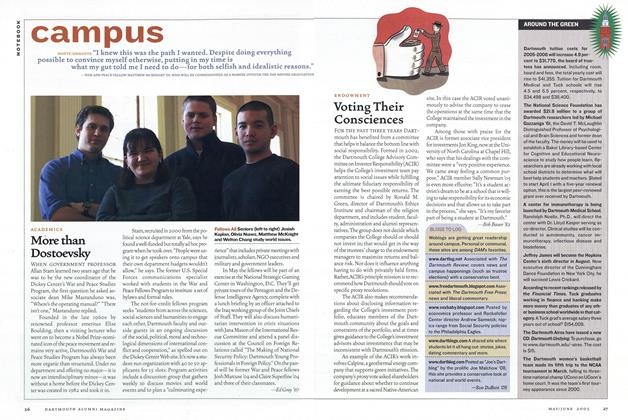

ArticleAROUND THE GREEN

May/June 2005 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth on the Thames

June 1950 By David L. Larson '53 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleSharing Faith and Fear

MAY 1982 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1942 By William P. Kimball '29