EDUCATION, like the other aspects of society, must be continually modified and modernized in order to remain relevant. But the business of modifying and modernizing is a difficult one. One of the primary difficulties is institutional inertia. An organization in one form tends to remain in that form.

Our educational system, Dartmouth included, has not escaped the effects of this institutional inertia. To the contrary, the aura of the "hallowed halls" and the status quo orientation of alumni reinforce the tendency to keep things as they are.

How does organizational change come about? How does an institution, educational or otherwise, begin to move in a new direction? And how does an institution begin to see itself in a new way?

The total answer to these questions, of course, is very involved and complex; but there are some fairly simple steps which can be taken to set at least a few wheels in motion for change. One of these "fairly simple steps," perhaps the simplest, is making a change in the name of the organization - or a part of the organization.

In American society, the question "What's in a name?" has been asked so often that it is now a cliche. But there is often very much in a name. That the name of an organization is indicative of its nature is a notion too obvious to mention.

There are two significant parts to organizational namechanging. First, a name change may simply be more in tune with the true nature of the organization as it already exists. When the ABC Powder Company ceases to produce only gunpowder and begins to manufacture a score of other products, the name is changed to ABC, Inc. Here, the new title simply better reflects the already existing multi-faceted nature of the company. A similar development took place after World War II when the War Department and the Navy Department were merged into the Defense Department. This change involved some fairly substantive alterations in the organization, but basically the word "defense" was perceived to be more in line with the purposes and functions that the nation had for the military.

The second facet, more subtle, and perhaps more important, is the proposition that a change in name can often bring about, or at least help bring about, a change in the nature of the organization. When the ABC Powder Company becomes ABC, Inc., the employees and public begin to think of the organization as a conglomerate corporation. They perceive a different role for the organization. They perceive a different role for themselves, and both the company and its employees begin to function differently.

The same "definitional dynamics" can certainly apply to the organizational structure of an educational institution. Schools are usually organized into administrative staff units and operating departments. To draw again on the workings of corporations, we tend to think of the operating departments that actually produce the product. In education, the product is learning and the departments do the teaching.

Organizationally, this is as it should be. But I think the words we use to describe this component of a school do not accurately reflect its true nature - and certainly not what we hope is its true nature.

My particular concern here centers around the use of the word department. There has been much talk in recent years about the need for an interdisciplinary approach to education, particularly in post-secondary education. Much of the study of political science involves sociology and economics. Much of the study of biology involves chemistry and physics and botany. And so on. The bailiwicks of the various educational departments are very much interrelated. This is a by-word in modern educational philosophy. Yet, in the face of this wisdom, we persist in calling school-teaching units "departments." The prime dictionary definition of "department" is a separate part, division, or branch. . . ." Definitionally then, a department suggests a condition of separateness. In terms of connotations and implications, a department is a compartment with clearly defined boundaries and carrying with it a sense of isolation.

In short, the connotations of "department" run counter to the present trend toward an interdisciplinary approach to education.

In light of this, I am suggesting a neologism: "aspect."

If the goal of education is an understanding of and an ability to live in the world around us, then the study of French or physics or economics is a specific aspect of that larger goal. The word "aspect" suggests a "way of looking at" something. It also suggests exposure to a range of ideas and facts. The mere use of "aspect" would help us to get away from the compartmentalized approach to education. And it would help us to move toward a truly interdisciplinary approach.

If history, for example, is one aspect - one way of looking at the world - then let's talk in terms of the History Aspect, not the History Department. Let's talk about the Physics Aspect, the German Aspect, and the International Relations Aspect.

This simple change - the new use of the word "aspect - could have two fairly substantive effects. First, the new terminology would more accurately reflect edycational trends. In reality, of course, an Aspect would at first be simply a traditional educational department with a new name. But at least the goal of a truly interdisciplinary approach would be reflected in the new appellation. Secondly, as in the previous examples, students and teachers would gradually begin to talk of and think of the organization in a different way.

A change in attitude could eventually produce a change in behavior. And perhaps - just perhaps - a teaching department, for a time only nominally an Aspect, would become a real one.

Stephen Hayes specializes in international economics at theTreasury Department.

Article

-

Article

ArticleNew Hampshire Surgical Club at Dartmouth

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleAbout the Artist

Jan/Feb 2003 -

Article

ArticleA Not-So-Ancient Tradition: The Rag

MARCH 1994 By Ericka F. Houck '93 -

Article

ArticleTHAYER SOCIETY OF ENGINEERS

APRIL, 1927 By F. H. MUNKELT -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

November 1932 By Hap Hinman'10 -

Article

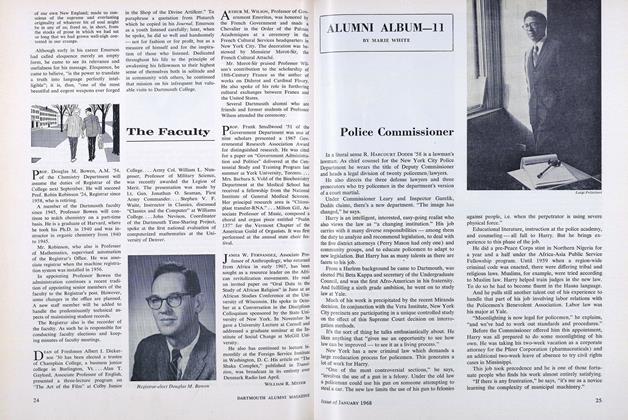

ArticleThe Faculty

JANUARY 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER