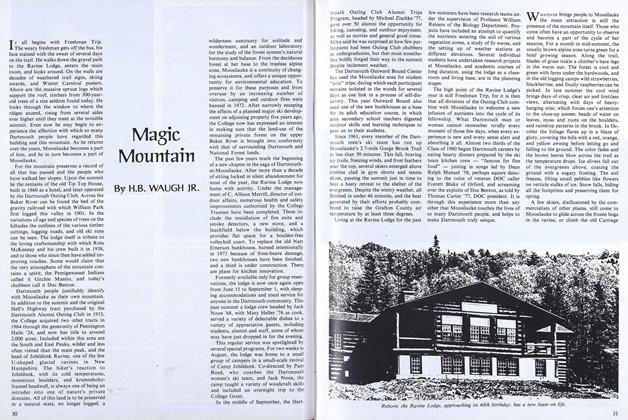

SOME of Dartmouth's best teachers never stand in front of classrooms and never give grades, yet students under their direction spend hours of free time at work. Thanks to President Hopkins, who felt that an education in the liberal arts needed to be complimented by the opportunity to practice the manual arts, there are craftsmen as well as professors on the College payroll. One of them is Walker T. Weed '40, director of the crafts program in the Hopkins Center student workshops since 1964.

Weed is a furniture designer and builder whose work has been exhibited in galleries, museums, and shows in the United States, Europe, and Asia. After graduation from Dartmouth with, of all things, an English major, he went to work in Washington, D.C., as a manufacturer's representative, a job interrupted by wartime service in the 10th Mountain Division. In 1948, he went into business in Gilford, New Hampshire, as a self-employed cabinetmaker, a trade and way of life he has followed ever since.

A self-taught craftsman, with no formal training or family background in carpentry, Weed has been making things with wood for as long as he can remember. "I had my own shop in the house and some power tools," he says. "When I was 12 I made coffee tables and sold them for $5 - to relatives. There wasn't any shop when I was at Dartmouth, but we used to make things in the DOC cabin crew - pretty rough stuff - with axes and buck saws."

The Dartmouth woodshop was established at Hopkins' request in 1941 by Virgil Polling. Located first in the old Bissell hall, it was temporarily dislocated when Bissell was demolished to make room for the Hop. Upon completion of the Hopkins Center, the present shop was outfitted through a donation from the Rockwell Corporation, and metal, jewelry and, most recently, pottery facilities were added.

Colonial, Shaker, and Scandinavian influences are apparent in most of Weed's furniture. He spent a year in Norway with his family studying Scandinavian design and crafts, but doesn't like to pigeon-hole a style, to strictly classify his designs as modern or traditional. "I like to keep my work as simple as possible. It comes from me, a synthesis of things I like." Restraint, even sparseness, of design is complemented by unobtrusive finishes of linseed oil or oil resin, finishes that become a part of the wood and not just painted over it. "Simplicity," according to Weed, "is a great facet of beauty. ... I particularly admire strength of construction achieved with economy of material."

Observing that almost everything in furniture design has already been done at some time or another, he feels that "the extent of a craftsman's originality is in restatement, in selecting materials, in doing things that can't be done in mass production - one-of-a-kind things. It's hard to try to say what you're doing unconsciously. The minute you start to explain you get tripped up. I suppose I like to let beauty speak for itself, to make furniture as close as possible to natural forms the wood originated in."

The Weed's home near Moose Mountain in Etna, New Hampshire, an 18th-century cape with a gray barn containing his workshop, is almost completely furnished by Walker's hands and by the products of his wife Hazel's loom. He built the intricate loom, along with spinning wheels and accessories, from traditional designs. The home and shop are in every way the friendly and familiar environment he finds essential for his work.

Many originals of the designs Weed has sold are here: a rocking chair, a drop-leaf dining table, desks, and one of his favorites, an open hanging chair that was perhaps the most difficult. "Chairs have to fit. They're very personal, not like a chest of drawers." Although he builds furniture to order, he says the things he has made for himself have always turned out the best. "People seem to like them well enough to want for themselves."

Most of his time, however, is spent working with students and supervising operations of the Hopkins Center shops, assisted by Ralph Rogers in the woodshop, "Snip" LaFountain in the metal shop, and Erling Heistad in the jewelry and pottery studios. Nearly one third of the student body, in addition to quite a few faculty and administrative officers, takes advantage of the facilities which are open most afternoons and some evenings. Out-standing student projects have included the manufacture of guitars, flutes, recorders, banjos, and the assembly of harpsichords. Canoes and skiffs have been made, sailboats outfitted, and fiberglass kayaks constructed. Canoe paddles and skis are favorite projects, and so are the in-numerable bookcases, tables, and chairs for dorm rooms.

There have been no serious accidents, a record Weed attributes to intelligent users, lack of boredom, and the required safety classes. There are no credit courses taught in the shops, but the staff is kept busy answering questions and offering asked-for advice. "The problem-solving we do is facinating," Weed says. "One problem after another. It's never boring." The students he enjoys most are "the guys who come in here all thumbs and do something and get excited about it."

There are bound to be some frustrations. Because of the number of people now using the shops, the staff sometimes feels it is only able to offer superficial assistance to any one individual. Weed explains: "You help them through a project, but that's about it. You have to spread yourself too thin. And then to try to help someone in all this noise!" The noise is the worst problem. When the shop is busy with people using power tools, some students just give up and leave. It is difficult to concentrate, difficult to make oneself heard without shouting. Most people wear earguards to protect their hearing.

When asked about the future of fine hand craftsmanship. Weed noted an increase in involvement. As a former council member of the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen and a former trustee of the American Craftsmen's Council, he should know. "There are lots more serious and good craftsmen than there used to be," he says, "but also lots of 'hackers.' I suppose many people start out that way and get better. Today the atmosphere is better than when I started. There are more opportunities to learn."

Asked about plans for future projects, he queried, "Other than my casket, you mean?" He plans to continue teaching, preferring it to the strain of being a fulltime craftsman. "It's a real tough business. You have to dig all the time. The playful things that I have time to do now are really the most fun." The main attraction at Dartmouth for him is the student contact. "Working with students is what makes it all worthwhile."

Walker Weed's hanging chair.

D.M.N.

-

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleClean Sweeper

DEC. 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleSignal-Caller for the Hurt

October 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleBroadway Debut

JAN./FEB. 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleRugby, Mud, and Mardi Gras

May 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

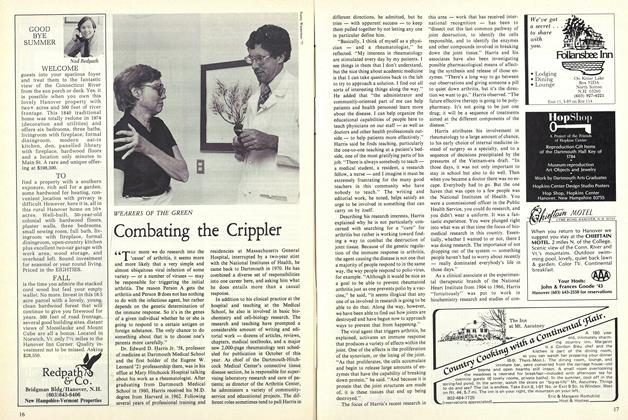

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N.

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' ADDRESS AT COMMENCEMENT VESPERS

June, 1910 -

Article

ArticleNEW FELLOWSHIPS ANNOUNCED FOR GRADUATE STUDY ABROAD

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

June 1946 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

May 1962 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

MAY 1964 -

Article

ArticleSPEECH IN BEHALF OF THE CLASS OF 1911, ON RECEIVING THE SENIOR FENCE

June, 1910 By Harry Butler '11