THE training room at Davis Varsity House is clean, convivial, and crowded. Outside in the lobby, players waiting to be taped lounge on the floor watching a television soap opera. Inside, lined up in the middle of the room, are four examination tables, the kind found in doctors' offices. At the head of each table sits a neatly organized cart loaded with gauze pads, sponges, elastic bandages, tongue depressors, scissors, and several varieties of tape. Beside each table a trainer is working. Fred Kelley, the head trainer, presides over the first table, answering players' questions about sprains, strains, pulled muscles, and bruises while he quickly bandages an assortment of knees, ankles, hands, and every so often a shoulder.

"Hey, Fred. Heat or ice on this one?" "Give it some heat. Then put it in the whirlpool."

It is only the first week of football practice but already Kelley seems to know each player and how he hurt himself. Kelley and his three assistants work with 113 varsity and 90 freshmen players. "Some guys you see a lot," he says, "and some hardly ever come in. But over the course of the season you see almost all of them at some time or another."

"Look at this bruise," someone demands.

"Who were you out with last night?" Kelley asks him.

"I think of players in three categories," he confided later. "You have your normal player who wants to go back into competition as soon as he's recovered from an injury. Then you have your hyper-athlete who's begging to go back too soon, before he's healed. Finally, there is the hypoathlete who's so concerned about being hurt that he holds back. We don't push anyone back out on the field until he's ready."

There are three other, more official, categories for injured players. If someone is severely injured he is out, maybe recuperating at Dick's House. The walking wounded - too badly hurt to play but well enough to come to practice - are given red shirts and told to watch from the sidelines. The willing and able, but less than fully recovered, are given shirts with a green cross meaning they can practice but shouldn't be hit by teammates.

Kelley's responsibilities as head trainer - he's also the varsity baseball coach - include the conditioning of athletes, assisting the team physician, Dr. James Ramsay, in the care and rehabilitation of injuries, and working to prevent injuries. Both Kelley and Ramsay are responsible to the College Health Service, not the athletic department. It is not a common arrangement at other schools, but Kelley, Ramsay, and the coaches agree it goes a long way toward preventing a conflict of interest.

Imagine a situation at the Dartmouth-Harvard game: It's late in the fourth quarter, the score is 7-7, and Dartmouth has the ball deep in Harvard territory. Senior Buddy Teevens, co-captain and quarterback, has been tackled hard throughout the game and is limping. He gets hit again, just below the knees, and needs help getting up. Ramsay and Kelley check him over, confer for a moment, and tell the coach Teevens shouldn't go back in. No argument.

"The decision about whether or not a kid should play is absolutely up to the team physician," Kelley said. "Medical decisions are not questioned. If we ever err at Dartmouth when it comes to injuries, it's on the side of conservatism." Head Football Coach Joe Yukica concurred: "Whatever they say about an injury we're happy to follow."

Kelley is not a doctor (he was in the premed program at Springfield College), but his opinions about injuries are respected by physicians. "Fred's judgment in the handling of injuries is outstanding," Ramsay said. "He even gives lectures on the psychological effects of injuries." Coach Yukica commented that "Kelley has an excellent feel for just how hurt a kid is. He's able to bring an injured player back as soon as possible, but not too soon. The players have confidence in him. He tells them what they'll have to do in order to recover, and if they follow the program, that's just what will happen." Yukica's predecessor, "Jake Crouthamel '6O, now director of athletics at Syracuse University, stated, "His knowledge of practical medicine when it comes to athletic-related injuries is well above that of most people in his profession. I think his competence is demonstrated by how highly regarded he is by the medical staff at Hitchcock and by the fact that he's asked to talk to doctors about injuries."

Kelley's abilities are more than medical, his associates point out. "Along with Fred's competence you have to talk about his way with people," Ramsay noted. "Fred takes every injury very personally," Crouthamel explained. "If a player has a sprained ankle, Fred has a sprained ankle. Every player feels like he's getting Fred's individual attention." Len Nichols '76, a former offensive guard who now serves as a financial aid officer and who helps out coaching the freshman team, told me, "Kelley's the best friend a player can have, in a lot of ways. All the guys I played with liked and respected him."

Kelley doesn't talk for long about football injuries without talking about conditioning. Thinking about a recent SportsIllustrated article about brutality in football, I asked if today's players, bigger now than their fathers were when they played, do more damage to one another. "The athletes are bigger," Kelley agreed, "but they're also better conditioned and have received the benefits of better nutrition. I don't think we've had more injuries recently, although maybe we've had different kinds of injuries. We might be seeing more spinal injuries."

The pre-season conditioning program Kelley prescribes for the team combines weight-training, endurance runs, and wind sprints. The weight program is designed to develop "bulk and explosive power," he explained, and the running improves cardiovascular fitness. Kelley said the players "came back this year in as good or better shape as I've ever seen them." The offfield, in-season conditioning program includes weight-lifting every other day after practice. The athletes use barbells and the Universal Gym, a weight apparatus with different exercise stations where free-weight routines are simulated, but usually work out on the Nautilus machines, devices Kelley described as "operating on a principle of iso-kinetic training that allows players to exert a maximum of contraction during a full range of motion, even at maximum exertion."

When he was a pre-med with a minor in physical education at Springfield, Kelley had no intention of becoming a trainer. While playing baseball in the Marines, however, he was made the team's unofficial trainer because he had more medical background than his teammates. He earned a master's degree in education at the University of Virginia and then Virginia Military Institute hired him to coach baseball. When the VMI football trainer died the first day of fall practice, the football coach asked Kelley to take over training responsibilities for the team. Kelley had the position for five years before coming to Dartmouth in 1967 as head trainer and freshman baseball coach.

Kelley also attends to the athletes on the track team and says the sort of injury he treats varies from sport to sport. Track injuries are mostly related to stress, pulled muscles for example, while football injuries separations, dislocations, and broken bones are usually the result of trauma. He also sees a large number of ankle sprains and knee injuries in football players, mostly among defensive and offensive backs.

"In treating an injury, it helps if you're out on the field to see it happen," Kelley said. After an injury a sprained ankle for instance has been recognized, diagnosed, and perhaps x-rayed, the first step is to control swelling through the use of ice packs and elevation. After the player is back on his feet, possibly using crutches, exercises are prescribed to rebuild damaged or atrophied muscles. Hot or cold packs are applied and the whirlpool bath might be used. Finally, the player who is ready for practice comes in for protective bandaging and taping.

No painkilling drugs are administered in order to get a player back out on the field, Kelley insisted. "At Dartmouth, when a player goes back after an injury he's recovered to the point where he doesn't need a painkiller. I've never seen an athlete perform well with a painkilling agent in his body. Pain is a warning signal that something is wrong. If you hide it, there's too much chance of doing irreparable damage."

What about other so-called performance drugs, I asked. What about amphetamines? "I have no knowledge of them being dispensed at the college level," Kelley said. Do any Dartmouth athletes use steroids to build muscle bulk? "Absolutely not. A great percentage of steroids is male testosterone. We don't know about the potential side effects. There is a danger of sterility. We have enough ways to add bulk safely. If a guy wants to get big, we can build him up without drugs."

Fully one-third of the freshmen who turn out for football have hang-over injuries from high school competition, mostly ankle and shoulder problems, such as chronic sprains and separations, according to Kelley. He blames the lack of rehabilitative care in the schools and favors a bill presently before Congress that would require a high school with more than 500 students to have a certified trainer on the staff. He said he is frightened by the number of high school players, and even Pop Warner league players, who are being taught the same head-first blocking and tackling techniques that cause so many injuries - bruised ribs, damaged kidneys, torn-up legs, hyperflexion of the neck, spinal damage - among much more muscularly mature professional and college athletes. A number of college competitors graduate with permanent aftereffects, in the form of calcium deposits and limited joint mobility, Kelley added. "It used to be that a football knee was a badge of courage," he said. "That's crazy. I try to keep the long-range view in mind."

The National Athletic Trainers' Association and the American Medical Association have issued a joint statement deploring the use of head-first tackles and blocks and calling for a return to making initial contact with the shoulder. Kelley concedes that compliance would probably result in more shoulder injuries but believes the reduction in more serious spinal injuries would be worth it.

He does not see a need to redesign almets, however, although he wishes officials and coaches would pay more attention to the aggressive ways they are used. What we do with helmets is a result of rules and coaching techniques. We need a real charge to officials to prevent spearing and other violations. I can count eight to ten late hits every game. The penalty should be more excessive for that type of play." He said the "primary function of a helmet should be to protect what it's enclosing. Today's helmet does a good job. We've gone from leather to suspension to air-padded helmets, like the Micro-fit, to helmets with alcohol-filled pads, like the Gladiator, to the present Bike Airpower and Pac-3 helmets. The Pac-3 is individually fitted and padded with two different kinds of rubber." Kelley handed me a Pac-3 helmet. "You see that inside layer of rubber? You could stand up and drop an egg on a piece of that and the egg wouldn't crack."

Aside from prohibiting blocking and tackling with the head, which Kelley doesn't think will happen here for some time - "The Ivy League is a microcosm of what's going on all over the country; we play the same football Ohio State does" - and more stringent calling of fouls, there isn't much, in Kelley's opinion, that can be done to significantly reduce injury in college football.

Conditioning helps, of course. Kelley worked with Blackman and Crouthamel before Yukica and believes that all three coaches have made use of the latest conditioning techniques, not only to improve strength and performance, but also to better the chances that their players would stay healthy. One thing that seems to contribute to injuries, Kelley has noticed, is playing on Astroturf. The traction is so good that tackles are harder, and when players hit the ground they don't slide. "I think we have more than the usual number of shoulder injuries playing on the Cornell and Penn fields," he observed.

I asked Kelley about bad sportsmanship contributing to injuries. Are teams out there trying to hurt each other? "We're in a good position in the Ivy League because we have to play everyone in the conference once," he said. "We play as hard as they do anywhere, but we have a sense of mutual admiration. In other conferences you don't often see the benches emptying after a game with players going to shake hands with the other team. You can't do something to a team here and know you won't be playing them for a couple of years. We use the gang tackle, yes. The coaches want as many people as possible on the ball. But that's the nature of football."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

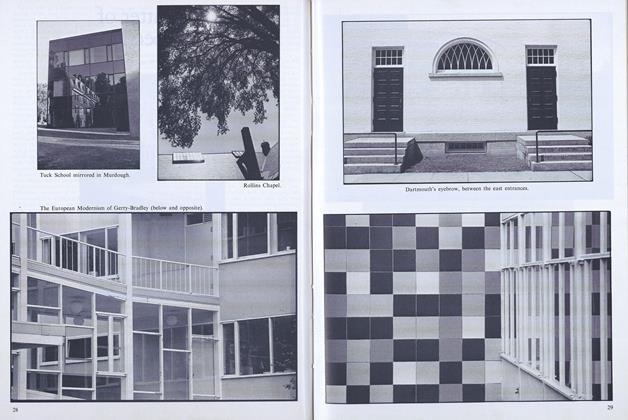

FeatureBeauty and the Beasts

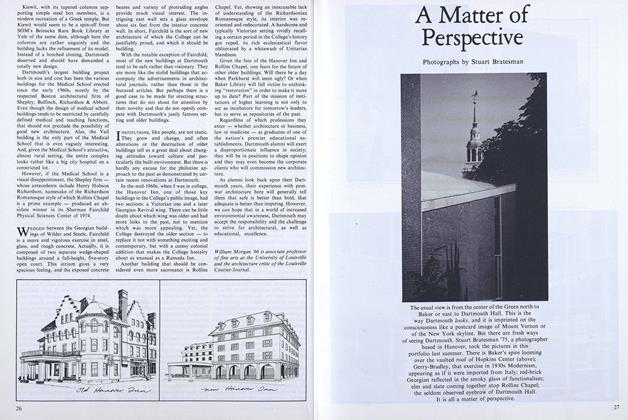

October 1978 By William Morgan -

Feature

FeatureConundrum of the Gridiron

October 1978 By Jack DeGange -

Feature

FeatureA Matter of Perspective

October 1978 -

Article

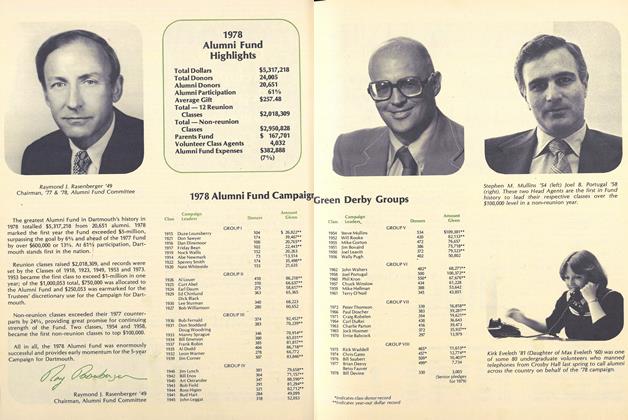

ArticleOffice of Development Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R.

D.M.N.

-

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticlePaddler, Climber, 4-term Planner

May 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleClean Sweeper

DEC. 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleStraight Shooter

December 1978 By D.M.N. -

Article

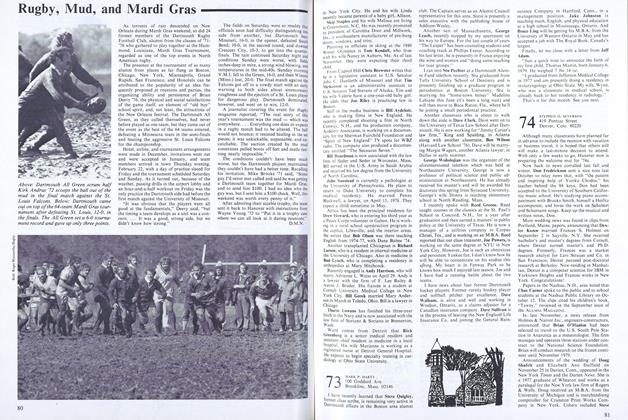

ArticleRugby, Mud, and Mardi Gras

May 1979 By D.M.N. -

Article

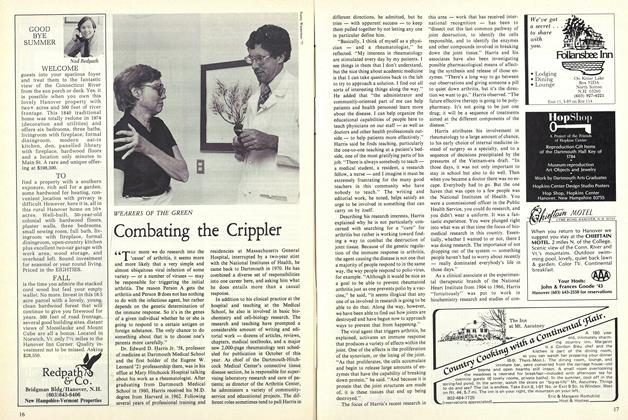

ArticleCombating the Crippler

September 1980 By D.M.N.

Article

-

Article

ArticleSong of 500 Gallons

October 1937 -

Article

ArticleNew Dorm Named

April 1940 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Award Conferred on Charles W. Bartlett '27

MARCH 1969 -

Article

ArticleSenior Alumnus

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Article

ArticleCameos of a Crisis

January 1940 By ALAN L. STROUT '18 -

Article

ArticleAmateur Movie Making

MARCH 1931 By Arthur L. Gale