THE American Revolution Bicentennial Commission refers to the celebrations commemorating the first 200 years of America's nationhood as the "Bicen," cynics and purists deride it as the "buycentennial" and Jere Daniell '55, Dartmouth's historian of the colonial and Revolutionary periods, calls it "just kicks."

Whether it is a show tracing the history of the barbershop quartet in America, a Bicentennial placemat, or an essay contest on the NFL's contribution to American history, Daniell "wouldn't have missed the Bicentennial for the world." (See also page 29.)

A serious scholar, with Experiment inRepublicanism, a monograph on New Hampshire politics and the Revolution, and New Hampshire: Years of Revolution to show for it, Daniell still has become an aficionado of the kitsch and color of this year's celebrations. "It's the extreme forms of commercialism that are the most fun," he says. "I'd just as soon see Old Glory cereal as Wheaties. They're both commercial." Daniell collects Bicentennial miscellany on his office door in Reed Hall, explaining, "The Bicentennial is great my door's been bare for years until this."

Very little fazes him: Bicentennial drycleaner bags, a heritage ball commemorating Abraham Clark's 250th birthday ("I don't even know who the hell Abraham Clark is"), or even a Rube Goldberg routine in which a baseball was taken by horseback from Boston to Philadelphia, zoomed around Veterans Stadium by a man with a jet pack, and handed to Robin Roberts who, naturally threw out the first ball. "I expected just what happened," Daniell remarks. "I expected things like Bicentennial ketchup and the fulfillment of those expectations is what's fun."

The source of all this may come from how we look at our Revolution. Daniel says that the American Revolution differs from other revolutions because it defines the point of national origin. His point is that "there is plenty of French history before the French Revolution and there is Russian history before the Russian Revolution. But the burden of parenthood in America falls on the Revolution." Americans apparently have always exploited the Revolution as a vehicle for selfexplanation. Even in the Civil War the South left the Union because it thought that the ideals of the Founding Fathers had been deserted. "When you go back to original principles in our society," he says, "you go back to the Revolution."

The different celebrations of the Revolution "tell you a great deal about the concerns of the society. People attribute to the revolutionists those qualities they yearn for in the present time." Although Daniell thinks those qualities are more difficult to identify today because there are "lots of people doing Bicentennial things" out of opportunism, much of the appeal of the celebration represents nostalgia for a "simpler, less complex society and a yearning for purity in politics. By contemporary standards politics in those days were a different kind of game. People in New Hampshire politics gained little if anything financially from their position in society and most didn't expect to."

Daniell, born and raised in Millinocket, Maine, has given about two dozen lectures with Bicentennial themes in New England towns during the past two years, and he doesn't think many of the myths surrounding Revolutionary figures can be debunked. "Myths have a life of their own," he says, "and even if I were going to try to strip away these myths, I couldn't do it. People would either be offended or believe what I said along with their myths. My role isn't to strip away myths but to avoid judgments and to help understanding. People are going to judge anyway, so their judgments might as well be based on understanding."

Almost in spite of itself, the Bicentennial probably has increased Americans' understanding of their history. "Many people know more about the Revolution because of the Bicentennial," he says. "There is a great exhibit in Quincy Market in Boston that thousands of people traipse past every day, learning a lot. That goes on on a thousand different levels. If it weren't for the celebrative parts there wouldn't be any interest in the other things."

Enrollment in Daniell's course on the American Revolution, however, is not unusually large this spring. "I don't think there is anyone in the course because he wants to celebrate the Bicentennial. Celebrations of bicentennials are associated with groups like the Colonial Dames and the Daughters of the American Revolution, and undergraduates are too young and probably too cynical to be interested in them."

Darnell has tried to protect himself from involvement in the ceremonial dimensions of the Bicentennial but has nevertheless become an authority on them. "I don't hate the Bicentennial," he says. "I can't help but get kicks out of the whole thing."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

Feature

FeatureReading and Writing History and Revolutionary Footnote

May 1976 By PAGE SMITH -

Feature

FeatureWhen Dartmouth Had Its Own State (Almost)

May 1976 By JAMES L. FARLEY -

Feature

FeatureThanks to Daniel Oliver, A Gathering of Lovers

May 1976 By DAN NELSON '75 -

Article

ArticleThe Green: A House Mover and an ex-President Proved Who Owns It (Didn't They?)

May 1976 By Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll, JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

May 1976 By WALTER C. DODGE, CHARLES J. ZIMMERMAN

D.M.S.

-

Article

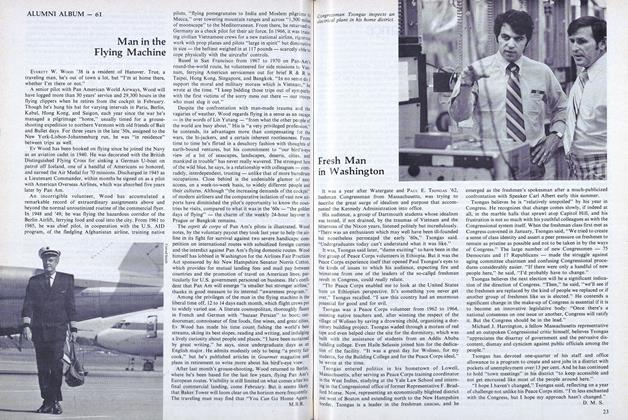

ArticleFresh Man in Washington

November 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

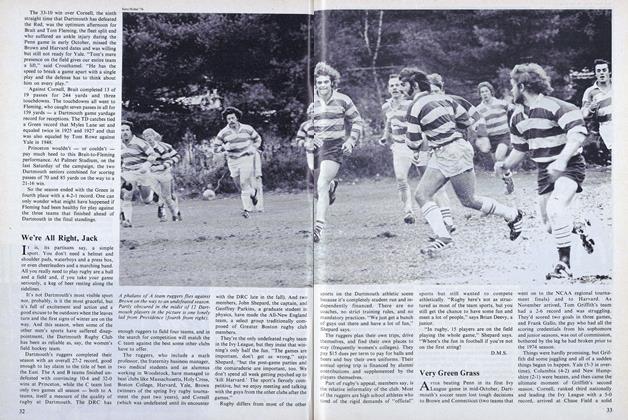

ArticleWe're All Right, Jack

December 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleBasement Admiral

December 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleMan of a Thousand Hats (more or less)

February 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

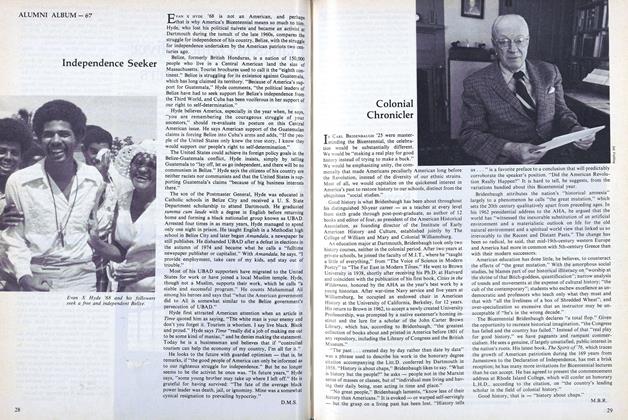

ArticleIndependence Seeker

May 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleThe Seniors Writ Large: Some Sit Right, Some Don't

June 1976 By D.M.S.

Article

-

Article

ArticleRetiring as Plant Superintendent

June 1953 -

Article

ArticleBequest Honors O'Connor.

DECEMBER 1965 -

Article

ArticleCOLLECTED VERSE PLAYS.

JANUARY 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleRESIGNATION OF PROFESSOR BARTLETT

March 1919 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS. -

Article

ArticleJohn James Audubon, Commercial Traveller

FEBRUARY 1930 By Frank C. Ayres -

Article

ArticleTHE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE

By William R. Gray