His grandfather was one of the New York Transit Authority's first employees and his father is a signal maintainer for the same rail system, but FRANK C. HERRINGER '64, the head of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) district, insists he wasn't destined to go into transportation.

Herringer, who left the top job at the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) in Washington last summer, got involved in transportation by accident. Now, at 33, he's managing one of the most sophisticated, controversial, and troubled urban mass transit systems in the world.

BART, with its 71 miles of track and 450 vehicles serving the San Francisco Bay area, was riddled with problems before it even opened. Service began in 1972, two years behind schedule, attended by a nightmare of mechanical and logistical problems. What had been considered a model for transit systems for the future rapidly began to look like a giant white elephant on wheels as trains were pulled out of service, passengers were uncomfortable, ridership dropped, and officials raised questions about the system's safety. Since July it's been Herringer's job not only to put BART back on track but to readjust the public's expectations. But "it's not a PR job," he says. "You've got to have performance."

Herringer views himself more of a management expert than a transportation specialist. In 1971 he was recruited - "out of the blue," he says - for the White House staff after seven years as a staff consultant and principal with the management firm of Cresap, McCormick and Paget, in New York City. His White House work brought him into contact with Claude S. Brinegar, then Secretary of Transportation. Brinegar offered him the job as UMTA administrator in December 1972 and Herringer accepted because "it was a young and growing organization."

Herringer stayed in Washington for two and a half years. In that time the money available for urban transit more than doubled, but ironically Herringer acquired a reputation as an opponent of rail systems. "We did a number of things to put the brakes on demand for new rail systems while I was UMTA administrator," he explains. "Every city in the United States with more than a million population was thinking of a BART-like system."

Herringer doesn't think operations like BART fit the needs of areas smaller than the San Francisco-Oakland district. Officials is such areas, he contends, "should be looking at something more flexible, something along the lines of trolleys and street cars." And Herringer adds that BART has helped transportation technologists realize that all transportation and congestion problems cannot be removed simply by installing a sophisticated rapid transit system. "You also need higher tolls on roads, restrictions on autos or higher parking charges, and auto-free zones," he says.

Despite the problems, which now include the possibility that BART will run out of money by October, Herringer feels construction of the system was a wise decision. "I definitely think BART should have been built," he says. "It was a good buy at the time." One of BART's greatest problems is that it didn't live up to the high expectations fostered by officials, consultants, and engineers. The planners were overambitious and overconfident in the technology, Herringer says, and the system was oversold. "It promised too much."

Herringer rides BART to work every day and spends most of his time re-organizing and staffing executive departments and dealing with what he calls "people problems." But he feels his job is "a lot of fun and a challenge of the first order." As BART administrator, he's in the "kind of position where your accomplishments and failures are very visible and where the feedback's immediate." In the wake of internal streamlining 14 senior executives have departed in the past few months, but as evidence of what the public regards as "performance," rail service also recently was extended into nighttime hours.

"There was a 51.5 billion budget and a lot of heady things at UMTA, but the impact of the work was far-removed and long range. You're not going to see your accomplishments for 15 years," Herringer says. "Here you make a decision and the papers are on your back in the morning."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

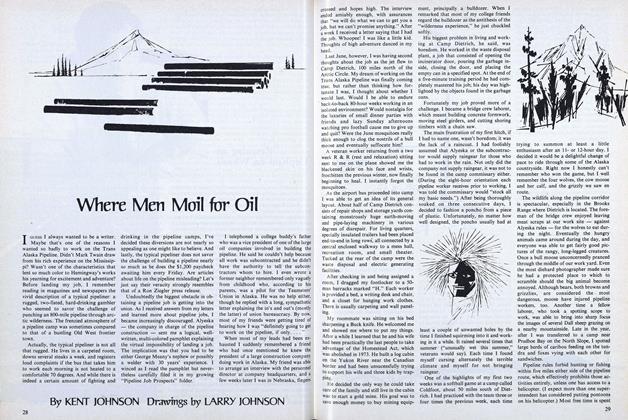

FeatureWhere Men Moil for Oil

March 1976 By KENT JOHNSON -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

March 1976 By McF. -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Article

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

March 1976 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON, JACK E. THOMAS JR.

D.M.S.

-

Article

ArticleDial M for Mogul

November 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleFresh Man in Washington

November 1975 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleMan of a Thousand Hats (more or less)

February 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleLife wifi Emma

March 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleIndependence Seeker

May 1976 By D.M.S. -

Article

ArticleThe Seniors Writ Large: Some Sit Right, Some Don't

June 1976 By D.M.S.