WHILE sitting with a few friends on the porch of the Hanover Inn several months ago, musing about the College and the alumni who were at that time descended upon Hanover for reunions, I was reminded that the class graduating that particular weekend would celebrate its 25th reunion in the year 2001. Reminded also of the filmic images which Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey had provided, I began to consider the possibilities for that reunion.

Kubrick's film features gentlemen attired in rather informal and nondescript clothing, which, if I am not mistaken, we today refer to as leisure suits. The film's antagonist is an almost-animate computer whose claim to fame is a clean error record. As the film progresses, the computer breaks the honor code by pulling behind-the-back moves on its human companions. Finally, after killing four fifths of the crew, the computer suffers the removal of its intelligence units. The image is, of course, readily transposed into thoughts of the 16th and penultimate President of Dartmouth College, surname Kiewit.

It was at this point that I decided my imagination was getting the better of me, and that I was using merely coincidental correspondences between elements of today's Dartmouth and the possibilities of the future to create an unnecessarily grim picture. And so, despite the dogged tendency of science fiction writers to predict the true nature of the future, and despite the fact that we already live in such a time that the corporate letter bomb may well be the greatest and most exclusive of status symbols, I decided to abandon this fantastic temporal foray.

But now, after returning home to a community which is changing, where lots for houses are getting smaller and yet, in a seeming paradox, people appear to be growing more distant, the future returns to trouble me.

Perhaps I'm just coming into an age in which change seems too prevalent. I know that when I was younger, nothing seemed to change, which bothered me almost as much then as change is beginning to bother me now. I imagine that it's a combination of that and the fact that things really do change more quickly now than in the past — if not of our volition, then at least as a direct consequence of advances in technology and commensurate increases in the speed of communication and information diffusion. Whatever the case, I am more aware of change now than in the past, and because it is invading my own little world, I am beginning to be wary of its advance.

Having returned home, I discover that where I have had an unobstructed view of fields and forest, with deer, fox and pheasant, there will soon be several dozen houses. With this growth I see my community begin to lose the very character which has attracted these newcomers.

While I sit here enjoying the animals, the death penalty has found new favor. While I don't feel secure either in condemning or supporting capital punishment, I am truly disturbed to see official indecision, in the form of changes themselves being changed, in matters of such consequence.

I am told of vast improvements in the academic standards at the College, and I am pleased by this. But I see such narrow vision behind this that I begin to fear the loss of perhaps the most important part of one's four years at Dartmouth — the human element, the part which carries on beyond the classroom, the part which today seems to be missing at so many other fine institutions of learning.

There are endless examples of personal, political and Dartmouth-oriented nature which serve to show the effect and present abundance of change. And while much of that change is both just and warranted, and while in most situations there is room for positive change, I would suggest that those responsible for instituting change, must, in this most changeable of times, begin to be more careful in plotting their moves.

For many changes once made are themselves immutable; there is no going back. And, perhaps worst of all, I perceive that a good deal of the changes foisted upon us are oriented towards a needless, indeed harmful, homogenization of values and beliefs.

Now I am sure that a touch of elitism colors these words, for I am in the comfortable position quite often to feel that things are fine as they are, and that change will lead only to nought. I realize that this position can be just as dangerous as one which constantly seeks change. And it is often the case, as illustrated by the influx of people into my community, that more people will gain by change than will lose. Here, for example,

it seems that some 40 families will benefit where only one loses. But I begin to think that while the various situations we encounter may not be perfect, while fewer people enjoy some of the finer things offered for our appreciation, there are many instances when this is far superior to an averaging of values for the supposed "common good."

Friedrich Nietzsche began his treatise Beyond Good and Evil by asking, "How could anything originate out of its opposite? For example ... the generous deed out of selfishness?" Later in the same paragraph, he replies by saying, "It might even be possible that what constitutes the value of those good and respected things (here, generosity) consists precisely in their being insidiously related, knotted and crocheted to these evil and apparently opposed things (here, selfishness) — perhaps even in being essentially identical with them."

My inference here is that in making changes which suppose to be in the interest of the majority, we often miss the nature and impact of that change. To summon back the most trivial and personal of my examples, who will really benefit from the building of 40 houses on the land I now enjoy? Those 40 families will have a place to live, and an address, but the very act of their occupying the land will destroy for them the opportunity to appreciate the infinitely superior state in which the land exists as I have known it. And along with their opportunity, they will take mine. Correlates exist for other changes of the nature I oppose. When we respect the thought that the act of change can all too often lead to the destruction of its goals without the substitution of better ends, and to the creation of various unforeseen and noisome side-effects, perhaps then we will be more careful in choosing our course.

Brad Brinegar, an anthropology majorfrom Lake Forest, Illinois, rows on theDartmouth crew and as a sophomore waseditor of The Jack O'Lantern. He willshare the duties of undergraduate editorand Whitney Campbell 1925 Intern withElizabeth Cronin '77 and Pierre Kirch '78.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSeeing Farther than the Green

September 1976 By BLISS K. THORNE and NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureHarvard Myths About Dartmouth

September 1976 By ERICH SEGAL -

Feature

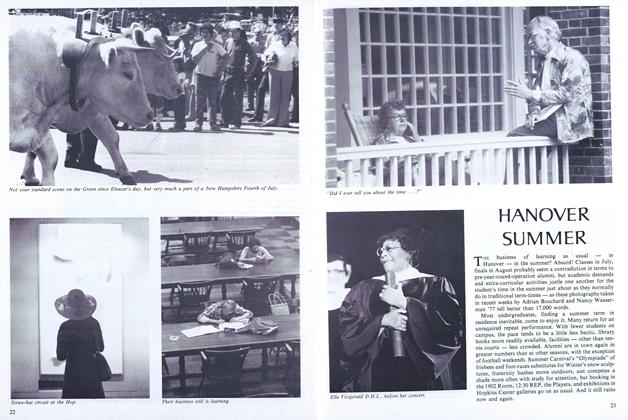

FeatureHANOVER SUMMER

September 1976 -

Books

BooksNotes on a common bond: the federal city, that summer in Philadelphia, Essex County in revolt, and disaster in Ohio

September 1976 By R.H.R. -

Article

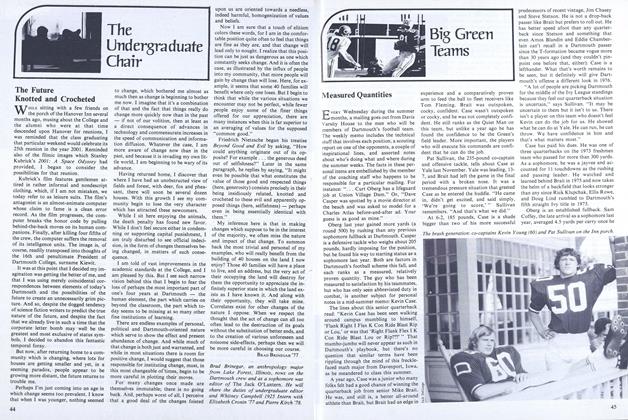

ArticleMeasured Quantities

September 1976