Considerable excitement attended the arrival of Margaret Mead in Hanover as the second annual Class of 1930 Fellow, especially after it was announced that tickets would be required for her main address: “Cultural Pluralism and Political Decision-making.” So on a chilly November night we crowded into Spaulding Auditorium to get a glimpse of the venerable 77-year-old anthropologist. We overheard one student say, “I’m only here because of the tickets. I figured I’d better get one because not everyone can go.” Some also professed interest in ob- taining “a little cultural enlightenment.” In any case, the tickets proved a fine advertisement, as a capacity crowd jammed Spaulding and others watched up- stairs on closed-circuit television.

A student observed archly that an expert on primitive cultures ought to feel right at home in Hanover. Whatever the reason, the anthropologist seemed relaxed and in- formal as she leaned over the speaker’s table and challenged the audience with her direct and steady gaze. Her impromptu remarks followed a winding trail of reminiscences, current aggravations, and predictions for the future, but the main focus was the idea of cultural pluralism and differing perceptions of its value over the past few generations.

From the Anglo-Saxon viewpoint, “everyone has customs but us,” Mead noted wryly, “and we find them so quaint that we wish that we had some of our own.” Many nations have struggled with the problem of peacefully maintaining a number of different cultural groups, but the approach to this problem has changed greatly over the past 20 years. In the fifties the strongest nations tried to “spread a uniformity over the entire world.” She said that the emphasis then was on technology, and giving its benefits to everyone. Confor- mity was celebrated, and the American ideal was a man in a gray flannel suit.

Now, according to Mead, “we are mov- ing toward an attempt to value difference.” Cultural groups define themselves in terms of their exclusion rather than their inclusion in the mainstream. People are linked together by their variance from “white, middle-class, Protestant men.” Quotas, once a means of keeping people out, now represent the number of outsiders wanted in.

Just as there were tragic problems with the attempt in the fifties to eliminate diver- sity, Mead also recognized some disadvan- tages to the assertion of pluralism. There must, she said, be a reasonable amount of uniformity in order to preserve meaningful diversity.

Mead came to Hanover for two full days of seminars, classes, and panel discussions besides her main speech. President Kemeny, in his introductory remarks, praised the 1930 Fellowship for its relaxed approach. “It used to be a hit-and-run af- fair having distinguished speakers come to Hanover,” he noted. “We picked them up at the airport, took them to their audience, and then loaded them back on the plane again. The Class of 1930 Fellowship provides an opportunity for the speaker to get to know Dartmouth, and vice versa.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Article

ArticleResident Rotiferologist

December | January 1977 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

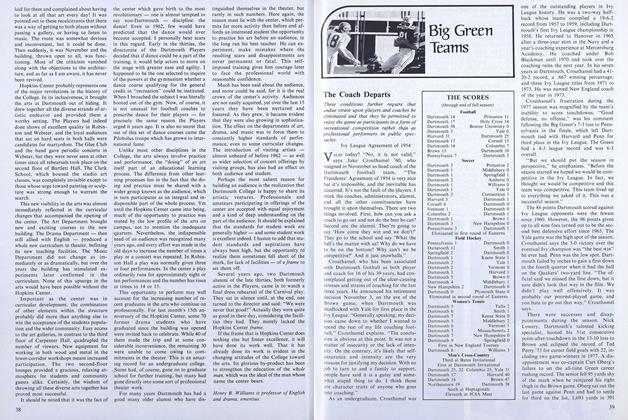

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65