The last time we checked up on the Concord String Quartet, at the end of its first year of residence at the College, its members were adjusting to their roles of being both performing musicians and adjunct assistant professors who teach music. To conclude their first three-year sojourn here (this spring, the Concords have renewed their residency for another three years), they are performing the entire cycle of 16 string quartets composed by Ludwig van Beethoven.

A press release that we received not long ago stated that "the Beethoven cycle holds a place in the chamber music repertoire unrivaled by any other group of compositions, and the performance of this monumental body of work is considered one of the greatest achievements for a string quartet." We wanted to talk to one of the Concords about the Beethoven cycle, so we called at the Hopkins Center Office of Information to see what could be arranged. A very accommodating woman named Marion Bratesman, who is the director of that office, said that she knew the Concords would be in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, that night and Spring-field, Massachusetts, the next night, but that she did not know the quartet's schedule afterwards. She was very excited about the Beethoven cycle because it had been a sellout in the Spaulding Auditorium, which contains 900 seats, and because the Hanover 'Planning Board, the pinnacle of local government, had post-poned one of its meetings so that it would not conflict with one of the Beethoven cycle concerts.

We were able to chat with Norman Fischer during the next week while the Concords were taking several days off from rehearsal. Norm Fischer plays the cello in the Concord String Quartet and is an adjunct assistant professor of music at the College. Come to Dartmouth able to play the cello and Norm Fischer will teach you how to play better and it won't cost you extra beyond your tuition. Come to Dartmouth able to play the violin or viola and Mark Sokol, Andrew Jennings, or John Kochanowski, who are also members of the Concord String Quartet and adjunct assistant professsors of music, will teach you how to play better for no extra cost.

We asked Fischer what it was about Beethoven's quartets that made them, to quote the Hopkins Center press release, "monumental." Professorily, he began at the beginning, and delivered an impromptu lecture on the history of the string quartet. Haydn, he said, invented the form in about 1750. Later, Mozart heard one of Haydn's compositions, Opus 33, realized the greatness of the four-voice form, and began to compose string quartets. This brought Fischer to Beethoven, the topic of our discussion. Beethoven did not begin to write quartets until after he had studied the Haydn and Mozart quartets. "Beethoven," Fischer continued, "took the formal mold of the quartet and went beyond Haydn and Mozart. Then something snapped in Beethoven that changed the history of music. He realized he was going deaf and it shook his fundamental beliefs. Here he was, a musician going deaf!... He was crying out, 'damn it, this is unfair! 1 love music, and here it is being taken from me!' ... and then you see the quartets that follow."

Fischer began to talk about Opus 59 and Opus 74 and Opus 95, We knew what the word "opus" meant, but we were never sure what the announcer on "Sunday Concert Hall" meant when he read a list of opuses, so we took this opportunity to ask Fischer for some background about opuses. He said that an opus is a particular publication of compositions, and that the publisher assigns an opus number to a publication of compositions when it comes out. About the use of opus numbers, Fischer said: "It's just like picking up a catalogue and saying I want number A 39526." He went on to say that the opus numbers of Haydn, Mozart, and Shubert are not chronological because the publishers of Haydn, Mozart, and Shubert did not release those composers' works in the order that they were written, but that Beethoven's compositions for the most part are numbered chronologically. Back to Opus 59, and Opus 74, and Opus 95: "They have a different quality. They're much more symphonic, in the sense that the piece does not rely as heavily on the first violin. You see the other members participate more actively.... In the classic model, the first violin carries the melody line. In these quartets, you have other voices, the first violin is not so prominent, the others are doing things so interesting that it draws you from the main melody. It starts freeing up four equal voices ... the sound is wide open, the melodies seem to go on forever."

Fischer was now ready to answer our question: What is it about Beethoven's quartets that make them monumental? Fischer: "The simplest answer is that it is the greatest body of music. The demands the music places on you are so great that to say 'This is how we feel about it' is making a statement.... It makes great demands on a player. It demands tremen-dous emotional drain, a tremendous understanding of music, it simply taxes every element of you that makes you a musician. The transcendental beauty of these quartets, the profundity of the music - its intensity and passion - can't be duplicated in other mediums, and hasn't been duplicated since." He talked as though Beethoven's blood flowed through his veins. "Why would somebody say that the late Beethoven quartets have been the greatest achievements of Western Civilization?" Has somebody said that? "Yes. They go beyond the greatest science discovery, the greatest mathematical achievement, any work of art. They say more about the human condition, about feelings. They speak to someone in a way no other piece can." He mentioned the Beethoven C sharp quartet. "What is said in that piece is timeless. It will always be great."

When the Concord String Quartet began its Dartmouth residency three years ago, Peter Smith, who is the director of the Hopkins Center, told the quartet that he had a dream of having the Beethoven cycle played at Dartmouth by a resident string quartet, and asked whether the Concords would be willing to attempt it. Fischer, Sokol, Jennings, and Kochanowski discussed and thought about the idea for several weeks, and then told Smith they would play the Beethoven cycle at the end of their three-year contract. From that point on, the goal of the Beethoven cycle shadowed every repertoire decision made by the quartet. The last of the Beethoven quartets will be performed by the Con-cords on May 17 in the Hopkins Center, when they play Opus 18, number 3, Opus 59, number 3, and Opus 130. "To play all of Beethoven as a body in a series," said Fischer, "to play them all, is the ultimate expression of a quartet. Beethoven put himself out to the nth degree. He realized the significance of the medium. Composers of the present day wait until they are mature before they write a string quartet. It's all because of Beethoven - what he achieved."

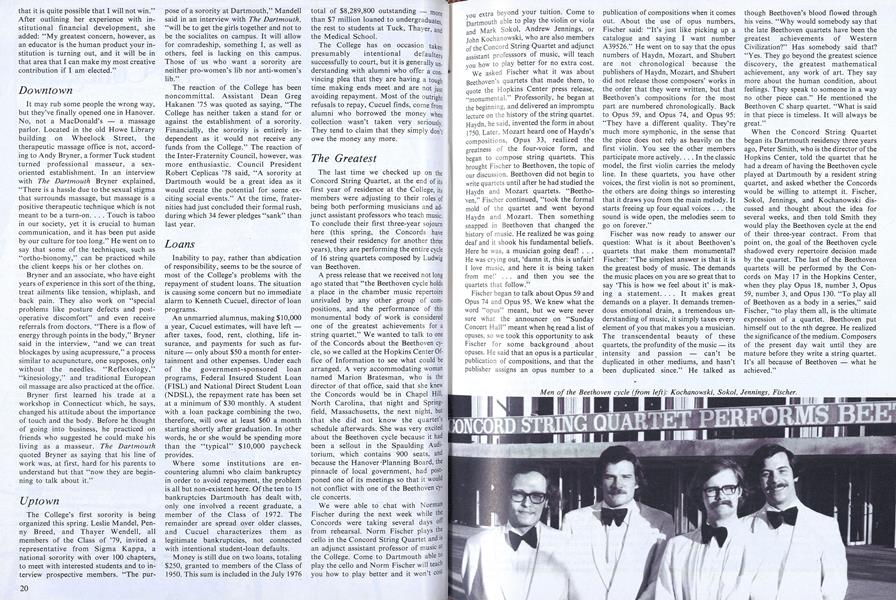

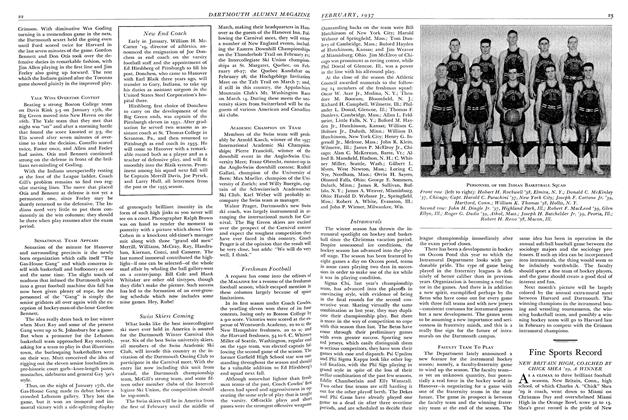

Men of the Beethoven cycle (from left): Kochanowski, Sokol, Jennings, Fischer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19

Article

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth 33, University of Vermont 0

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleSENIOR ELECTIONS

April 1920 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Appointments

July 1948 -

Article

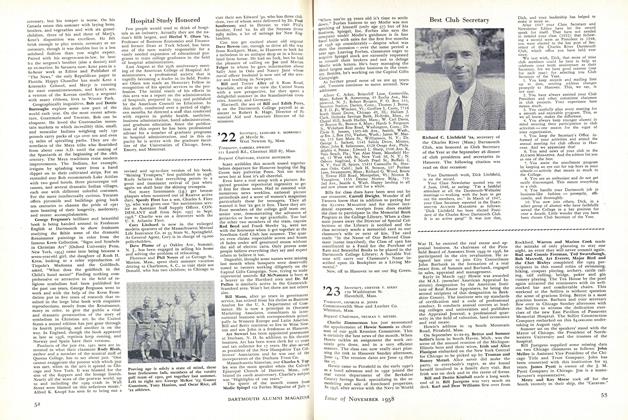

ArticleBest Club Secretary

-

Article

ArticleDeath of Blickensderfer

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleNEW BRITAIN HIGH, COACHED

February 1937 By Crarles W. Smedley '14