NEW ENGLANDERS have only themselves to blame if their farmlands and steepled villages are systematically overrun by down-country hordes. The invasion could be stopped by a single piece of legislation, by which the media, from land developers' brochures to alumni magazines, would be required to show their seductive pictures of fall colors and snowy hillsides only when accompanied by the horrors of mud season. Portraits of sedans axle deep in rutted roads, or of a family's slime-covered boots just inside the mudroom door, might undo forever the myth of picturesque New England life.

In the meantime, mud season is a fact of life for New Englanders, with enough of an identity to draw a good crowd last month to a Dartmouth Saturday Seminar with Lou Renza (English) and Peter Whybrow (psychiatry). Born in England, where he took his medical degrees, Whybrow has written on psychosomatic illness. He now heads the Department of Psychiatry at the Medical School and is a recognized expert on depressive illness — although he claims to have yearned once for the life of a veterinary surgeon." Renza specializes in 18th- and 19th-century British and American poetry. His current interest in Edgar Allan Poe barely explains a fanatical preoccupation with the New York Yankees and (at this time of year) the annual rite of spring training.

Renza opened the seminar: "Human beings tend to impose emotional and human attributes or meaning to spring. We impose cliches on spring, or the cliches of human discourse impose themselves on our sense of spring — so it is almost as hard to write about spring, for a poet, as it is to write about your mother." Renza sees no adequate reason why we should perform this imposition on neutral nature, although he admits that the offense is widespread: "When I was in Southern California, I seemed to have been living in terms of an ideology of the sun. Everybody somehow feels compelled or not compelled to go outside and have 'a good time.' That sunshine, that endless sunshine — it almost made one feel perversely suicidal. Even radio broadcasters in Hanover tend to say, 'lt's raining outside; it's not a good day.' Why should it be a bad day because it's raining? How did rain get such a bad reputation?"

English teachers like to find in good poetry the antidote for our misapprehensions. For a seminar on a New England theme, then, the poetry would naturally be that of Robert Frost, and Frost, says Renza, "sees poetry as nature or, to put it another way, he tries to see (through poetry) nature as Emerson saw it: the Not Me. That is, he tries to reduce or take away that human imposition, that human selfishness, by which we use nature to describe our own consciousness, and, also in a kind of utilitarian manner, don't put it back. In this way, we in effect mentally pollute our physical environment."

Pollution! We somehow want to clean it up. But not so fast. The cliche contains a grain of truth worth preserving. Take, for example, our tendency to think of spring and mud season in terms of repetition or even of resurrection. The grain of truth, as Whybrow the psychiatrist reminds us, is that the incidence of birth and death really does increase during the spring. Our mistake lies in reading the data as morally loaded, arbitrarily considering first the deaths and then the births, and calling the process resurrection. There we catch Ourselves reading moral messages into natural phenomena, and the more we do it, the more we get out of touch with our world, with life itself. In common parlance, that is called mental illness.

FEARING for our psychic lives, then, we might warily agree to drop the cliches and take spring and mud season "straight." A poet like Robert Frost can help us to see things straight, but we should not expect him to make nature artifically simple for us. In one way, we can read Frost's poetry as simple, pastoral New England romanticism. But if we are taking him straight, we will confront a poetry which is every bit as bewildering in its ambiguity as the nature it describes. Frost lived up to his name as well as any poet, for there is a quiet, sometimes partially destructive, often subterranean power beneath the natural surface beauty of his verse. He is complex, disturbing, a poet whose vision of ambiguous nature and human nature can be as chilling as a Nor'easter.

Few Frost poems show this ambiguity as well as the familiar "Mending Wall." The poem can be read — probably should be read at least once — comfortably, as a simple verse about a spring ritual: repairing a frost-damaged stone wall. That is only the beginning, as we are warned by the poem's first word. "Something," in a spring poem where we need a little reassurance, is too ambiguous, almost desperately uncertain. ("We are brought up, culturally," says Renza, "not to want indeterminancy.") We want from the poem a bucolic rhyme. A simple farmer and a pastoral poet mend a wall. We are out of luck, then: the wall is not mended, can never be mended, once and for all. Not "mended wall," but "mending wall":

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.And some are loaves and some so nearly ballsWe have to use a spell to make them balance:

"Stay where you are until our backs areturned!"

And what about the menders themselves — the poet and the farmer? It is a temptation to judge them, separately, as the unthinking farmer and the perceptive poet:

There where it is we do not need the wall:He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get acrossAnd eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.He only says, "Good fences make goodneighbors."

White pine, probably, we want to say. Good for furniture. Not much else. Too pitchy for cordwood. But an apple orchard. Food. How quickly we make that little judgment. For such a poor reason we would blame the poem's message on the farmer. But the poet initiated this ritual mending:

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;And on a day we meet to walk the lineAnd set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

Suddenly, then, the poem is about two equal men, mending "the wall between us."

Why do they do it? There are two reasons, really. First, the wall is down: " ' ... Something there is that doesn't love a wall/That wants it down.' " "Something" might be nature, "that sends the frozen-ground-swell under" the wall. The frozen-ground-swell might be frost — or Frost. The poet wants the wall down, finds it unnatural, perhaps. There are no such walls in nature. Still, the poet initiates the mending. He knows the value of a wall in human nature. Men fight over "secure borders." Everything between Frost's farmer and poet depends upon a secure border. In a way, the two are just parts of the same Frost psyche: The poet in him wants the walls down, but the man in him knows they must be mended:

Before I built a wall I'd ask to knowWhat I was walling in or walling out,And to whom I was like to give offense.

In the realms of human nature, it can be beneficent to "give a fence." It might be an offense not to, since mending the wall brings poet and farmer naturally (however ironically) together. Building poem and wall holds everything together.

The farmer's "Good fences make good neighbors" is not a new thought. It is, as Renza points out, a refrain, handed down through human nature from father to son, since men dwelled in caves:

I see him thereBringing a stone grasped firmly by the topIn each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father's saying,And he likes having thought of it so wellHe says again, "Good fences make goodneighbors."

Frost's understanding ranges this far with ease, but he is primarily a New England poet. In many ways, he is a Dartmouth poet. He was a palpable presence on the campus even after he died. We kept expecting him to show up at Commencement. Many of us could have used his inspiration each spring, too, as we — and the mud — returned to the campus. He might have helped us understand why we heard that in spring New England was replete with suicides — more so than any other part of the country. And why a mathematics professor shot himself in the woods one spring.

Whybrow hints that a contributing cause to mud season illness and suicide is our compulsive struggle to behave in spring exactly as we would in summer or fall — to ignore, or even combat, the elements. Frost's poetry urges us to rein in the domineering spirit, to remember that nature is more powerful than human nature. In "Reluctance," he wonders why, in the heart of man, Was it ever less than a treasonTo go with the drift of things,To yield with a grace to reason,And bow and accept the endOf a love or a season?

Going with the drift of things might mean yielding a little to the inexorable passage of the seasons: fall-to-winter, winter-to- spring. Patience is all, as in "The Onset": "I shall see the snow all go down hill/In water of a slender April rill." Going with the drift can be harder than it sounds. We do not readily'admit to a greater power — of nature or of God — and can easily find ourselves remaking the world to fit our needs, planting peach trees in New England (see "There Are Roughly Zones") until, out of patience and energy, we finally agree with Frost (in "Good-By and Keep Cold") that "something has to be left to God."

"We should thank God," says Peter Whybrow, "for the winter season, for the mud season, because they are times of challenge. Interplay with our environment has made us what we are (the living things on this planet), and that is what will continue to make us what we are. Challenge is the shaping force, and adaptive fitness the measure of mastery in the service of life. This is a simple, Darwinian principle."

Whybrow is a marvelous example of the value of a sense of humor in facing the rigors of a New England winter or spring. He offers a tongue-in-cheek prescription for surviving mud season, but not until (like Frost) he has cut man down to size, made him more realistic about his power over nature. "Life is a splendid, glorious afterthought in creation," Whybrow reminds us. Most of the universe is inanimate, amoral; it just exists. There is nothing good or bad, perfect or imperfect, about it. "We are probably the only creatures that can conceive of perfection. That's a terrible, disastrous thing to think about, by the way, because it just doesn't exist."

Wanting to create our own sense of perfection is what probably gets us into trouble during winter and spring. In winter, we cannot stand snow-covered walks and driveways, and waste considerable energy clearing them. In spring, we cannot stand the thought of immobility, so we compulsively drive our cars on impassable New England dirt roads — and get stuck. Some kind of puritanical imperative drives us toward this indomitable — and thoroughly maladaptive — image of ourselves. The striving after perfection can make the rigors of the seasons harder, not easier, to manage. Furthermore, it compels us to miss the beauty of those natural ambiguities which Frost would most gleefully celebrate.

But, says Whybrow, with a grin, we do have a choice. If we do not wish to face the rigors of the climate head on (and take our chances of physical or mental ill health) we should indulge in a little forward planning. Here is his "prescription" (for surviving mud season and hence enjoying spring), which is founded upon two overall principles:

1. Keep in mind that change is the only certainty, and that it is good for you; stress is good for you.

2. While you seek for mastery, do not expect perfection.

These principles in place, he offers two remedies. The first he prescribes for the chronic problems of living in the colder, changeable climates; the second for the acute problems of mud season itself:

DR. WHYBROW'S ELIXIR

1) Choose your parents very carefully. If you are going to live in a cold climate, choose fairly short people, fairly squat people, the hairier the better.

2) If you want to live in a coolish climate, it is better to be female, so try that if you can.

3) Avoid being reared in a dark cupboard. This can be disastrous to your climatic adaptation. (Try putting a plant in a cupboard, for example. It will grow tall and white, a very bad combination.)

4) Please avoid growing fleshy appendages, such as earlobes. If you must grow appendages, cover them up.

5) Practice growing hair quickly.

DR. WHYBROW'S BALM.

1) Do not wrap up too soon. Continue to wear your bathing suit well into November.

2) Eat a lot. Don't worry about these diets and things for getting slim. What we need is a good book as to how to eat fat and acquire it.

3) Try to develop, in the psychological sense, a very civilized pessimism. As the day lengthens during January, don't get too excited. Remember what the farmer says:

A summerish January,A winterish spring.

A warm February, a bad hay crop;A cold February, a good hay crop.

4) Remember always, that the Ice Age made us great. As they say in England, "Cast not a clout 'til May be out." Don't take any of your clothes off once you get them on.

5) Work on some rituals, if you can. They're very important.

6) Buy a wood stove for a pet.

7) Get a cat. Sometimes mastery will not come easily, and when it doesn't, you really need something like a cat. I can throw ours at least 14 feet into the nearest snow drift, without even opening the door. He loves it.

"Having developed," says Whybrow, "enormous strength by early March, when you have tuned yourself into the most wonderful animal that you are ever likely to be, I think that there are several alternatives":

A SPRING TONIC

1) You can write poetry. (Renza referred to mud season as spring training for poets.)

2) Or fall into a passionate love affair.

3) Or you can buy yourself a set of Belgian horses, and just hire yourself out to people who are getting stuck in the mud.

4) Or, if all that fails, you can get depressed. That is one you certainly shouldn't overlook. I'd say that hasn't been used as much as it should have been. (As a psychiatrist, Whybrow is prejudiced.) Only about three per cent of the population uses that route.

5) Finally, a possibility which would clearly require a federal grant, you can turn into a hippopotamus. This notion came to me because of a rather wonderful song, written by Flanders & Swann:

Mud, mud, glorious mud,There's nothing quite like it for cooling theblood;So follow, then, follow,Down to the hollow,And there let us wallow in glorious mud.

Spring training for poets

Steven L. Calvert '68 gave up "theunpromising future of full-time collegeteaching" to become the director of theDartmouth Alumni College & Seminarprograms in 1976.

The Frost poetry is reprinted from Selected Poems of Robert Frost. Holt,Rinehart and Winston. Copyright © 1962.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAn Unease on Webster Avenue

April 1978 By Mark Hansen -

Feature

FeatureOur Captivating Compendium

April 1978 -

Feature

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

April 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Article

ArticleAlchemist to the College

April 1978 By S.G. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1978 By DOUGLAS WISE -

Article

ArticleHeadmaster

April 1978 By M.B.R

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCONTRIBUTORS

MARCH 1995 -

Feature

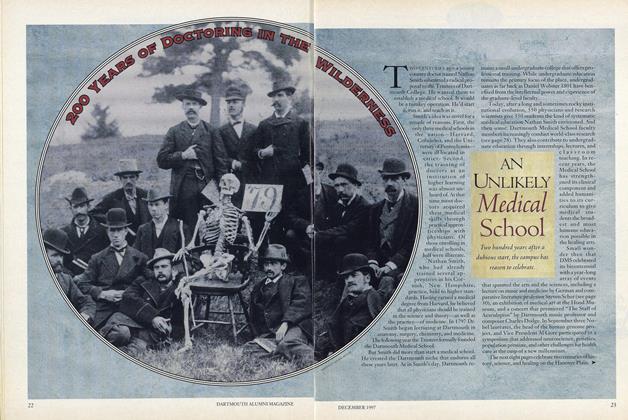

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

DECEMBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFOUR RULES FOR INVESTING A WINDFALL

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT GLOVSKEY '73 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Civil Action

July/August 2001 By ROBERT SULLIVAN ’75 -

Feature

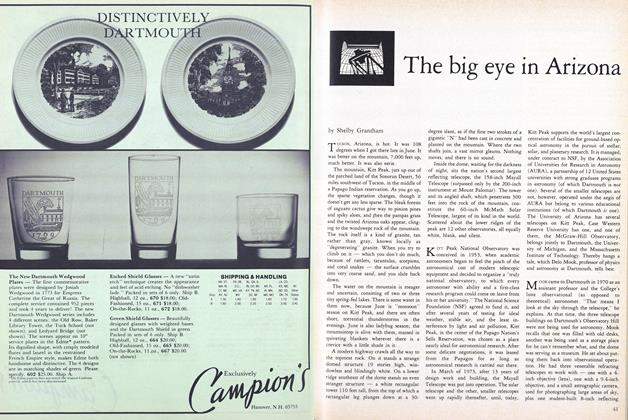

FeatureThe big eye in Arizona

SEPTEMBER 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

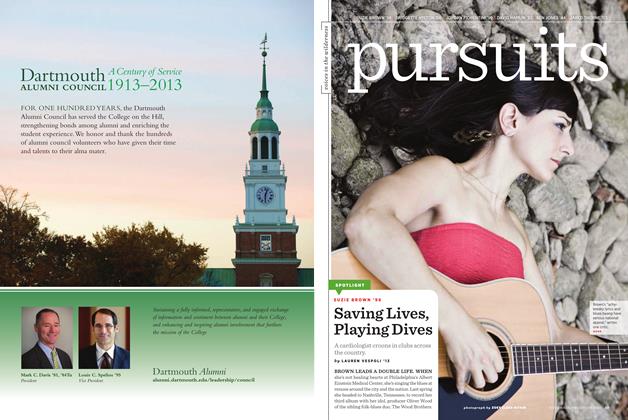

FeaturePursuits

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By ZOEY SLESS-KITAIN