Athens and Jerusalem and the curriculum

What should colleges teach. How? Why? The questions are hardly new they were beingdebated in Athens 2,000 years ago and at Dartmouth 200 years ago but a reaction tocertain notions unfurled over the barricades of the late 1960s poses them again. At Harvard,at Brown, and at dozens of other institutions there lately has been worry aboutacademic anarchy, curricular freedom versus curricular discipline, eternal verities versusthe relevancy of Now and Me. What is an educated person? What, indeed, of the cumlaude illiterate?

The issue comes up at Dartmouth in connection with a faculty study of the advantagesand disadvantages of the academic calendar whether courses can properly be taughtand learned and absorbed in a rigid ten-week term. In 1958, Dartmouth abandoned itssemester calendar for a three-term system, later adding the wrinkles of a summer termand year-round operation. Now, the faculty appears roughly divided into the humanistswho favor'longer, more reflective periods of study, the scientists who like the comparativelyshort bursts of the present calendar, and the social scientists who residesomewhere in the middle.

The debate begins in earnest this month with the completion of a report by the Committeeon Curriculum and Year-Round Education, which, as the name implies, has concerneditself with the What and the Why as well as the How. As one member put it," 'Whither mankind' not 'whither the ten-week term' should be our watchword." Reportson the faculty's deliberations will appear in future issues. In the meantime, the article thatfollows represents a point of view only recently scorned as "traditionalist" or, worse yet,"conservative."

DURING its most recent phase, Dartmouth College has done useful things, most of them of an operational nature. It has not, however, thought effectively about the substance of a liberal arts education.

We have instituted coeducation and the Dartmouth Plan. Both of these are on the whole large plusses. But the College has not within living memory given serious consideration to the shape and purpose of the curriculum as a whole. Both students and faculty are aware that something is missing at the core of the entire operation.

The next decade at Dartmouth should see a serious effort at curriculum reform. For good reasons, no doubt, the 19th-century utilitarian and social darwinist Herbert Spencer is not now in good repute, but he put the issue as well as anyone ever has. He spoke of the "enormous importance of determining in some rational way what things are really most worth learning." Spencer's answers would not be mine, but he asked the right question.

The majority of students I meet at Dartmouth know where they are in space, but not where they are in time. They live in Hanover, New Hampshire, but they do not know where they came from. They are not aware that they also inhabit Western civilization. They do not know that this civilization had a beginning and went through a series of momentous developments. An old professor of mine, at Dartmouth, memorably defined the "citizen" as the person who, if necessary, could re-found his civilization. In no sense at Dartmouth are we even attempting to nurture citizens in that sense.

The present curriculum has many virtues. It contains brilliant individual courses. But most Dartmouth seniors do not know much more about the civilization of which they are a part than they did as freshmen. "He who is ignorant of what happened before his birth," wrote Cicero, "is always a child."

THE history of academic institutions has a periodic character. A historical cycle in a college or a university begins with an idea, an institutional inspiration, a consensus. Then that consensus becomes routinized. In the course of time, the institution experiences a loss of energy, a sense of fatigue. Those involved begin to forget just what it was they were supposed to be doing. These cycles in higher education seem to last about 40 to 50 years, and when a cycle comes to an end the college or university must recover that sense of inspiration and re-invent itself.

American colleges and universities in the beginning were mostly designed to produce Protestant clergymen, and the curriculum was naturally designed to that end. In their next phase, they were supposed to produce statesmen capable of administering a republic, and citizens capable of understanding the requirements of that enterprise. Next, colleges and universities understood that they were to produce businessmen-citizens, and, with the elective system as introduced by President Eliot of Harvard, the curriculum began to shiver with a sense of intellectual uncertainty. Was "customers' choice" a satisfactory principle of course selection?

The present phase at Dartmouth, now coming to an end, began after the Second World War. It was symbolized, in its initial and "inspirational" period, by President Dickey's Great Issues course. The title of that course was portentous. The "great issues" were not back there in the classroom; they were not the issues dealt with by Plato, Machiavelli, or Shakespeare. The "great issues" essentially were current events. Innumerable subsequent decisions flowed from that initial direction. What we were really supposed to be concerned about were problems of public policy. It was not difficult to discern behind all this the implicit goal of the Dartmouth curriculum plus all the programs, speeches, guests, honorary degree recipients, and so forth which were added to it. Dartmouth was supposed to produce, ideally, the federal official; which, indeed, President Dickey had been before coming to Dartmouth. Of course, not every graduate could become a bureaucrat. But, at the very least, every graduate would be attuned to the ethos of the bureaucrat. Even if he were a lowly businessman, he was at least supposed to be a Merritt Parkway internationalist deferential to the federal bureaucrat.

With virtue located in the area of public policy, international peace, race relations, and the like, attention seemed to wander from what the College was actually doing in the classroom. Of course, the Great Issues approach ultimately failed. Dartmouth seniors grasped, however obscurely, that existence held more than could be found on the first ten pages of the New York Times. But no subsequent rationale emerged which would provide some sort of guide for making decisions on what courses should or should not be offered.

During its most recent phase, accordingly, the Dartmouth curriculum has grown not in response to any conception of what an educated person ought to be, but in response to various demands. If a member of the faculty proposes a course, and if a decent case can be made for that course on its own terms, then it has a very good chance of being included in the catalogue. If a segment of the community desires some course, and creates a constituency for it, then that course has a very good chance of being included in the catalogue. A few vague requirements for the bachelor's degree remain: freshman composition and a freshman seminar, several courses distributed among the science, social science, and humanities divisions, and a "major." But the majority of students remain puzzled, and rightly so, about the significance of it all.

IT is actually possible for a Dartmouth student to receive a bachelor of arts degree, a degree in the liberal arts, without having read Homer, Dante, or Shakespeare. That fact is absolutely astonishing to me. Not only can an excellent case be made for those three writers as the best, perhaps by far, in the history of the West, simply on merit; they also express, and express profoundly, successive epochs of human consciousness. They are both intensely local and universal.

"Poetry, story and speculation," wrote the late Mark Van Doren, one of my most important teachers and also a friend, "are more than pleasant to encounter; they are indispensable if we would know ourselves as men. To live with Herodotus, Euripides, Aristotle, Lucretius, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Pascal, Swift, Balzac, Dickens, or Tolstoi — to take only a few names at random, and to add no musicians, painters, or sculptors — is to be wiser than experience can make us in those deep matters that have most closely to do with family, friends, rulers and whatever gods there be. To live with them is indeed experience of the essential kind, since it takes us beyond the local and the accidental, at the same moment that it lets us know how uniquely valuable a place time can be." Van Doren was himself a master of English prose. It is worth reflecting on the last eight words of his paradoxical phrasing.

Without the great stories and songs and speculations of the West, what Matthew Arnold called the best that has been thought and said, we are emotionally and civilizationally impoverished. We do not know where we are or whence we came. In the eloquent title of a story by Lionel Trilling, we are of this time, of that place, and what does it matter.

FOR half a dozen years at Columbia College, I taught a course designed by Mark Van Doren and a few kindred spirits during the late 19205. As a student, I had transferred in 1949 to Columbia from Dartmouth after two years because, to be frank, nothing much seemed to be going on intellectually in the English Department at Dartmouth. Most of the members of the Dartmouth English Department then published little more than their names in the Hanover telephone directory. Columbia, from a literary point of view in 1949, was the New York Yankees. They had Van Doren, Lionel Trilling, F. W. Dupee, powerful men, all of them in print all of the time. They encouraged me to finish my undergraduate work at Columbia, and I joyously agreed to do just that.

Graduate work at Columbia, Naval service in the Korean war, then back to Columbia. I had scarcely bought a decent set of civilian jackets and slacks before I was asked to jump in and teach the great undergraduate course at Columbia, called Humanities I and II. It was a funny situation. I was wandering around in the halls of Columbia trying to get forms signed for the Ph.D. program, when the head of the English Department, sweating profusely, accosted me. "Hart," he said, "do you want to teach half-time." I said yes. It turned out that the section of Humanities I was to teach had already met twice ... without a teacher. It was a Monday, Wednesday, Friday class, and this was Thursday. Tomorrow, I had to teach the Iliad, which I had never read.

Nevertheless, the Columbia course, still called Humanities I and II, remains at the center of the curriculum there. It is a tremendous experience, both for the students who take it — all Columbia students do — and for the faculty members who teach it. It creates an intellectual community, even among those who disagree. At least they know what questions they are talking about.

Humanities I and II could also be called, if those names are given sufficiently expanded significance, Athens and Jerusalem. Reason and Faith. The drive for universals, and the drive to crystallize the sacred. The great polarities, forced, in major texts, to the extreme.

Humanities I began in the fall term with — traumatic memory of mine — the Iliad of Homer. Then it worked its way through Herodotus, Thucydides, the Greek tragic dramatists, Plato, Aristotle, selections from the Old and New Testaments, Lucretius, Virgil, and Dante. The students knew that they had been through something, and so did the staff teaching the course. It was good for both.

For the spring term, Humanities II began with the Renaissance and the Reformation, which absorbed, commented on, and criticized the earlier experience. The readings included Shakespeare, Rabelais, Cervantes, Montaigne, Spinoza, Milton, Moliere, Swift, Voltaire, Goethe. Then some modern author, most of the time Dostoevski's novel Crime and Punishment, but sometimes Melville or Yeats.

As I say, all freshmen took this course. And, of course, all upper classmen had taken it. It accomplished a number of very important things.

Perhaps most important, it made intelligent conversation possible among undergraduates. They actually had interesting things to talk about with one another, an unusual situation, and, as they experienced it, a cheerful and stimulating one.

Moreover, even the very least of students had the impression that he (Columbia was male) had been somehow dealing with very important matters. And he was right.

But for the good students, even for the fair-to-middling students, the course was a revelation. Lines of Dante, of Homer, especially the most concrete things, will remain forever. Hector is about to leave Troy and fight Achilles. He will lose and he will die. When he says goodbye to his wife and son, the baby is frightened by the plumes on his father's helmet, and begins to cry. A book could be written about that moment: Hector's duty and heroism, his wife's tragedy, Troy's necessity, and the child's cry.

Though to some degree the syllabus in this course had an arbitrary quality — you could read the Odyssey instead of the Iliad — there can scarcely be any question about the quality of the works in fact dealt with. They represent, though of course they do not exhaust, the best that can be thought and said. As Samuel Johnson wrote in his great essay on Shakespeare: "To works ... of which the excellence is not absolute and definite, but gradual and comparative; to works not raised upon principles demonstrative and scientific, but appealing wholly to observation and experience, no other test can be applied than length of duration and continuance of esteem. What mankind have long possessed they have often examined and compared, and if they persist to value the possession, it is because frequent comparisons have confirmed opinion in its favor." All of the works read in this course had triumphantly passed exactly that test.

Furthermore, the overall narrative of the course, "from Homer to the present," in T. S. Eliot's phrase, contains numerous sub-plots. Plato comments profoundly on Homer, as do Aristotle, Virgil, and Dante. Classical philosophy and Christian history meet and fuse in St. Augustine. Dante makes a majestic synthesis. Swift reverses the meaning of Rabelais, and in the Enlightenment the spirit of the classical universal is reborn in a new context. No student who has read Lucretius believes that materialism and atheism are new things. "Literature," as Van Doren once wrote, "is a means to something bigger than itself; it makes the world available to us as chance and appetite do not."

THE Humanities course at Columbia provided a necessary corrective to the provincialism which seems always on the verge of inundating us. It demonstrated that a powerful history of thought and feeling lies behind the present moment. By providing the students with a common body of knowledge, it liberated them: They had something other than triviality to talk about with one another. It did the same for the faculty, allowing them to transcend in a good way the limits of their professional specialties.

To be sure, a syllabus such as this must be defended from time to time against the charge that it is too "Western." As a matter of fact, the course was so successful at Columbia that such a charge was very seldom made: it would have seemed otiose.

But the charge, nevertheless, can be answered, however impolitely: 1) We belong, after all, to Western civilization, and it therefore seems reasonable to acquaint ourselves with that civilization before examining others; and 2) there is, frankly, the matter of quality, a touchy point, I know. The non-Western world has done some interesting things in the lyric and the narrative, and in some instances it has rich traditions of religious meditation. But there does not appear to be any non- Western equivalent — aesthetically or intellectually — of, say, Dante or Beethoven. There is no African or Asian Shakespeare or Mozart. And certainly nothing comparable to the Western tradition in systematic philosophy. If a Chinese — the most impressive of non-Western cultures — wants to be a philosopher, Confucius and Lao-tse do not take him very far. He must engage Hume, Kant, Wittgenstein. There are very good reasons why this is so, having to do with the creative tension between Athens and Jerusalem which persists in the Western tradition.

Both Princeton and Dartmouth, among others, have established pilot programs in the humanities, several sections in which students read a series of works along the lines described here. At Princeton, the program has been immensely successful, and it will predictably be at Dartmouth.

I believe that we should move with prudent speed to make such a course an important component of the liberal education of every Dartmouth student. For various reasons, our curriculum has become fragmented. It lacks narrative content. The parts are greater than the whole. It sometimes seems to have a weightless quality. The students taking This-and-That 14 and Victim Studies 12 are well aware that they are being had. Is it not time that we got serious about the design and purpose of undergraduate liberal arts education?

Jeffrey Hart '51 returned to teach in theDartmouth English Department in 1963.For the Alumni Magazine he has writtenabout grading and conservatism (being aliberal about the one but not the other); healso is a syndicated newspaper columnistand an editor of National Review.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill -

Article

ArticleSeeker of the Heroic

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80 -

Article

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

ArticleRags to Riches

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Jeffrey Hart

Features

-

Feature

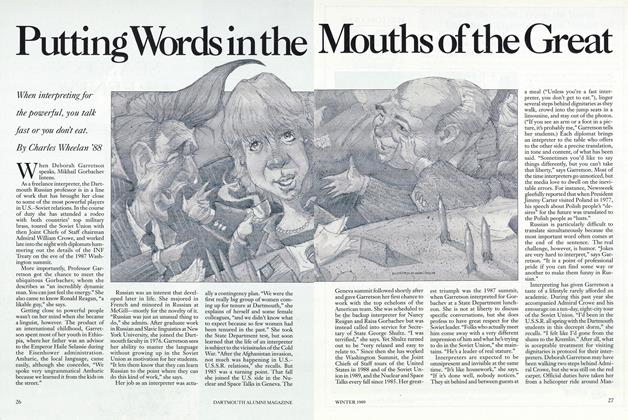

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

JUNE 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

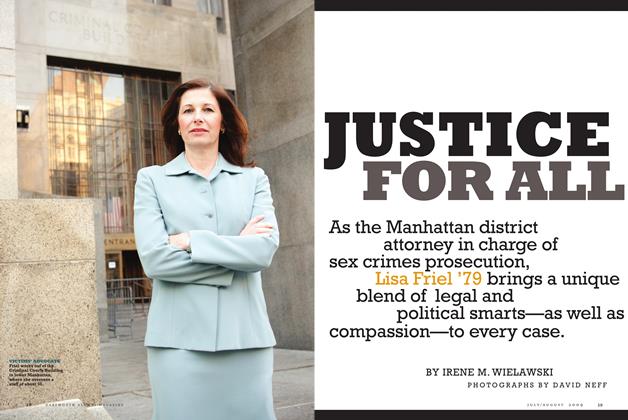

Cover StoryJustice for All

July/Aug 2009 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

FeatureConserver of Life

April 1974 By M.B.R. -

Cover Story

Cover StorySolitary Family

MARCH 1995 By Rabbi Robert Schreibman '57