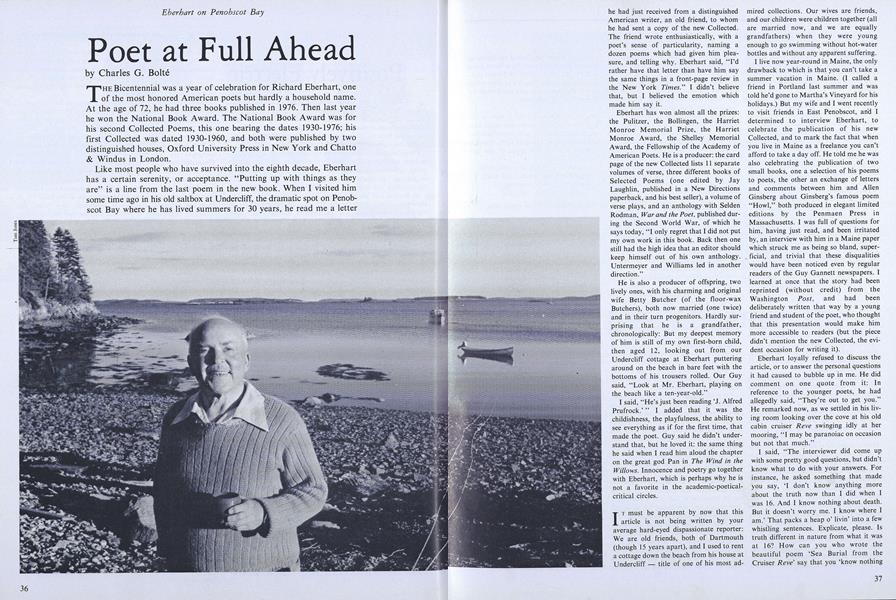

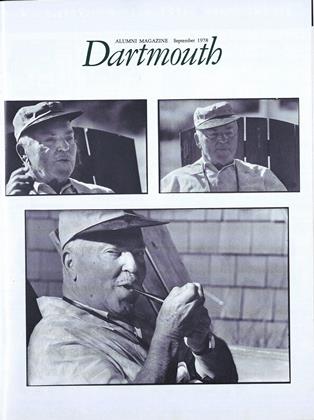

Eberhart on Penobscot Bay

THE Bicentennial was a year of celebration for Richard Eberhart, one of the most honored American poets but hardly a household name. At the age of 72, he had three books published in 1976. Then last year he won the National Book Award. The National Book Award was for his second Collected Poems, this one bearing the dates 1930-1976; his first Collected was dated 1930-1960, and both were published by two distinguished houses, Oxford University Press in New York and Chatto & Windus in London.

Like most people who have survived into the eighth decade, Eberhart has a certain serenity, or acceptance. "Putting up with things as they are" is a line from the last poem in the new book. When I visited him some time ago in his old saltbox at Undercliff, the dramatic spot on Penobscot Bay where he has lived summers for 30 years, he read me a letter he had just received from a distinguished American writer, an old friend, to whom he had sent a copy of the new Collected. The friend wrote enthusiastically, with a poet's sense of particularity, naming a dozen poems which had given him pleasure, and telling why. Eberhart said, "I'd rather have that letter than have him say the same things in a front-page review in the New York Times." I didn't believe that, but I believed the emotion which made him say it.

Eberhart has won almost all the prizes: the Pulitzer, the Bollingen, the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize, the Harriet Monroe Award, the Shelley Memorial Award, the Fellowship of the Academy of American Poets. He is a producer: the card page of the new Collected lists 11 separate volumes of verse, three different books of Selected Poems (one edited by Jay Laughlin, published in a New Directions paperback, and his best seller), a volume of verse plays, and an anthology with Selden Rodman, War and the Poet, published during the Second World War, of which he says today, "I only regret that I did not put my own work in this book. Back then one still had the high idea that an editor should keep himself out of his own anthology. Untermeyer and Williams led in another direction."

He is also a producer of offspring, two lively ones, with his charming and original wife Betty Butcher (of the floor-wax Butchers), both now married (one twice) and in their turn progenitors. Hardly surprising that he is a grandfather, chronologically: But my deepest memory of him is still of my own first-born child, then aged 12, looking out from our Undercliff cottage at Eberhart puttering around on the beach in bare feet with the bottoms of his trousers rolled. Our Guy said, "Look at Mr. Eberhart, playing on the beach like a ten-year-old."

I said, "He's just been reading 'J. Alfred Prufrock.' "I added that it was the childishness, the playfulness, the ability to see everything as if for the first time, that made the poet. Guy said he didn't understand that, but he loved it: the same thing he said when I read him aloud the chapter on the great god Pan in The Wind in theWillows. Innocence and poetry go together with Eberhart, which is perhaps why he is not a favorite in the academic-poeticalcritical circles.

It must be apparent by now that this article is not being written by your average hard-eyed dispassionate reporter: We are old friends, both of Dartmouth (though 15 years apart), and I used to rent a cottage down the beach from his house at Undercliff - title of one of his most admired collections. Our wives are friends, and our children were children together (all are married now, and we are equally grandfathers) when they were young enough to go swimming without hot-water bottles and without any apparent suffering.

I live now year-round in Maine, the only drawback to which is that you can't take a summer vacation in Maine. (I called a friend in Portland last summer and was told he'd gone to Martha's Vineyard for his holidays.) But my wife and I went recently to visit friends in East Penobscot, and I determined to interview Eberhart, to celebrate the publication of his new Collected, and to mark the fact that when you live in Maine as a freelance you can't afford to take a day off. He told me he was also celebrating the publication of two small books, one a selection of his poems to poets, the other an exchange of letters and comments between him and Allen Ginsberg about Ginsberg's famous poem "Howl," both produced in elegant limited editions by the Penmaen Press in Massachusetts. I was full of questions for him, having just read, and been irritated by, an interview with him in a Maine paper which struck me as being so bland, superficial, and trivial that these disqualities would have been noticed even by regular readers of the Guy Gannett newspapers. I learned at once that the story had been reprinted (without credit) from the Washington Post, and had been deliberately written that way by a young friend and student of the poet, who thought that this presentation would make him more accessible to readers (but the piece didn't mention the new Collected, the evident occasion for writing it).

Eberhart loyally refused to discuss the article, or to answer the personal questions it had caused to bubble up in me. He did comment on one quote from it: In reference to the younger poets, he had allegedly said, "They're out to get you." He remarked now, as we settled in his living room looking over the cove at his old cabin cruiser Reve swinging idly at her mooring, "I may be paranoiac on occasion but not that much."

I said, "The interviewer did come up with some pretty good questions, but didn't know what to do with your answers. For instance, he asked something that made you say, 'I don't know anything more about the truth now than I did when I was 16. And I know nothing about death. But it doesn't worry me. I know where I am.' That packs a heap o' livin' into a few whistling sentences. Explicate, please. Is truth different in nature from what it was at 16? How can you who wrote the beautiful poem 'Sea Burial from the Cruiser Reve' say that you 'know nothing about death'? And the last line is simply tremendous: 'I know where I am.' How did you find out where you are, when did you find it out, and where do you in fact think you are?"

"When I was 16 I knew that I would have to die but knew nothing about death in the sense that nobody can know anything about it until he has experienced it. My father and mother, or my grandparents, have not come back to tell me how it was. Thus I knew as much about it at 16 as I do at 72. The great enigma is that if death is nothingness the minute it comes we know nothing about it either. This is not to say that mankind has not studied the subject endlessly. It is one of the great topics for poetry. We know much about it rationally as a fact on which to discourse."

"What about truth?"

"Who can say? I like Plato because he erected Eternal Types against which to measure reality. Aristotle, the scientist, measured the world, flowers, trees, etc., but being scientific thought measurement was all."

"And what about who you are? Does it have something to do with place? Where do most of the poems come from? - Maine, Boston where you worked for the Butcher Polish Company, Dartmouth?" (Eberhart, Class of 1926, has been at Dartmouth 22 years, succeeding Robert Frost as poet-in- residence - though neither held the official title. Nine years ago the age of mandatory retirement came and went; year after year the English Department renews his teaching contract.)

Eberhart said, "As to place and place poetry, I have a poem 'The Place,' which didn't get into the new Collected but is in the old one, which says, 'my flesh is/Poetry's environment.' This means what it says and was said because I have written all my life regardless of where I was, whether in Minnesota, New Hampshire, Maine, or any other state. It is curious that I have written quite a number of poems about the sea although I never saw it until I was over 20. If I had stayed in Minnesota would I have written poems about lakes?

"When I joined World War II friends said that that will be the end of your poetry, but it wasn't. When I went into business in 1946 they said that that will be the end of your poetry, but it wasn't. When I went into university teaching they assumed that poetry would go on, which it did. My point is that place for me is the subjective place of my being."

We talked about his early life: boyhood in a Minnesota small town; recruited for Dartmouth when President Ernest Martin Hopkins was turning it from a New England into a national college (never heard of Harvard then, would have gone if he had); Cambridge after Dartmouth because most Americans who went abroad went to Oxford and he wanted to be different; student there of the formidable critic F. R. Leavis, friend of I. A. Richards and William Empson; believer then that criticism was "a higher thing" than creating; guest of Yaddo three times and now on its board; loves the Century Club in New York but seldom goes; member of the Bollingen jury who had the wit to say "Why don't we give it to Frost?" who dying at 89 had never had either the Bollingen or the Nobel (Eberhart was elected to phone the old man, who said, "What will I do with the money?" and died a week later); whose own Bollingen jumped the sales of his Selected; who still wants to write a poem about the greatest whale in the world; who wrote his own epitaph:

Here lies Richard EberhartWhen he ended he thought he was aboutto start.

He also wrote "The Groundhog" in 20 minutes, a poem which seems likely to stick for as long as poems in English are read. Once he was tutor to the son of King Prajadhipok of Siam, whom he celebrated in the marvelously comic poem, "The Rape of the Cataract." He showed me the unpublished transcript of an interview in which he talked poems casually:

"We have carbon atoms in our kneecap that are eternal and they will be there when our bones are in the earth."

"It must be that the caveman saw the actual sun and the actual moon and when he saw the sun rise in the morning perhaps he let out joyful cries and perhaps that was the first lyrical utterance; when his baby was killed or his mate was killed he felt sad and he lowered his voice and perhaps that was the first eulogy or first death poem."

He said, "I get more radical as I get older."

He talked about the poet's audience, saying that the poet does not in fact write to an audience at all: "It is the poet's prerogative and entrancing job to search out and find the genius of the language. Let any read who will, now or in the future. The poet must discover this uniqueness in verbal expression, the unique build of a phrase, a line, a sentence, a stanza, an entire poem, or any two words rubbing together. Great poets refresh the language with great poems. By finding out the secret heart of expression poets have found out a secret of the heart of man, the former coming from the latter. This is why their works stay in the memory of men and women for generations and centuries."

NE of the marks of a poet is the ability to write memorable single lines which simultaneously compress experience and illuminate it. Here are three, found at random in only five pages of the new Collected:

I stand in my times as a snowflakeWhenever I see beauty I see deathBut for the poet's intervention,which is to save the world.

And this couplet, a few pages later:

I am that vile worm of SatanSent to kill the beautiful.

This is from "The Assassin," in which Eberhart imagined himself into Lee Harvey Oswald; he worried that the publisher's deletion of reference to Kennedy from the title would leave the reader unaware of the reference. I told him not to worry.

In his complaint to Allen Ginsberg about the poem "Howl," Eberhart wrote, "It doesn't tell me how to live." Eberhart's poetry, by indirection, does just that. The poetry shows him to be a member of E. M. Forster's aristocracy: "the aristocracy of the sensitive, the considerate, and the plucky." Forster's epigraph to his great novel Howards End is two words: "Only connect." Eberhart is still connecting. He is chronologically an "elder poet" (so he calls himself: He liked William Cole's saying of him in the Saturday Review, "It is difficult to think of Richard Eberhart as an 'older poet.' He was born in 1904, so I guess he qualifies, but he possesses such ebullience and produces so steadily, it seems as though he has shucked off old age"). He is.extraordinarily robust, an outdoorsman, sailor, collector of mussels from slippery Maine rocks at half-tide, and will probably outlive most of us who are younger but within hailing distance. He will go on producing, healthy as he is, and full of juices, another old wizard as were Frost and Yeats. It is a pleasure to live in same century with him.

Besides writing freelance in Maine (where"you can't afford to take a day off'),Charles Boltè '41 is editor of The American Oxonian, journal of the Association of American Rhodes Scholars.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Company of Stretchers

September 1978 By Cay Wieboldt -

Feature

FeatureTHE RIVER and THE DAMS

September 1978 -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleDickey-Lincoln: Who wants it? Who needs it?

September 1978 By Greg Hines -

Article

Article'A Spirit of Fire and Air'

September 1978 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Article

ArticleTennis: The Coach Wore New Underwear

September 1978 By CHRIS CLARK