A visitor entering Elisabeth Appleton's office in Bartlett Hall has difficulty realizing that it is center of dance at Dartmouth. Professor Appleton seems more like a reclusive scholar than the College's only full-time dance instructor. She is reserved to the point of being shy and manifests none of the bombast sometimes associated with an "artistic" personality. This impression of shyness lasts only until she begins to talk about dance. Then Appleton breaks into an engaging exuberance that makes the listener, no matter how uncoordinated, want to try dance himself. "I like helping people to feel the joy of moving," she suddenly declares. "I like teaching beginners, and I like teaching experienced dancers to refine their movements."

The opportunity to appreciate this joy is relatively new for students at Dartmouth. The College has only offered modern dance for credit since 1969. The course proved sufficiently popular to add an advanced class in 1971 and a dance history class in 1974. Dartmouth was actually ahead of the rest of the Ivies in first offering dance for credit and first offering a dance history class, but Appleton believes the change was long overdue.

"Nowadays," she says, "you have students coming to Dartmouth who are quite good and who expect that there will be a complete dance program." The Drama Department, of which Appleton is a part, is currently moving toward creation of a dance concentration within the drama major, but Appleton points out that there already have been Dartmouth students who put together full dance majors by taking advantage of dance courses offered elsewhere during exchange terms.

What has caused this upsurge in the popularity of dance? Appleton thinks it is part of a trend that for various reasons has been developing for the past five or ten years. She cites a waning of the stigma against dance as effeminate. She feels that popular culture has rebelled against an increasingly intellectualized world and gives as examples of this rebellion the popularity of yoga and other disciplines that emphasize body awareness. "These days we all crave something physical," she says. "There is a need to move." Another factor in the rise of dance has been the defection of several premier Russian ballet stars. Because the performances of Nureyev, Baryshinikov, and others have been so highly publicized, unusually large American audiences have experienced the true and ultimate beauty of dance. Appleton also points to the role of the touring program of the National Endowment for the Arts, which has taken performers and teachers to theaters and schools across the country - to "the people."

At Dartmouth, the rise of dance has coincided pretty much with the national trend, but it has had its special problems. When Hopkins Center was in its planning stages, the idea of building dance studios never even occurred to the planners. Dartmouth was all male then, and there was simply no demand for dance facilities. Ironically, the building of the Hop created a need for facilities by making possible frequent large dramatic productions that require choreography and experienced dancers. This and the coming of coeducation created a need that was not being filled. It is not surprising, therefore, that current plans for expansion of the Hop include space for dance studios.

For Appleton, the facilities will come none too soon. Last year, because of the demand, the Drama Department initiated dance classes for the first time in the winter. The classes were held in Webster Hall (as are all the dance classes), and Appleton remembers the term with trepidation: "It was murder. So dark — and boy, was it cold." There are other nonseasonal but inherent problems with Webster. The stage floor requires matting to guard against splinters, and the makeshift studio consisting of bars, mirror, and mats must be stored away any time another student group needs to use the facility, which is often.

Still, amidst these humble and even spartan conditions, Dartmouth students manage to learn modern dance and sometimes to excel at it. Consider Pilobolus, the modern dance group that began with four inexperienced, male, Dartmouth students taking a beginning dance class much like the ones Elisabeth Appleton currently teaches. The group put together a composition for a 12:30 Rep at the Hop, and the piece was received with wild enthusiasm. The rest is history. Today Pilobolus is regarded by critics and fans as easily the most innovative and exciting thing to happen to modern dance in years. Appleton hasn't been the mentor for a Pilobolus yet, but her students are being steeped in technique — in balance, rhythm, coordination. For this reason the courses in years past have been popular with football players who felt that their play was improved by the class and their susceptibility to injury lessened by all the stretching required of dance students.

Evidently, students are often surprised by just how much they are able to absorb. At one class a student commented that he hadn't realized how much he'd learned until he watched a newcomer bumbling about all over the stage. This ability to learn does not surprise Appleton at all. "Your body is smart if you'll just let it be," she declares, but adds that Dartmouth students sometimes try to think too much. To dance, she says, "You don't think about it — you just let the body do it." She finds that it is easier for children to start right off dancing because they don't intellectualize or ruminate over the movement. Nevertheless, Appleton considers teaching Dartmouth students enjoyable because they don't mind making the effort to learn how to dance. "Dartmouth students are in general athletic," she observes. "They like hard work. The more I push them, the more they like it."

Appleton is no stranger to hard work herself. She started dancing at the age of seven and continued with it through high school. Instead of going straight to college, she danced with the Chicago Opera Ballet for a year. Subsequently, she earned her undergraduate degree at Radcliffe and then obtained a master's degree in dance education at Stanford. From Stanford, Appleton came to Hanover, where she began teaching four years ago. Besides teaching, she also frequently choreographs productions at the Hop.

At the moment, Appleton is involved with Seven Deadly Sins, a Bertolt Brecht- Kurt Weill drama done only in song and dance. The choreography for the production is particularly difficult because the action is carried primarily by dance. Asked how a choreographer begins to formulate the dances for a production, she says that there are two places to begin: the music or the story. Most dance begins with the music, but not always. She points to Pilobolus as an example of a group that formulates its routines ("Say piece," she admonishes — " 'routine' sounds too much like 'show business' ") and brings in music later to fit the piece. Not only is their music tailored to their movement, but it also evolves with it. As Pilobolus got better and faster at its compositions, the music was changed as well. (Pilobolus' music, incidentally, was first composed by Music Professor Jon Appleton, co-inventor of the Synclavier and husband of Elisabeth.) "But generally," Elisabeth Appleton comments, "choreography begins with the music." From there, a choreographer might look at the locale of the action in the drama, begin with appropriate folk dances, and add theatrics and elaboration gradually. "If nothing else works," she says, "you just move with the mood of the music."

Moving with the mood of the music seems to be what modern dance is all about, and Appleton's students strive to learn that within the fairly challenging framework of her beginning dance course. In the past, dance was offered on a credit/no credit basis, but it is now graded and consequently a little more demanding. Feeling that a standard three hours a week is not enough, Appleton has the class meet four times a week for a total of seven hours. Unexcused absences and early departures from class entail a grade penalty. The students read books on dance, but instead of doing papers they present original compositions every Thursday in small groups or solo.

The class period can only be described as rigorous. One might expect that instruction would take the form of leisurely demonstration followed by repetition on the part of the students, with plenty of time for practice and perfection. Instead, the exuberance that Appleton displays when she talks about dance is transformed into action. The class begins when the students — equal numbers of men and women — follow Appleton in a series of stretching exercises that for a beginner in his first day seem akin to experiencing the torture rack. An accompanist plays improvisational melodies on the side. They are smooth or discordant, sad or joyful according to the exercise. The exercises go on for half an hour, and then Appleton begins in earnest what will prove to be an hour-long, complicated game of Monkey See-Monkey Do.

At this point the observer begins to realize that the one thing the class has not done is rest. The students are beaded with sweat, but as soon as they finish one routine, Appleton starts another. This grueling pace is intentional; she wants to fit as much work as possible into class time and remarks, "It's important not to give people time to think when they're learning dance." On she leads her students through kicks, plies, and bends. Amid the music and the soft grunts of straining students she intersperses helpful admonishments of "Grow taller — feel yourself grow taller" or "Point those toes — keep that leg straight" or "Get your weight on the balls of your feet."

Finally, with a half hour left in the class period and still no rest, Appleton gathers the class into a corner of the stage to do leaps and kicks. Two by two the students progress across the stage with varying degrees of aerial precision. After several different leaps and with one minute remaining in the period, Appleton announces that the last exercise is upon them. A few students look relieved. "Come on," she says, looking around brightly, "one, two, three, four. ..."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

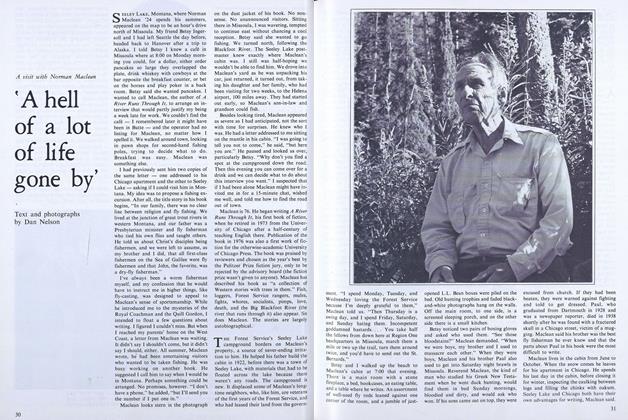

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

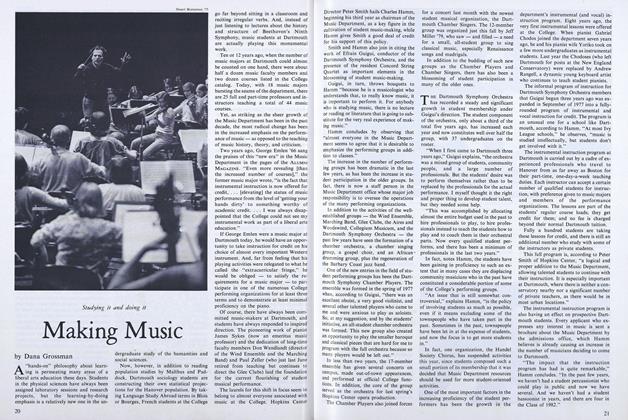

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Article

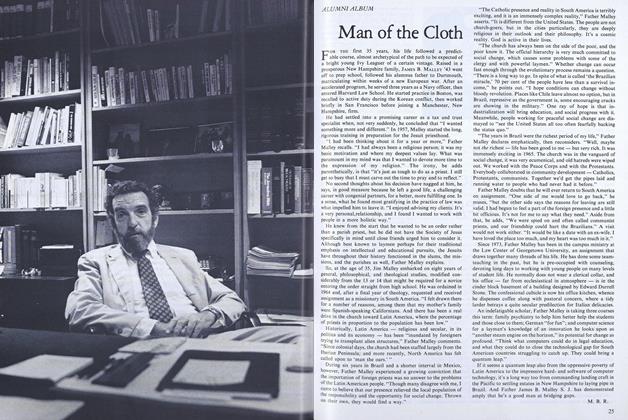

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWhy the NCAA

November 1978 By SEAVER PETERS '54

Article

-

Article

ArticleJ. P. BOWER '22 TO COACH WILLIAMS BASEBALL TEAM

November, 1025 -

Article

ArticleAdmissions Policy Misrepresented

October 1945 -

Article

ArticleOn Tune 1, The Rev. Telfer Mook '38

December 1960 -

Article

ArticleWinter in Colorado

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Article

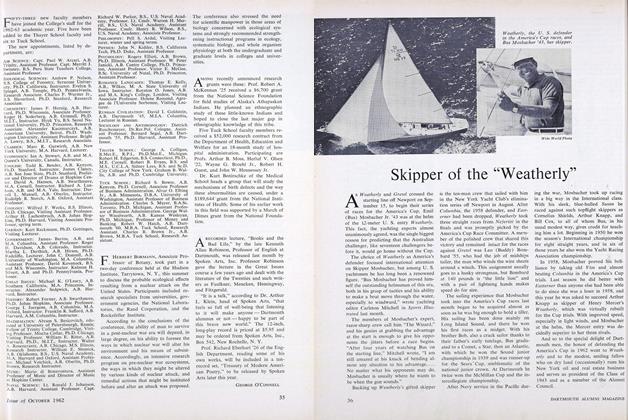

ArticleTHE FACULTY

OCTOBER 1962 By George O’Connell -

Article

ArticleA Leader of Gay Journalists

October 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93