If you're wondering whatever happened to the Peace Corps, Keeping Kennedy's Promise is the book to read.

"More than 65,000 Peace Corps Volunteers have served abroad," Lowther and Lucas write. "Many have had a real job to do; many have been qualified to do those jobs; and many have had the cultural curiosity, language facility, and unwavering commitment to do those jobs well in spite of the often intimidating physical and psychological challenge."

"Many though they are," the authors add, "they are the exceptions. For the great majority of volunteers have been sent abroad without sufficient skill, without sufficient language ability, without sufficient cultural awareness - and without a clear or critical job assignment. They are the unmet hope of the Peace Corps."

Many will disagree that most volunteers have been floundering failures. For people like me who still hold romantic notions about Peace Corps, this is not a comfortable book to read. Many criticisms contradict my personal experience. Nevertheless, no one can ignore two authors who are among the very few to live in Peace Corps Washington over several generations of directors - a unique perspective reinforced with a variety of agency records.

With sensitivity and penetrating insight, Lowther and Lucas construct a credible thesis that competent volunteers were an exception. The authors' intimacy with Peace Corps, however, casts some shadows on their conclusions. One wonders if they were too close, too critical.

Lowther and Lucas reveal no partisan prejudice in ripping away fancy wrapping in search of truth. They examine Shriver as coldly as Balzano. Remember Balzano? Of course not, and that's one reason many wonder if Peace Corps still exists.

With strong, clean writing, the authors tell how Shriver's decision to make Peace Corps the disco of government fizzled when volunteers crashed into each other On every continent. They write about teachers who couldn't teach, community developers who confused motion with action, volunteers in Paradise who quit before they started (Paradise was Peace Corps marketing for Micronesia - one out of four didn't finish a two-year program; one out of nine transferred). Displaying a journalist's sense of accuracy and record, the authors carefully document conceptual blunders, administrative incompetence, and political neglect.

In the end, they raise central questions: "Can the Peace Corps teach a passion for people? Can it teach them to love and to be loved? Can it show teachers why they must learn from their students? Can it convince agents of change that they must themselves be changed in consequence?" Yet despite affirming the need for soul, they conclude that Peace Corps "is not a cultural sandbox in which young Americans may outgrow their ignorance of the world."

They give singular priority to meeting the development needs of the Third World: "Unless the Peace Corps is transformed into a respected source of technical assistance, it should humbly fold its tent." Do they forget that another of Kennedy's legislated mandates is to promote peace, that perhaps a people-to-people program is equally valid and ultimately as effective as providing technical assistance?

Peace Corps is at another crossroad. Should the agency split from Action, the holding company for several also-ran social programs? Should Peace Corps become a reserve for technicians? Is community development a misconceived plan "to remake the world"? Is there a welcome mat for Dartmouth graduates - classified traditionally as B.A. generalists?

Whatever the answers, Keeping Kennedy'sPromise will help us decide. As for Lowther and Lucas, they shared Kennedy's dream, and they state clearly that the unmet hope is worth redeeming.

KEEPING KENNEDY'S PROMISEBy Kevin Lowther '63 and C. P. LucasWestview, 1978. 153 pp. $10.00

The first former Peace Corps volunteer appointed by the President to the National AdvisoryCouncil to the Peace Corps, Dawley isalso a founding trustee of IF, a nationalorganization of former volunteers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

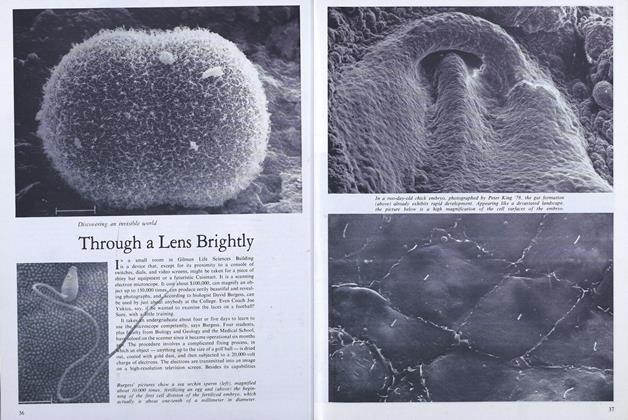

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

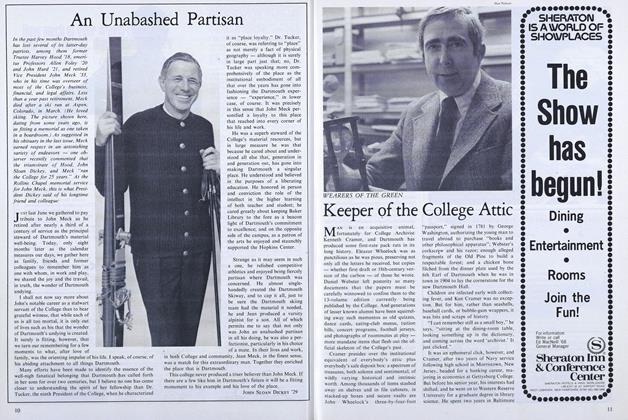

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD

DAVID DAWLEY '63

Books

-

Books

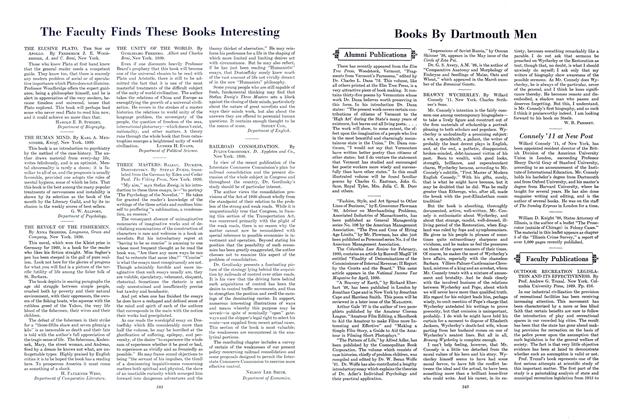

BooksJohn C. Holme '30

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksThere has recently appeared from the Elm Tree Press

JUNE 1930 -

Books

BooksTHE STRUMPET SEA

June 1938 By E. P. Kelly '06. -

Books

BooksTHE MOST AMAZING BUT TRUE.

JUNE 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLET THEM EAT PROMISES: THE POLITICS OF HUNGER IN AMERICA

JULY 1970 By MICHAEL P. SMITH -

Books

BooksCharles Darwin Adams: Demosthenes and His Influence

AUGUST, 1927 By William Stuart Messer, Edwin J. Bartlett