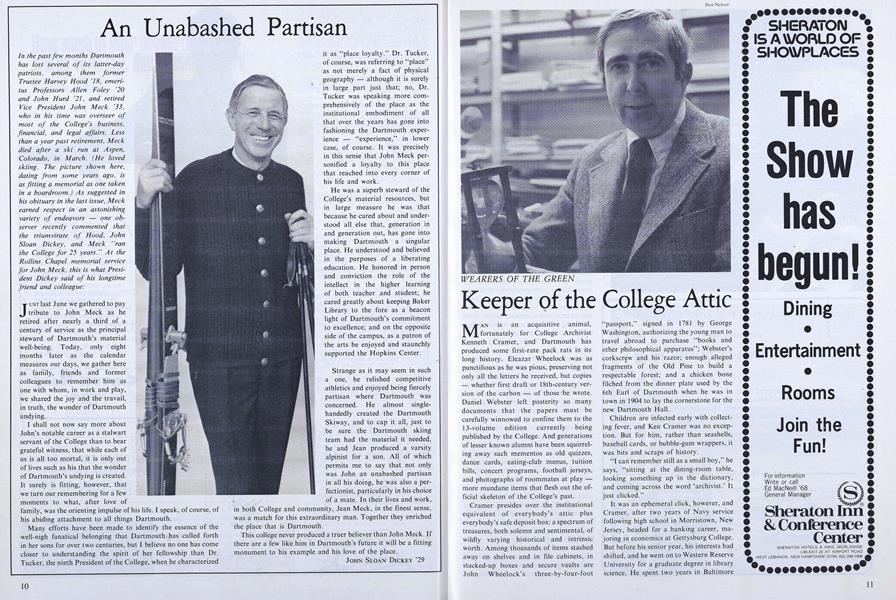

MAN is an acquisitive animal, fortunately for College Archivist Kenneth Cramer, and Dartmouth has produced some first-rate pack rats in its long history. Eleazar Wheelock was as punctilious as he was pious, preserving not only all the letters he received, but copies - whether first draft or 18th-century version of the carbon - of those he wrote. Daniel Webster left posterity so many documents that the papers must be carefully winnowed to confine them to the 13-volume edition currently being published by the College. And generations of lesser known alumni have been squirreling away such mementos as old quizzes, dance cards, eating-club menus, tuition bills, concert programs, football jerseys, and photographs of roommates at play - more mundane items that flesh out the official skeleton of the College's past.

Cramer presides over the institutional equivalent of everybody's attic plus everybody's safe deposit box: a spectrum of treasures, both solemn and sentimental, of wildly varying historical and intrinsic worth. Among thousands of items stashed away on shelves and in file cabinets, in stacked-up boxes and secure vaults are John Wheelock's three-by-four-foot "passport," signed in 1781 by George Washington, authorizing the young man to travel abroad to purchase "books and other philosophical apparatus"; Webster's corkscrew and his razor; enough alleged fragments of the Old Pine to build a respectable forest; and a chicken bone filched from the dinner plate used by the 6th Earl of Dartmouth when he was in town in 1904 to lay the cornerstone for the new Dartmouth Hall.

Children are infected early with collecting fever, and Ken Cramer was no exception. But for him, rather than seashells, baseball cards, or bubble-gum wrappers, it was bits and scraps of history.

"I can remember still as a small boy," he says, "sitting at the dining-room table, looking something up in the dictionary, and coming across the word 'archivist.' It just clicked."

It was an ephemeral click, however, and Cramer, after two years of Navy service following high school in Morristown, New Jersey, headed for a banking career, majoring in economics at Gettysburg College. But before his senior year, his interests had shifted, and he went on to Western Reserve University for a graduate degree in library science. He spent two years in Baltimore with the Enoch Pratt Free Library, then came to Dartmouth in 1955 to work in the reference department at Baker. The near proximity of College Archives set the old click to clicking again, and Cramer asked to spend part-time assisting Archivist Ethel Martin. He left the College briefly, for a year in special collections at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, then returned after a special course at the National Archives in Washington - the only professional archival course then available - to succeed Martin on her retirement.

"From the Wheelock papers on through World War I," Cramer reports, "official College records are quite complete. Dartmouth has been fortunate in never having had a serious fire in a building where historical papers were stored. As far as we know, little archive material was destroyed when Dartmouth Hall burned." He speculates sadly, however, on how much of the color and the deliberative process has been lost as thoughtful long-hand correspondence has given way to the Dictaphone and telephone transactions.

"One area in which we are deficient," he adds, "is faculty papers." In this category he includes not only course syllabi and examination papers, but articles, lecture notes, grade books, correspondence - "even family correspondence which helps to show the other side of the man." One reason they are not as complete as they should be, Cramer explains, is that "a lot of faculty members tend to belittle their own work and the importance of what they're doing. Others simply procrastinate." He cites, as a poignant and timely example, Al Foley who, at Cramer's prompting, had given some of his papers before his sudden death in February, but nowhere near the volume that archives would like to preserve. "The best time to go after them," Cramer muses, "is probably when they retire and are cleaning things out."

A small staff - two assistants and a shared secretary - and some general responsibilities in special collections, of which archives are a part, leave less time than Cramer might wish for missionary work among the faculty and the departments. He calls it "getting out in the field": helping academic and administrative personnel decide what should and what should not be kept. Some institutions, he says, save a copy of "everything that comes off a mimeograph machine," but for reasons of efficiency and space Dartmouth is considerably more selective.

"It's hard to know what to collect," Cramer admits. Official records, of course, and papers of distinguished alumni and College personnel, departmental documents, and all College publications. It's usually easiest for him and his staff if departments turn over everything they have. "Then we can cull it out in our own bailiwick," he says. The Dartmouth Outing Club, for instance, has just presented archives with some 30 cartons and ten portfolios of papers, including registers from all the DOC cabins, maps, and old Carnival posters. As Cramer's assistant works with the collection, she will sort out duplicates, hopelessly illegible papers, and other articles of dubious historical value. At the same time, she may well be going through the same procedure with another collection that has been packed away on a back shelf perhaps for decades. "Some collections have been here for 100 years without being sorted or catalogued," Cramer notes. "We're trying to take care of the backlog by working simultaneously on one old set of papers and one recent acquisition. In time, we hope to get caught up."

Alumni are a rich source of archive material, particularly of the personal artifacts that contribute human flavor to the historical substance, adding immeasurably to our understanding of the everyday life of the College. In addition to periodic questionnaires and news items about each alumnus, accumulated over his or her lifetime by the Alumni Records Office and ultimately going to archives, individuals donate a colorful assortment of memorabilia. Of special interest are scrapbooks - the "mem books" which, to Cramer's distress, seem to have gone out of style about the 1930s. It was one of these, presented by an alumnus who earned part of his way through college as a waiter, that yielded not only the 6th Earl's chicken bone, but a mustard spoon from the banquet table and.the napkin used to mop His Lordship's moustache. Student correspondence, particularly wartime letters from the front, and all manner of personal photographs are highly prized. A valuable addition to a collection of some two dozen senior canes was Ernest Martin Hopkins' own, presented recently by his daughter Ann Hopkins Spahr.

Alumni publications - one of two categories in archives' book collection, the other being historical works about the College and the local area - are near complete for the first 150 years. But, as Dartmouth authors grow more prolific and more specialized and the cost of accessioning a book soars - it's $10 or $12 a title nowadays - the archives can no longer afford to solicit or to keep all books and articles written by alumni. For those that do find their way into the alumni collection, "we bend toward the literary," Cramer concedes.

College Archives is the repository, though not the instigator, of a relatively new vehicle for retaining historical evidence. For the past few years, the College has been systematically assembling an oral history, preserving personal recollections of events great and small in Dartmouth's recent past through taperecorded interviews with faculty members and administrators. These will be entrusted to Cramer's stewardship, along with conversations recorded some years back with such personages as President Hopkins and poet Robert Frost.

Such day-in, day-out immersion in the stuff of the College's past might make even the alumnus most sealed of the tribe of Eleazar blanch, but Cramer claims not to mind. Though not a Dartmouth man, "I've been here so long, I feel like one," he says. "From the time I first came, I felt absorbed by the College and the community."

For a change of pace, he has his own "special collection": anything and everything about the Scottish Orkney and Shetland Islands and the Danish Faroes, which curve in a northwesterly arc above the northern tip of Scotland. Cramer's hobby has its complex origins in a Danish great grandfather who emigrated from the Old World to the Danish West Indies, now the U.S. Virgin Islands; in another early encounter between an incorrigibly inquisitive child and an atlas; and in a young sailor's passage through a strangely calm Pentland Firth, which links the North Sea and the Atlantic, and the sight of the islands stretching out "like never-never land" in the late evening twilight. Cramer subscribes to the island newspapers, follows their local politics, reads omnivorously of their history, corresponds with some of their citizens, and worries about the effect North Sea oil may have on their culture. He hopes to return soon, for a fourth visit, to see for himself.

For an archivist, who must be both acquisitive and inquisitive, who must have the patience for a job that can by definition never be complete, Dartmouth holds undeniable attraction. As an institution that "may be unique," Cramer says, as the only colonial college never to have closed nor moved even during the Revolution, it has a long, rich heritage. With a Dartmouth family that regards itself as unique in devotion, it also has a tantalizing collective family attic, bursting with who-knows-what undiscovered treasures: perhaps some lively correspondence between Governor Wentworth and George III about a suitable symbol for the College - or even a sliver of the goalpost from the 1935 Yale game.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

May 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

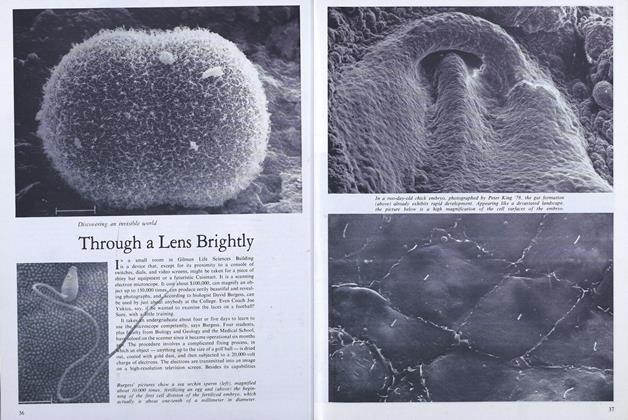

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD -

Article

ArticleA Household Word Among the Voiceless

May 1978 By M.B.R.

M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMEETING OF THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1938 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Contributors

December 1956 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1972 By BRUCE KIMBALL '73 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

DECEMBER 1970 By CHRISTOPHER CROSBY '71 -

Article

ArticleAbout Twenty-Five Years Ago

June 1936 By Warde Wilkins '13