Tweaked from the air, as it were

Now is the season of the whelm, the wedge, the well, the wax, the waft, the wane, the wasting, the warp, and the was. And many a Dartmouth lad and lass you will see wristing their way into them on the College Green.

This alliterative accumulation of words beginning with the 23rd letter of the alphabet is not some arcane incantation. It is a listing of the six periods of flight of the Frisbee, that plastic dish that has been taken up by the collegiate set (among many others) in increasing numbers since 1948 when Walter Frederick Morrison, the son of the inventor of the automobile sealedbeam headlight, came up with an illumination of his own - the modern, or plastic, Frisbee.

(Indeed, so much has the Frisbee caught on in colleges that Dartmouth this spring has fielded its first Frisbee team in competition with other eastern wrist-ful powers.)

Most devotees of Frisbee who have done even the most rudimentary research into the subject are prone to accept the fact of Morrison's invention and let it go at that. Dr. Stancil E. D. Johnson, a psychiatrist out of Pacific Grove, California, and an avid player and historian of the game, is not entirely sure that Morrison is the true inventor of the Frisbee. In his paperback book, starkly entitled Frisbee, Dr. Johnson concedes that Morrison evolved the first plastic Frisbee. But he delves a bit further.

In Bridgeport, Connecticut, Johnson reports, there once existed the Frisbie Pie Company. It existed from the 1870s until 1958 (the building fairly recently housed the Leathermode Sportswear Co., which many think to be a sharp comedown). This baking concern produced a power of pies over the years, reaching a pie pinnacle of 56,000 in 1956.

Moreover, it marketed them in pie tins. The Johnson research claims that Yale students bought the Frisbie pies and, after consuming them, would scale the tins about the New Haven campus. Indeed, Johnson says, the Yalies "would exclaim 'Frisbie' to signal the catcher. And well they might, for a tin Frisbie is something else again to catch."

Now all of this is undoubtedly true. There probably was a Frisbie Pie Co. (Johnson furnishes a photograph of it and even gives its address as 363 Kossuth Street). There almost certainly have been Yale students, although the jury is still out on this. They quite reasonably might have been Frisbie pie-eaters. And they may even have flang Frisbie pie tins about, New Haven being the place it is.

But Johnson has let a central point escape him. And that is: Yale students, ColePorter excepted, have never inventedanything.

No, Johnson didn't go far enough back, although he was on the right track with the Frisbie Pie Co. The Frisbies, as anyone will find out, if he dabbles in Connecticut genealogy, were (and are) a numerous clan. Their origins go back to the earliest days of the Connecticut colony. And, like early and numerous clans, they threw off many shoots.

ONE of these shoots was one Levi Frisbie, son of Elisha and Rachel (Levi) Frisbie, who was born at Branford, Connecticut, hard by New Haven, on April 11, 1748. Levi, disdaining the jejune purlieus of Yale, made the hard journey to the northern wilderness of New Hampshire and, in due time, became a member of the first class, four good men and true, of the fledgling Dartmouth College, in 1771. After studying further with the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock at Hanover, he was ordained a missionary on May 21, 1772.

His mission was to the Delaware Indianson the Muskingum in Ohio. (Or what wasto become Ohio.) He also sermonized for a spell among Indians in Canada and Maine, but the Revolutionary War brought an end to his missioning. He was installed pastor at the First Congregational Church at Ipswich, Massachusetts, February 7, 1776, and spent 30 quiet but fruitful years there before dying in 1806.

Thus the bare bones of Levi Frisbie's career. What has recently come to light has shown that this Congregational divine, stout as he was in patriotism (an "Oration on the Peace of 1783" and'a "Eulogy on the Death of Washington" are among his published works) and devout as he was in his faith, had a light and frolicsome side.

Recently, when a display case was moved in Wilson Museum, a piece of paper, brittle and yellowed with age, slid to the floor. It no doubt would have been swept up by the zealous keepers of that Romanesque pile but for the sheer happenstance that a visiting Irish anthropologist was johnny-on-the-spot.

What the paper was, it turned out, was a memoir of Frisbie's penned for his 25th reunion in 1796 (which never got printed because of the XYZ Affair). Somehow, in the shifting of libraries from Dartmouth Hall to Reed Hall to New Hampshire Hall and goodness-knows-where, the paper became lost.

Careful work by the firm of Flake, Patina and Crumbell, restorers of antiquities, has stabilized the decay of the memoir and such segments as the following are now clearly discernible:

Whilst I was sojourning among the Indians [Frisbie wrote], not long after leaving Hanover Plain and the good Dr. Wheelock, I discovered them to have a fanciful and graceful pastime each year shortly after the sowing season. They would go out into their small fields with large flat platters of woven withes of willow. These were for carrying corn seeds for planting and, to that end, had slightly raised edges all around so that the corn seeds would not spill needlessly upon the ground.

Once the planting was done, and it was always done fairly quickly, for these Indians, not unlike their white brethren, do not fancy the rigors of that task, they fell to play. First one, then another, would take to launching these corn-planting platters into the air, with a curious whirling motion, beginning, as it were, as if they were about to drop the platter behind their backs. But then, with a wondrous, quick, unwinding motion the arm would flash forward from behind and the platter would soar out upon the air.

It would describe curious flights, this plaited utensil, and another member of the planting party, his eyes intent upon it, would nimbly pursue it and, in a moment of surpassing grace, tweak it from the air.

Some of my fellow missionaries thought these performances, which would often last until light failed, to be some form of pagan planting ritual, but I think them to have been merely innocent play, done in childlike gaiety and pleasure.

I brought back with me to Ipswich one of these platters, and my son Levi [later a professor at Harvard and possibly the apostle of this game there] and I have often disported ourselves secretly with it upon the beaches there. ...

Here the memoir becomes patchily indecipherable, but surely the case is clear. Johnson, in his researches among the Frisbie family in Connecticut, simply did not dig deeply enough, a common failing among psychiatrists. But, to give Johnson his due, he was on the right track. Frisbee, in some unaccountable way, has become a variant spelling of the game that the old Dartmouth clergyman discovered among the Indians. (It is not clear from his memoir whether among the Delaware, Maine, or Canadian ones, although one could strongly surmise that it must have been among American, not Canadian, Indians.) And brought back to white civilization, as represented by Ipswich, and perhaps passed down by his son to the Ivy League outpost at Cambridge.

Now that this is known and now that Dartmouth is mounting a team in Frisb(i)ee, it is hoped that there will be a corner of not a foreign, but a Dartmouth, field that will be forever Frisbie. And that Dartmouth lads and lasses, as they launch their modern platters will shout, in honor of that primal classman of theirs, "Come on, man, Levi-Tate."

James L. Farley '42 wrote about studies ofthe Olmec and Dorset Eskimo civilizationsin the January/February issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCould it be that the political animals are hibernating?

May 1978 By Anne Bagamery -

Feature

FeatureCastles in the Clouds

May 1978 By George Hathorn -

Feature

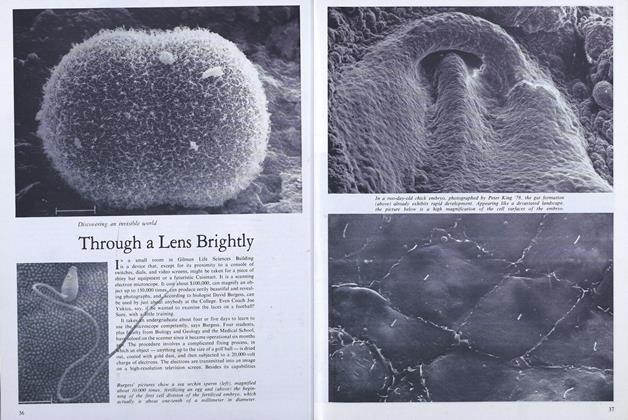

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

May 1978 -

Article

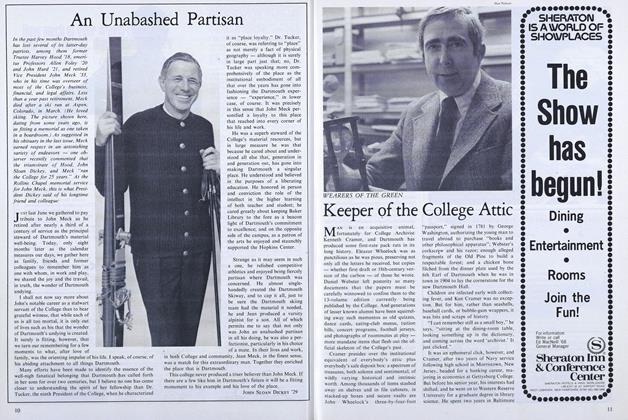

ArticleKeeper of the College Attic

May 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

May 1978 By COREY FORD -

Article

ArticleA Household Word Among the Voiceless

May 1978 By M.B.R.

James L. Farley

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

January 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

October 1949 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

December 1949 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

October 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

April 1948 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

April 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II

Features

-

Feature

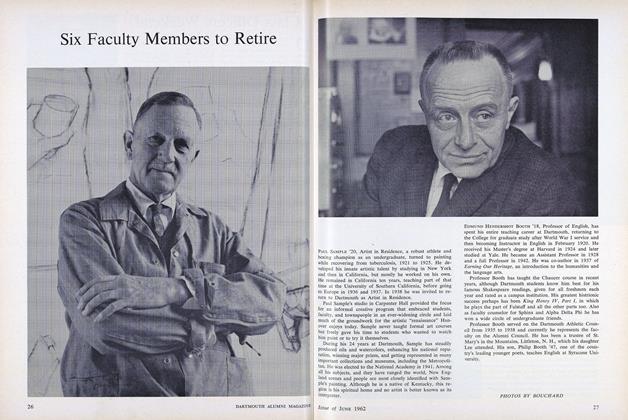

FeatureSix Faculty Members to Retire

June 1962 -

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPRESIDENTIAL SEAT CUSHION

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

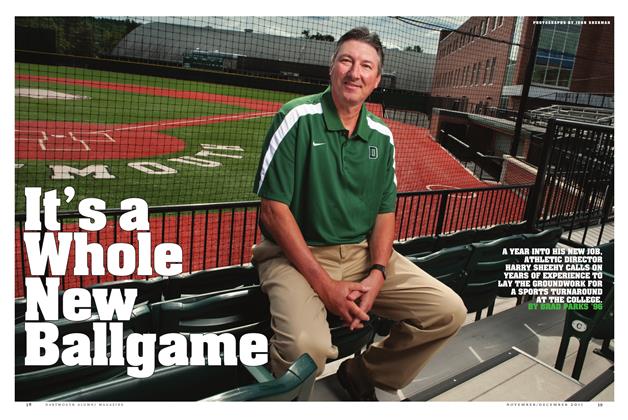

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt’s a Whole New Ballgame

Nov/Dec 2011 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

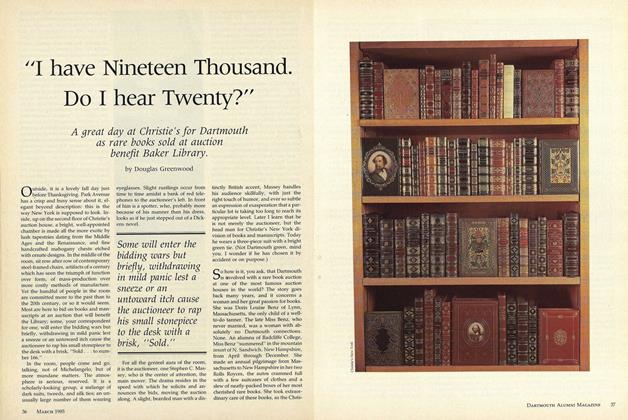

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

MARCH • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

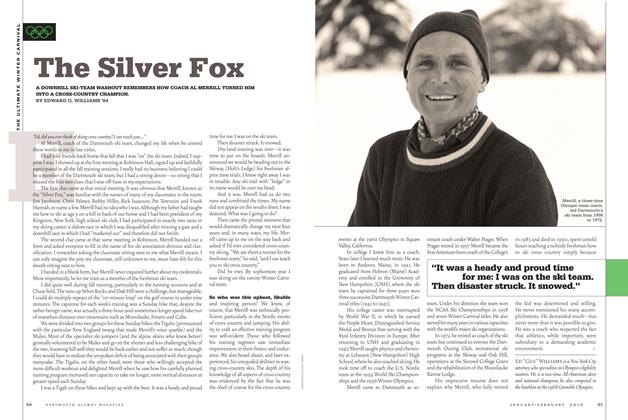

Feature

FeatureThe Silver Fox

Jan/Feb 2010 By EDWARD G. WILLIAMS ’64