Who they are, what they do

At a soapbox-speakers' forum held on the Green a few weeks ago, an assistant professor stood up and addressed a small group of students, a couple of teachers, and about a dozen alumni. He made some suggestions for improvements in academic and social life — the formation of residential colleges (like Yale's) and the institution of eating clubs — then called upon the College, especially the trustees, to accept responsibility for involvement in the solution of social problems, to take "moral stands" on issues beyond those immediately facing Dartmouth.

That view of an educational institution's obligations has become familiar, and the same afternoon one of Dartmouth's senior trustees was asked what he thought of it. He didn't hesitate to say he disagreed "1,000 per cent" with the professor's assessment. "The institution has got to remain an educational institution," the trustee insisted. "It does not have to be at the cutting edge of all these social changes. The claim that we should be responsible in that way is ridiculous."

Dartmouth's trustees always have been expected to set policy for the College and to manage its well-being. That expectation always has included fund-raising — $160 million in the present five-year Campaign for Dartmouth — and stewardship of assets. Trustees at other institutions claim financial management to be their primary — or even their only — responsibility, but at Dartmouth, without attempting to impinge on the administration's role, the trustees maintain a broader interest. They have ultimate responsibility for the College's financial, administrative, and educational affairs.

While their selection is said not to depend on their ability to contribute large amounts of money, and aside from qualities of character and intelligence, most of the trustees are prosperous, important men, active in a variety of civic, professional, and philanthropic affairs. Whereas Dartmouth's trustees once were mostly clergymen, they now are mostly businessmen and lawyers — or both. At Dartmouth and in their careers they have, in general, excelled at being successful: scholar-athletes and leaders in college; law partners and corporation presidents in professional life. While it would not be accurate to say that all were cast from the same mold (one is a teacher, one is black and works for the Ford Foundation, and one — the newest — is a woman), it is fair to say that despite differences in personality and style, they are for the most part men who can easily understand one another, men who share similar values, and, as they all point out, men who share an affection for and commitment to Dartmouth.

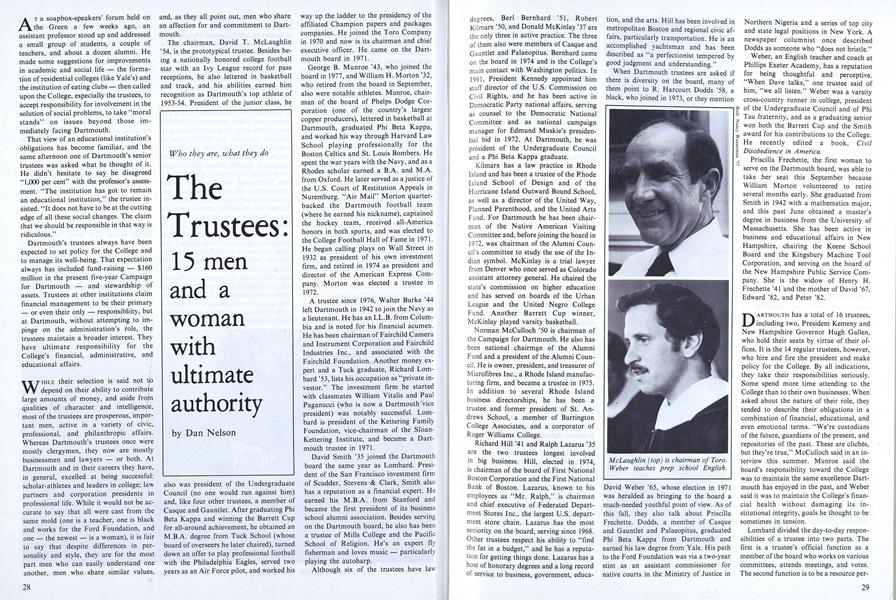

The chairman, David T. McLaughlin '54, is the prototypical trustee. Besides being a nationally honored college football star with an Ivy League record for pass receptions, he also lettered in basketball and track, and his abilities earned him recognition as Dartmouth's top athlete of 1953-54. President of the junior class, he also was president of the Undergraduate Council (no one would run against him) and, like four other trustees, a member of Casque and Gauntlet. After graduating Phi Beta Kappa and winning the Barrett Cup for all-around achievement, he obtained an M.B.A. degree from Tuck School (whose board of overseers he later chaired), turned down an offer to play professional football with the Philadelphia Eagles, served two years as an Air Force pilot, and worked his way up the ladder to the presidency of the affiliated Champion papers and packages companies. He joined the Toro Company in 1970 and now is its chairman and chief executive officer. He came on the Dartmouth board in 1971.

George B. Munroe '43, who joined the board in 1977, and William H. Morton '32, who retired from the board in September, also were notable athletes. Munroe, chairman of the board of Phelps Dodge Corporation (one of the country's largest copper producers), lettered in basketball at Dartmouth, graduated Phi Beta Kappa, and worked his way through Harvard Law School playing professionally for the Boston Celtics and St. Louis Bombers. He spent the war years with the Navy, and as a Rhodes scholar earned a B.A. and M.A. from Oxford. He later served as a justice of the U.S. Court of Restitution Appeals in Nuremburg. "Air Mail" Morton quarter- backed the Dartmouth football team (where he earned his nickname), captained the hockey team, received all-America honors in both sports, and was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1971. He began calling plays on Wall Street in 1932 as president of his own investment firm, and retired in 1974 as president and director of the American Express Company. Morton was elected a trustee in 1972.

A trustee since 1976, Walter Burke '44 left Dartmouth in 1942 to join the Navy as a lieutenant. He has an LL.B. from Columbia and is noted for his financial acumen. He has been chairman of Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation and Fairchild Industries Inc., and associated with the Fairchild Foundation. Another money expert and a Tuck graduate, Richard Lombard '53, lists his occupation as "private investor." The investment firm he started with classmates William Vitalis and Paul Paganucci (who is now a Dartmouth vice president) was notably successful. Lombard is president of the Kettering Family Foundation, vice-chairman of the Sloan- Kettering Institute, and became a Dartmouth trustee in 1971.

David Smith '35 joined the Dartmouth board the same year as Lombard. President of the San Francisco investment firm of Scudder, Stevens & Clark, Smith also has a reputation as a financial expert. He earned his M.B.A. from Stanford and became the first president of its business school alumni association. Besides serving on the Dartmouth board, he also has been a trustee of Mills College and the Pacific School of Religion. He's an expert fly fisherman and loves music — particularly playing the autoharp.

Although six of the trustees have law degrees, Berl Bernhard '51, Robert Kilmarx '50, and Donald McKinlay '37 are the only three in active practice. The three of them also were members of Casque and Gauntlet and Palaeopitus. Bernhard came on the board in 1974 and is the College's main contact with Washington politics. In 1961, President Kennedy appointed him staff director of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, and he has been active in Democratic Party national affairs, serving as counsel to the Democratic National Committee and as national campaign manager for Edmund Muskie's presidential bid in 1972. At Dartmouth, he was president of the Undergraduate Council and a Phi Beta Kappa graduate.

Kilmarx has a law practice in Rhode Island and has been a trustee of the Rhode Island School of Design and of the Hurricane Island Outward Bound School, as well as a director of the United Way, Planned Parenthood, and the United Arts Fund. For Dartmouth he has been chairman of the Native American Visiting Committee and, before joining the board in 1972, was chairman of the Alumni Council's committee to study the use of the Indian symbol. McKinlay is a trial lawyer from Denver who once served as Colorado assistant attorney general. He chaired the state's commission on higher education and has served on boards of the Urban League and the United Negro College Fund. Another Barrett Cup winner, McKinlay played varsity basketball.

Norman McCulloch '50 is chairman of the Campaign for Dartmouth. He also has been national chairman of the Alumni Fund and a president of the Alumni Council. He is owner, president, and treasurer of Microfibres Inc., a Rhode Island manufacturing firm, and became a trustee in 1975. In addition to several Rhode Island business directorships, he has been a trustee and former president of St. Andrews School, a member of Barrington College Associates, and a corporator of Roger Williams College.

Richard Hill '41 and Ralph Lazarus '35 are the two trustees longest involved in big business. Hill, elected in 1974, is chairman of the board of First National Boston Corporation and the First National Bank of Boston. Lazarus, known to his employees as "Mr. Ralph," is chairman and chief executive of Federated Department Stores Inc., the largest U.S. department store chain. Lazarus has the most seniority on the board, serving since 1968. Other trustees respect his ability to "find the fat in a budget," and he has a reputation for getting things done. Lazarus has a host of honorary degrees and a long record of service to business, government, education , and the arts. Hill has been involved in metropolitan Boston and regional civic affairs, particularly transportation. He is an accomplished yachtsman and has been described as "a perfectionist tempered by good judgment and understanding."

When Dartmouth trustees are asked if there is diversity on the board, many of them point to R. Harcourt Dodds '58, a black, who joined in 1973, or they mention David Weber '65, whose election in 1971 was heralded as bringing to the board a much-needed youthful point of view. As of this fall, they also talk about Priscilla Frechette. Dodds, a member of Casque and Gauntlet and Palaeopitus, graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Dartmouth and earned his law degree from Yale. His path to the Ford Foundation was via a two-year stint as an assistant commissioner for native courts in the Ministry of Justice in Northern Nigeria and a series of top city and state legal positions in New York. A newspaper columnist once described Dodds as someone who "does not bristle."

Weber, an English teacher and coach at Phillips Exeter Academy, has a reputation for being thoughtful and perceptive. "When Dave talks," one trustee said of him, "we all listen." Weber was a varsity cross-country runner in college, president of the Undergraduate Council and of Phi Tau fraternity, and as a graduating senior won both the Barrett Cup and the Smith award for his contributions to the College. He recently edited a book, CivilDisobedience in America.

Priscilla Frechette, the first woman to serve on the Dartmouth board, was able to take her seat this September because William Morton volunteered to retire several months early. She graduated from Smith in 1942 with a mathematics major, and this past June obtained a master's degree in business from the University of Massachusetts. She has been active in business and educational affairs in New Hampshire, chairing the Keene School Board and the Kingsbury Machine Tool Corporation, and serving on the board of the New Hampshire Public Service Company. She is the widow of Henry H. Frechette '41 and the mother of David '67, Edward '82, and Peter '82.

DARTMOUTH has a total of 16 trustees, including two, President Kemeny and New Hampshire Governor Hugh Gallen, who hold their seats by virtue of their offices. It is the 14 regular trustees, however, who hire and fire the president and make policy for the College. By all indications, they take their responsibilities seriously. Some spend more time attending to the College than to their own businesses. When asked about the nature of their role, they tended to describe their obligations in a combination of financial, educational, and even emotional terms. "We're custodians of the future, guardians of the present, and repositories of the past. These are cliches, but they're true," McCulloch said in an interview this summer. Munroe said the board's responsibility toward the College was to maintain the same excellence Dartmouth has enjoyed in the past, and Weber said it was to maintain the College's financial health without damaging its institutional integrity, goals he thought to be sometimes in tension.

Lombard divided the day-to-day responsibilities of a trustee into two parts. The first is a trustee's official function as a member of the board who works on various committees, attends meetings, and votes. The second function is to be a resource person, "an individual who is available to help where he can." Lombard explained that the way time is divided between the two roles varies from individual to individual, depending on the amount of time available, proximity to Hanover, and specific interests. Two trustees, McCulloch and Smith, have been virtually full-time fund- raisers during the Campaign for Dartmouth. Others are involved in Dartmouth-related — boards and committees not directly associated with the undergraduate college boards of the Hanover Inn, Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center, and affiliated graduate schools, for example — and still others have concerned themselves with different areas of student life — with athletics, fraternities, the arts, and minority affairs.

Ostensibly, the trustees set policy for the College and the administration implements it, a division of responsibility that sounds easy but is said to be difficult in practice. According to Bernhard, one of the biggest problems facing the board is "trying not to be confounded by the murky area that exists between the two. Sorting this out is an endless process. You have to keep your nose in the operation so you can keep your fingers out of it." McKinlay said that "we try to stay out of management, but when matters are brought to the board they have to be dealt with." The reason that the board might be involved in more issues than it ought to be, McCulloch explained, is not that the administration is failing to do its work, but that there recently have been more problems to be handled than ever before, and because the board has become involved to a greater depth in some issues. "That might not be desirable forever, although it has been both desirable and necessary in the seventies" McCulloch added. "We've had to jump in — willingly — in areas where former boards never had to, but in the future the division of responsibility might be redefined in subtle ways. The board might revert to being more of a policy-making and less of a legislative body."

The president has the ambiguous role of being both a trustee and the College's chief executive. McLaughlin said the relationship between the board and Kemeny is comfortable but also semi- formal— not taken for granted by either side. Burke described a "healthy tension and a straightforward expression of opinion" between an active, well- functioning board and a capable chief executive, as well as a mutual respect and willingness to listen. If there is a question about the division of responsibility, Burke added, it is discussed and worked out.

Part of the president's responsibility is to bring matters to the board's attention, make a clear recommendation, list alternatives, and implement the eventual decision. The trustees say he does this efficiently and diplomatically. Although his recommendations carry considerable weight, they are not enacted automatically. Weber observed that serious divisions between the board and Kemeny are usually avoided because the president is careful not to get locked into an adversary position and because he heads off potential confrontations before they happen. Dodds said that if serious disagreements happened too often "we wouldn't have the president," and that the recommendations Kemeny advances are often for the purpose of achieving a resolution or solidifying a position, and not necessarily a reflection of a strongly held position of his own.

Kemeny's executive assistant, Alexander Fanelli '42, who acts as the liaison between the board and the College, has the responsibility of keeping the trustees informed. He forwards mail, position papers, reports, news clippings, and a thick agenda book prepared in advance of each meeting. (Bernhard remarked that he is "surfeited" with preparatory information before board meetings, and has "clearly enough material for three or four hours of reading one night per week.") The trustees, in general, seem pleased with the quality of administrative support they receive from college officers, and when asked if the official channels of communication cut them off from points of view opposed to those of the administration, they insist that they are kept — and keep themselves — adequately informed of a variety of perspectives.

Getting enough information doesn't appear to be as much a problem for the board as finding out how widely different opinions are held. Because of the "tendency of activists to press their views forcefully," Munroe said, the board sometimes gets an unbalanced impression. Lombard agreed: "The loudest groups don't necessarily express the feelings of the majority." Several trustees voiced their suspicion of the informational value of "discussions" — particularly with student groups — that have turned out to be "preplanned confrontations."

The quarterly board meetings are held in November, February, April, and June (there is also an unofficial summer retreat), and at each two- or three-day trustee weekend, meetings of some of the ten or so committees and subcommittees are scheduled. Although meetings of the whole board are the occasion for final deliberation and voting, they are not the major time-consumers or where the bulk of the work is done. The real work of the board, the trustees emphasized, is conducted through the committees. They do the legwork to minimize the amount of time the board has to spend in consideration and debate of issues. They receive information, research issues, work up recommendations, and provide a forum for interested parties to express opinions. Although the usual model is for a college to have a large, primarily honorary board with a small executive committee to do the work, the system here requires each member's active participation. Committee assignments are made by the chairman in accordance with a trustee's personal interests, ability, and an informal schedule of rotation.

It used to be that the executive committee handled almost anything that came up in the interval between meetings of the whole board. It still has that power, but in 1974 the board directed it to focus on repetitive, routine matters such as appointments, receiving recurrent reports, and handling real estate transactions of less than $500,000. If there is something that requires immediate action, a meeting of the executive committee can be convened at one of the monthly Boston or New York meetings of the investment committee (the two have almost identical memberships), or a vote can be taken over the telephone. This rarely happens, however, because the board prefers to operate, according to Fanelli, in a "non-panic, orderly manner."

The chairman, elected annually, has the responsibility for keeping the board's operations running smoothly. He works directly with the president and the administration to establish the agenda and to make sure meetings function around it without getting derailed on side issues. "Extraordinarily good at being a chairman" is how one of the trustees described McLaughlin. Others complimented his ability to allow - full discussion without allowing business to lag. Besides presiding at meetings, the chairman also is the official conduit between the board and the administration. Any trustee concerns are expressed through him and he coordinates any necessary action. Although he and Kemeny have a scheduled phone conversation every two weeks, McLaughlin said he is careful not to get involved in the day-to- day operations of the College.

Because of McLaughlin's leadership, the small size of the board, and the quality of preparation by each member, meetings are said to run efficiently. Weber observed that the agenda is too tightly structured to allow much latitude in how business is conducted, although he noticed a "nice play between efficiency and a sense of informality. Jokes are permitted." Bernhard said he hasn't found meetings to be particularly rushed, although he has felt pressure to make sure the agenda is covered. Lombard appreciated the discipline" imposed by the chairman, and Dodds characterized the meetings as "purposeful." He joked that it "sometimes feels like we're producing a battleship." Hill described the atmosphere as "collegial — a meeting of good friends who may disagree but who have a great amount of respect for each other," and Burke said that at meetings, particularly executive sessions, "there are absolutely no sacred cows as to people or subjects." There has, however, been a change in the atmosphere of meetings over the seven years he has worked with the board, Fanelli observed. Earlier meetings were simpler, had less crowded agendas, and, as a result, were more relaxed. "Not that there wasn't anything to do," he added, "but there was more time to do it." He said that the College now seems more complex, partly because of an increase in the amount of government regulation and requirements.

THE trustees differed in their estimation of whether or not running Dartmouth has become a bigger job for them. Morton declared that running a college "does not seem to be getting more complicated, time-consuming, or involved. It always has been time-consuming." Smith said it used to be, long before his tenure, that "the trustees met for two hours and that was it. Now we're taking two and a half days." Lombard described the increase in complexity as "close to the end of the comfort line," while Kilmarx claimed that increasing pressures have had a constructive effect, moving the board to "tighter and more efficient operation, schedules, and agenda." Bernhard, the Washington lawyer, talked about the "inevitability of bureaucratic inroads on the capability of the College to regulate itself," and cited increasing federal involvement in a college's affairs as "the kind of thing that does not make a trustee's job any easier."

McCulloch said he had no doubt running a college has recently become a much more involved task, but he added that blaming new government regulations is "the easy answer." While acknowledging that the board has to spend more time now reviewing federally mandated social programs — affirmative action, for example — McCulloch argued that one of the main reasons for the increasing burden on the board has been its increasing interest in monitoring and improving different areas of college life. That interest started in 1968 with the McLane Report on the situation of minority groups here, McCulloch said, and has come to include fraternities, the admissions process, communications and public relations, and athletics. McCulloch said that the decision to take a serious look at these and other areas was "time- consuming but rewarding," and also practical because most of them impinge on the budget and financial health of the college. Ralph Lazarus was one of several trustees to point to a whole pattern of increasing complexity in both business and educational institutions. "The things that have made business and universities much more complex in the past decade," he noted, "are the social changes that have taken place, the increase in government regulations, and the intensity of feeling and view- points on the part of all constituencies."

If the pattern continues to repeat itself, how will a small board of volunteers continue to handle the work? Some trustees suggested that the period of greatest physical growth at the College is over and hoped that the demands on the board would soon reach a plateau. The most commonly proposed solution, however, was for the board to reorder its priorities every so often, delegating more authority to the administration (or stepping back from properly administrative functions it has assumed), and making more effective use of committees, giving the executive committee a broader charge and allowing other committees to make decisions that would be ratified by the board. No one thought that having more trustees would necessarily allow the board to work more efficiently. The board's small size, many trustees argued, is one of its assets and prime attractions. Although they claim to discuss frequently the possibility of making the board larger, one trustee, who asked not to be quoted directly, said that the last time the size of the board was increased, the quality of its deliberations diminished appreciably.

FOR many of the trustees, a commitment of time is one of the greatest demands made of them by the College. George Munroe admitted that "the substantial demands on my time are more than I had anticipated," and suggested there is a basic conflict between the importance of having people on the board who can give the necessary time, and the desirability of also having "busy people who are involved in other areas of our society in leadership positions." Morton insisted that trustee responsibilities have to be a top priority for anyone who accepts the job. It is made quite clear to prospective trustees, he said, that they would be expected to prepare for and attend the five board meetings and, depending on their assignments, six to 12 committee meetings. Morton, who came on the board shortly before he retired from American Express, said he is glad he was not asked to serve several years earlier because it would have been difficult to do justice to Dartmouth without encroaching on his business responsibilities.

Many trustees said they give more of their time to Dartmouth than to any other commitment outside of their occupations and families, partly because of the issues that have to be dealt with, according to Lazarus, and partly because of the "deep personal interest the trustees have in Dartmouth and its development." Kilmarx attended 22 different board and committee meetings one year, and Burke estimated that being a trustee takes five to ten per cent of his time. The demand varies, of course. It's heaviest just prior to regular board sessions and important committee meetings. Dodds said he has difficulty determining where his work for the Ford Foundation ends and his work for Dartmouth begins because their interests often overlap. Weber noted that he counts on spending a full day's work in preparation for each trustee meeting. Hill confessed he finds it difficult to find the time. "I was getting along very nicely with my other boards until Dartmouth came along," he said. "Dartmouth has a way of absorbing a great deal more of your time than you expect it to."

There are historical accounts of controversy between Dartmouth boards, presidents, and alumni, but there is no contention that today's trustees lack dedication to the College — although it is sometimes charged that the group is too homogeneous. When it was proposed to Fanelli that there might not be enough diversity on the board, he replied, "Not enough diversity for what?" He argued that the trustees are charged to maintain Dartmouth as a high-quality educational institution, and that in recent years that responsibility has demanded sound management and financial skill. "Dartmouth is fortunate to have as much financial experience as it does on the board," he claimed, adding that although diversity would be welcomed, it would be a mistake to cut back on the board's present talents. That sentiment seems to be shared by both College officers and trustees. Burke maintained that the board and its committees function well with their present membership, that there is a "delicate balance" and a "family relationship" with "healthy tensions." "Although it may not be all that obvious from the outside," he continued, "there is a goodly amount of diversity within the board." Weber frankly admitted that "the present composition of the board isn't as diverse as it should be," but he recognized the difficulty of representing a wide variety of backgrounds in such a small group. Michael McGean '49, secretary of the College, cited the difficulty of filling the board's "needs" as well as achieving diversity in age, sex, race, and geography. "In the end," he concluded, "the challenge is to find 14 people, plus two ex-officio members, who will stand for the best interests of the College."

Another hedge the trustees have against criticism that their club is too exclusive is their claim that none of them represents any specific part of Dartmouth, and that they all are looking after the best interests of the College community as a whole. "The fastest way for a trustee to lose credibility on the board," Weber said, "is to advocate any particular constituency." "The balance between representing a point of view and a constituency is more a matter of emphasis than a finite line," Dodds observed. "You bring the total of who you are to decisions. That perspective is what is important. It is proper, timely, and important to raise questions from that point of view. Having been a black student on scholarship, I bring to our discussions a certain point of reference, amplified, of course, by the passage of time. It's possible to voice those concerns, which may indeed be similar to those being raised by specific groups, without those concerns being a product of a particular petition or protest meeting."

The trustees maintained that while no particular group has an advocate on the board, the board takes pains to hear differing points of view before making decisions. They expressed their pleasure over what they saw as improved relationships and communications with alumni, specifically with the Alumni Council, but at the same time denied that concern for alumni reaction has been an overriding element in their deliberations. While some lamented the lack of much social interaction between the board and the faculty, both trustees and professors seemed to agree that faculty representation at trustee committee meetings was at least communicating the faculty's concerns. (One young professor disagreed strongly, charging that interaction between the faculty and trustees is carefully regulated to represent the status quo and to eliminate criticism.) The same claims for the value of representation in committees was made in the case of students. A number of students who have participated in recent trustee committee meetings indicated that members seemed genuinely interested in the students' perception of issues and interested in their comments, although one student complained that "definite and specific channels" had to be negotiated in order to make arrangements to meet with the board, and that sometimes student opinion is solicited too late in the course of deliberations. Two or three of the trustees do have informal breakfast discussions with students during each trustee weekend — all a student has to do is sign up at Fanelli's office — and the trustees have cooperated with student groups in holding open hearings, most recently over the issue of the male-female ratio.

On the whole, the trustees denied being out of touch with the Dartmouth family. They pointed to their reading of student publications, their attention to votes taken at faculty meetings, their meetings with alumni officers, and their involvement in class affairs. In- addition, they claimed to cultivate and maintain contacts with individuals who have a variety of interests in the College. McGean said he thinks "the board is the first to realize that if it can't bring the important constituencies of the College together in terms of policy, it can't be a very effective board. One of the things that makes this board work is its extraor- dinary concern for the legitimate interests the various groups have."

With the exceptions of the newest trustee, Sally Frechette, widow of an alumnus, and President Kemeny, adopted by the class of '22, and Governor Gallen, whose presence on the board is mandated by the College's charter, the trustees all are alumni, a situation that might seem parochial, but one that is defended on grounds that only alumni are likely to be concerned enough about Dartmouth to make the commitment that service on the board requires. There is no rule that says non-alumni can't be appointed, but when pressed, the present trustees affirm that matriculation at Dartmouth is an important, though not essential, qualification for membership in their ranks. Other reasons given for preserving the tradition are that a large part of a trustee's job is alumni relations, and that the board naturally is interested in candidates who care for the College and have a record of serving it. Because what the board is trying to preserve and make prosper, in Kilmarx's words, "is the best of the pattern of Dartmouth College, it helps to know what that pattern has been." Kilmarx went on to say, however, that having had an undergraduate experience at Dartmouth is an advantage in a trustee only as long as having mostly alumni on the board doesn't limit quality.

Although the trustees repeatedly mentioned the importance of having financial and legal experience represented on the board, the most important qualification for membership was described as good judgment or "horse sense." "The board needs able generalists, Weber said, and added energy, commitment, an open mind, and the ability to view one's own position with detachment to the list of desirable attributes. "There's a good bit of truth in the old cliche that you want trustees who can give wisdom, work, and wealth," Weber observed. "You at least need two out of three."

When the board finally decided to act on the desirability of having a female trustee, it was in somewhat of a dilemma. The long-standing tradition had been to appoint alumni, but there were few women in that category, and those that there were had only recently left college. Most of the women had not yet had a chance to broaden their experience or to prove their abilities beyond Dartmouth, and those who were potentially qualified to serve on the board were likely to be putting all their energy into new careers. As a solution, the trustees took good advantage of the "Dartmouth family" concept and found a female candidate with both strong ties to Dartmouth and proven ability Priscilla Frechette then accepted Morton's offer of early retirement.

Frechette was appointed as one of the board's seven charter trustees, who are nominated and elected by the board itself and eligible to serve three five-year terms. The other seven are alumni trustees, nominated by the Alumni Council and then routinely elected by the board. Alumni trustees are only eligible to serve two terms, but in all other respects their duties and powers are the same. If the Alumni Council's choice of a trustee is challenged, as it was for the first time in 1977 when the regular nomination of George Munroe was opposed by the petitioned nomination of the Reverend Pauli Murray, the College's alumni are balloted. Munroe was elected by a wide margin, and the alumni constitution was subsequently amended to specify that future nominees for alumni trustees must have matriculated at Dartmouth or one of the associated schools (Murray has an honorary degree), and to raise from 100 to 250 the number of signatures necessary for a petitioned nomination.

MANY colleges and universities regularly hold popular elections to choose trustees. The obvious advantages of such a system are that it involves more alumni in the process, seems more democratic, and presents more choices from a wider variety of candidates. One disadvantage, according to Fanelli, is that a popular election "isn't a particularly effective way of getting a better board than we now have." He said that the board and the Alumni Council's nominating committee know the board's needs better than the average alumnus, and that it would require "tremendous expense and effort to educate alumni to make intelligent choices." McGean cited the additional disadvantage that in a popular election there is usually a proportionally small return on the ballots — 15 to 25 per cent at the schools that use the system — and that some of the best candidates might decline to participate in a political contest that pits them against each other.

"I think there is also the philosophical question of what really is the best way, especially on a small board, to get down to very best final candidates," McGean added. "You can get a group to study and go after the best people, meet with the trustees and president to find out what sort of person is needed, talk to students, get involved with the College, and do a lot of work. Is that a better way to come up with the kind of person who will best serve Dartmouth, or is it better to simply suggest to alumni that there are a lot of people who can do this job and throw it open? You can argue either way, but history suggests we have obtained very able people to serve on the board and that the present system has been working."

Although it reportedly takes some arm- twisting to get some prospective trustees to accept an appointment — usually their reluctance is due to the time required — most nominees are, in the words of some of the present trustees, "honored," "flattered," "challenged," and "delighted" to be chosen. No one interviewed could think of any recent nominee declining the appointment. Their reasons for accepting are what one might expect: They have an interest in education, and most have a long record of involvement with and service to the College and their classes. They say they work for Dartmouth out of a sense of responsibility, dedication, and affection. The system of alumni service here has its own built-in gratifications, although most of the returns on service, except for oc- casional plaques, mementos, and citations, are intangible. There is recognition, but there also are, in Burke's words, "real and substantial rewards of the mind and spirit." Kilmarx said he accepted because he feels strongly about the College and valued the opportunity to serve in an important capacity.

The trustees are not a group of X good old boys who want to go along with everything that comes up," McKinlay replied when asked about how the board decides on issues. Although various trustees differed in their assessment of how important to the board consensus is and how often it is reached, they were unanimous in affirming the unpredictability of votes, particularly which way certain individuals would vote. Bernhard claimed that although votes sometimes are divided, unanimity is desired: "On the really vital issues we have moved heaven and earth to see if accommodation can be reached to resolve the legitimate disagreements of a minority." McLaughlin said that as chairman he never has felt the board needed to have total agreement on any issue. Weber's evaluation was that the board's concern for consensus depends on the importance of the issue and on whether or not there has been enough debate. If everyone has had a chance to speak, the board votes and moves on. Votes, according to Kilmarx, are invariably written and formal — it isn't a "sense-of-the-meeting" system. "It's important for trustees to be accountable," he claimed, "and for votes to be documented. "When there is disagreement, it reportedly is accommodated and respected.

"We don't proceed by caucus," McKinlay pointed out, "and to my knowledge there's never been a group that goes off to the side and says 'let's try to ram this through — here's the strategy.' " McCulloch said that "fierce independence" on the board goes hand-in-hand with a sincere desire to do what is best for the College. During debates, members with strongly held opinions are willing to be persuaded to another point of view, it was reported, and when it comes time to vote there are no readily identifiable 'conservatives' or 'liberals,' except possibly when it comes to investment decisions. On important issues, when trustee unanimity is perceived to be an important signal to the college community, members with doubts about a particular decision are said sometimes to go along with the majority in order to allow the board to speak with a single voice. Or if there is a split vote, a gentlemen's agreement and sense of duty to the institution prevents dissenters from filing a minority opinion. When there is a policy given to the president to carry out, Bernhard explained, the president "is entitled to the support of the policy he is expected to implement."

Financial stability and the preservation of quality were the dominant responses when the trustees were asked about their priorities for the College and for the operation of the board, but other concerns were also raised. McLaughlin said he wanted to assure adequate resources in all areas — students and faculty as well as money — and that he didn't want the workload to become so great for trustees that they would become frustrated in their ability to discharge their responsibilities. Lazarus wanted to make sure the board continued to "move toward a better sorting out of priorities for discussion." Hill saw a need to identify and encourage student leadership, and Kilmarx said that where the College faces one of its greatest challenges is in the area of student life. Bernhard would like the board to take a close look at year-round education, relationships between men and women on campus, and the quality of life at Dartmouth for minority students.

Lombard set a high priority on getting the College to live within its income, and McCulloch said that as the board wrestled with finances he didn't want it to forget that "students are our most important product." Weber said he was worried about the disparity between educational costs and family income, wanted the board to be mindful of the process by which it is informed and makes decisions, and hoped for student initiatives toward a more congenial social climate for women and minorities at Dartmouth — "without getting into an increasingly more visible administration."

Morton replied that in the student admissions process more emphasis should be put on personal qualities and potential for becoming "good citizens," and less on intellectual accomplishment. Dodds hoped for expanded communications between the board and faculty, more time for the board to address broad issues, and a better feel for the impact of government policy on the College. He also wanted to make sure the College fulfills its obligations to women and minorities, and to encourage the atmosphere of a residential learning community. Frechette would like to learn more about what women feel is both good and bad about their experience at Dartmouth, and to make sure that women who choose to attend Dartmouth have the correct reasons for doing so. She added that she also was concerned about recent controversy. "There should always be dissent and people speaking their minds," she said, "but not to the point where it tears the College apart. I hope that Dartmouth never loses that special something it always has had."

Although the trustees seem to be generally satisfied with their image with alumni, students, and the faculty, a few of them do perceive some "misunderstandings." Munroe suggested that "people might loose sight of the fact that we are all trying to do the best we can for the College. ... We're all volunteers. Nobody's getting anything out of it." Lombard said he sees a "common misperception that the board is not responsible to anybody. But the board does listen — intently." Smith thought that the College's "financial problems and number of administrators are often misunderstood," and that "most people don't appreciate the complexity of running an institution of this size." McKinlay hoped that "most alumni would understand that we do our homework and go out of our way to get opinions and facts."

There are people who might believe we are mysterious and arbitrary, making decisions in a vacuum," Hill said. "I don't think that's the case." Weber defended the board as "more independent than some alumni think." Kilmarx remarked that he sometimes has the impression that despite the trustees' efforts "to represent the entire Dartmouth family, we're sometimes perceived as representing just one element of that family." He added that some people might have the "impression that the board and College exist for many reasons other than the real one — to educate students and meet their needs."

People who see more contrasts than similarities between the College today and the one they attended, and those who deplore the changes of the past decade, might well criticize the board for being too willing to tinker with the established patterns, while those who favored those changes have sometimes found the board reluctant and slow to implement them. The trustees, of course, see themselves in the middle, wanting to preserve tradition, and perhaps tending toward caution in financial affairs, but responsive to the future and open to change as it is needed. "It is inaccurate to say we are either conservative or liberal. We are realistic," Kilmarx claimed.

The trustees expressed some — but not many — self-criticisms. Morton charged that "we've been overly concerned, both collectively and individually, about the special problems of minority groups, women, students, faculty, and the alumni. You have to look at the whole picture, without worrying about a popularity contest." Another trustee, who declined to be quoted directly, said the board might be suffering from a lack of public inquiry, that there should perhaps be more openness, and that the mystique surrounding it might be loosened a bit.

Most criticism of the board seems to stem from dissatisfaction with particular decisions. While the wisdom of the decisions can be disputed, and while suggestions might be made for improvements in the board's organization and procedures, no indication could be found that the trustees are anything but able, hard-working, and dedicated. It seems that any real criticism of the present Dartmouth board has to come out of some basic criticism of the College, of what it teaches students, of the alumni it produces, and the values they hold. The purpose of the College has been affirmed by the trustees to be "the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society." Unless there is an argument with that mission, or a perception of its neglect, and unless the people chosen to lead Dartmouth represent less than the best, there isn't much room for fundamental complaint.

"Sometimes people who carry this much responsibility are seen in an adversary relationship," McGean observed. "It's when you get to know them as very human, as wanting the College to be the institution we all want it to be, and as working very hard at it, you realize the College is really in awfully good hands and that we're lucky to have the people we do. You feel comfortable in letting them have all the power they have. The final decision-making around here has a pretty good track record. We don't look back on too many major decisions and say what disasters they were."

McLaughlin (top) is chairman of Toro.Weber teaches prep school English.

McLaughlin (top) is chairman of Toro.Weber teaches prep school English.

Morton (top), McKinlay (middle), andMunroe were star athletes in college.

Burke (top) and Lombard bring financialskill to the Dartmouth board.

Burke (top) and Lombard bring financialskill to the Dartmouth board.

Hill (top) runs a bank, and Lazarusruns Federated Department Stores.

Hill (top) runs a bank, and Lazarusruns Federated Department Stores.

McCulloch (top) and Smith are workingalmost full-time now as fund-raisers.

McCulloch (top) and Smith are workingalmost full-time now as fund-raisers.

Bernhard (top) is a Washington lawyer.Kilmarx practices in Rhode Island.

Bernhard (top) is a Washington lawyer.Kilmarx practices in Rhode Island.

Frechette (top) and Dodds: Two exceptionsto the pattern of white males.

Frechette (top) and Dodds: Two exceptionsto the pattern of white males.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

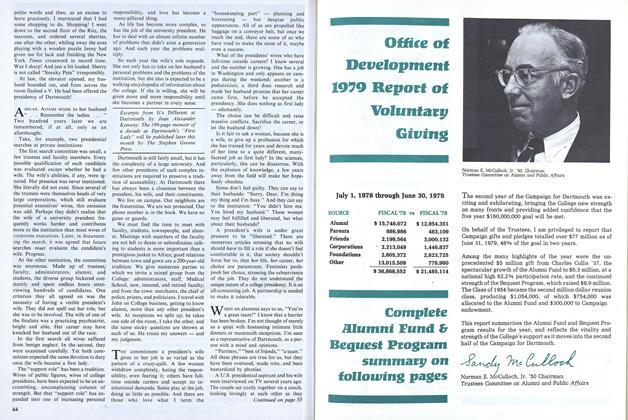

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleNumismatist

October 1979 By M.B.R.

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

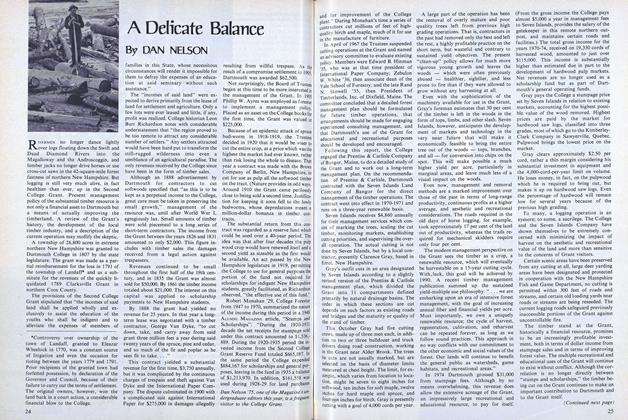

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureDrinking

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureConjuring Ethics in the Curriculum at Dartmouth

March 1981 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS -

Feature

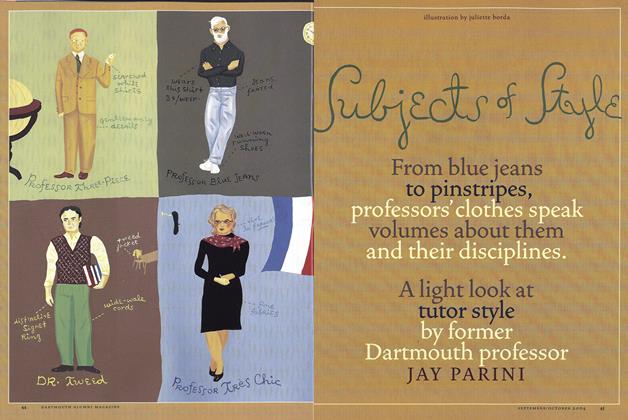

FeatureSubjects of Style

Sept/Oct 2004 By JAY PARINI -

Feature

FeatureWomen on the Verge

Mar/Apr 2003 By Jennifer Kay ’01 -

Feature

FeatureCreating Creators

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

FeatureCAN CONGRESS SURVIVE?

JANUARY 1965 By ROGER H. DAVIDSON -

Feature

FeatureKeeping Dartmouth Diverse

JUNE 1983 By Steve Farnsworth '83