Energy seems to be on everyone's mind lately: in Washington, in Hanover, and this past summer, in Aspen. Bruce Judson '80 spent the summer working for the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies as an energy program consultant. He cashed in on what could be the institute's last summer in Aspen, for the renowned think tank just announced plans to move to Baca Grande Ranch north of Alamosa, Colorado. Other offices are in New York, Washington, D.C., Hawaii, Berlin, and Japan.

The institute, a non-profit organization, seeks possible alternative approaches, not simple answers, to solving problems. "Human beings are concern of the Institute," reads its statement of purpose, "and highly qualified people are its resource."

Judson got a chance to meet these people, leaders from government, industry, and academia. On his first night in Aspen, his boss invited him for dinner. "We were joined by John Gardner," said Judson. Gardner, one time secretary of HEW, later founded Common Cause, a lobby in Washington. "That kind of experience characterized my summer in Aspen," Judson related. Yet, it was not all meetings and dinners. Judson also represented the institute on the tennis court, sometimes facing opponents from Washington. He still wonders, "Do you beat a congressman?"

The mid-July conference on which Judson concentrated examined centralized versus decentralized energy technology. John Sawhill, energy czar under two Republican administrations, chaired the Aspen Energy Commission; Judson wrote up the conference report.

How did Judson achieve the distinction of working in an environment where he was the only one under 30? A Policy Studies major, Judson served as acting president of the class of 1980 for six months and worked for two years as one of two student representatives on the College Council of Budgets and Priorities. During the summer of 1978, he worked for the New York Council on Economic Priorities. His introduction to the national political structure came last fall and winter when he worked as a staff assistant to the House Subcommittee on Energy and Power. There he wrote a report on energy and helium.

"The high point was the hearings. For me that was the most fun," recalled Judson. He helped to write HR2620, a bill which requires conservation of helium by private industry in government structures. "It was a learning experience to sit down with the lawyers and legislative council to design a bill," said Judson. HR2620 went to the House for consideration this session.

In Washington and in Aspen Judson saw many of the same people involved in energy, but in Aspen he was on a par: "I traded ideas very much as an equal with the people I ran into," he said. "That is what made it such a rare experience."

What are some of the energy issues they worked on? First, defining the problem. "We are in this dilemma because of institutional inflexibility based on old themes of cheap energy," explained Judson, emphasizing pricing, lack of incentives, lack of public knowledge, regulations, and capital shortages as examples. "We should be looking for greater flexibility, greater diversity of approaches. The current system does not allow for that."

The Aspen Energy Commission looked into conservation technologies which increase efficiency in energy use. "There are conservation technologies where people will not debate you," asserted Judson. One such example is insulation of homes.

Judson returned to Hanover this fall, leaving the glory and sun of Aspen behind. His only disappointment about the summer, he said, is "that Henry Kissinger did not show." Judson will be working on his thesis for the Policy Studies Program, focusing on energy and social change.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

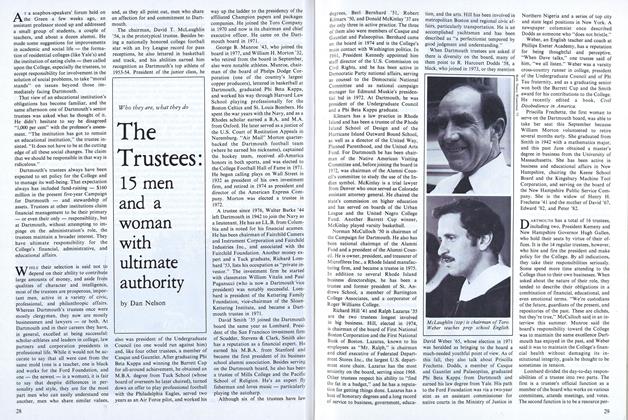

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTwo at the Top: On being a woman, a wife, a partner

October 1979 By Jean Alexander Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureSummer Rep

October 1979 By Nancy Wasserman -

Article

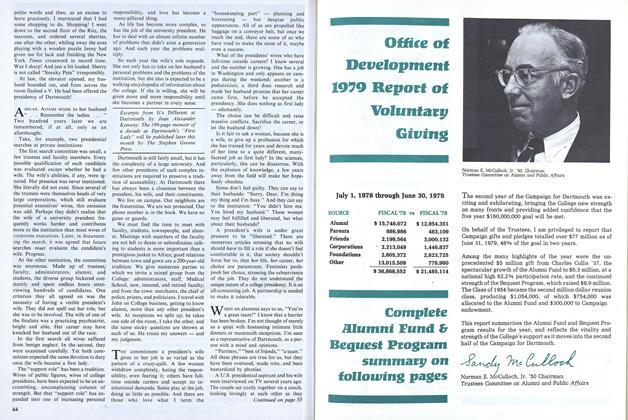

ArticleOffice of Development 1979 Report of Voluntary Giving

October 1979 -

Article

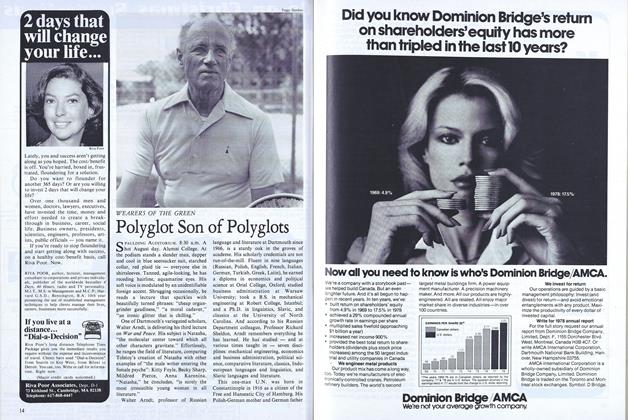

ArticlePolyglot Son of Polyglots

October 1979 By NARDI REEDER CAMPION -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1979 By JEFF IMMELT