Talks with a freshman senator

IN May of 1978, Paul E. Tsongas '62 announced his candidacy for the Senate seat held by Massachusetts Republican Edward Brooke. With polls showing his statewide recognition at a scant 12 per cent, Tsongas was considered a long shot at best. But on November 7, at the close of a skillfully managed campaign that had weathered a tight contest in the September Democratic primary, the two-term congressman bested Brooke by a ten per cent margin.

Tsongas' job in the election had been to prove to the voters that he could do for the state what he had done for the fifth congressional district — an area to the west of Boston that encompasses both affluent suburbs and economically blighted mill cities. Only a short time after having been sworn into the Senate, he was attempting to deliver on that promise. Last March, on a blustery Saturday, I had the opportunity to travel with Tsongas, observe him in action with his constituents, and sample some of his off-the-cuff views and prognostications on a number of personalities, events, and issues. Later, at the end of the summer, I followed up on some of the issues that Tsongas had raised on that spring day.

ONLY minutes after stepping from his early morning St. Patrick's Day flight from Washington, Tsongas had replaced his conventional tie with a bright green one. We were to be visiting several cities north of Boston, in two of which "town meetings" had been scheduled. These meetings are a practice expanded from his congressional days, enabling citizens from all over the state to have him address their concerns and answer their questions directly.

Driving to our first destination, Tsongas, with typical directness, commented on the reaction in Washington to his replacing the only black in the U.S. Senate: "There really has not been as much reaction as I had anticipated. I don't think there's any question that Ed Brooke is fondly remembered both by his colleagues and by people who were concerned

with issues such as housing and women's rights. It's not that Ed Brooke was defeated by someone who has totally different views, but I think in terms of the areas that I am involved in — specifically Africa, energy, and the cities. There is a need for someone who holds my views and, in the sense that I am effective in promoting them, then Ed Brooke's shoes can be filled. There was never any attempt or desire to be involved in the same issues he was involved in only for the sake of replacing him. If that was all I had wanted to do, there would have been no point in running."

The three concerns Tsongas mentioned had been emphasized during his campaign for the Senate and had received the major focus of his attention during his two terms in the House.

Tsongas' view of Africa is backed by unusual credentials. After graduating from Dartmouth, he spent two years with the Peace Corps in Ethiopia before attending Yale Law School. Because of his African service, Tsongas believes himself to be the only person in the Senate who has actually lived as an ordinary individual in a Third World country, and it is no secret in Washington that Tsongas hopes eventually to find a seat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee's sub-committee on Africa.

In his second address on the Senate floor, Tsongas took issue with the Administration's failure to recognize Angola. Citing the narrow vision with which the super powers view the Third World, Tsongas exclaimed: "In the Cold Warrior's conception of the globe, the only struggle is between East and West ... Africans matter only to the extent to which they can be identified as pro-West or pro-Soviet."

BUT for the Massachusetts Democrat visiting his home state, the questions on the minds of the people were closer to home, with energy and the economy topping the list.

Tsongas sees the plight of the older cities as a particularly pressing problem. His native city of Lowell, where he started his political career on the city council, is a prominent example of a once-dynamic northeastern mill city that has suffered from a failing economy and declining population. As a congressman, Tsongas sponsored the first bill to create an urban historical park and, as a result of his efforts, the city of Lowell has received $40 million in federal funds for that purpose.

We drove to Haverhill, where he was given a tour of the restoration work being done on century-old brick buildings that would soon make them suitable for housing and commercial use. Expressing his views on one impact of the energy shortage on blighted cities, Tsongas, who sits on two committees which deal with energy and urban affairs, said: "I think the energy crisis is going to affect the cities positively. If indeed we do end up in a situation where gas rationing is likely, which I think it is, many people living in suburbia may decide for the most part they would be better off in an urban center. For example, it will no longer be feasible for someone living 20 miles into New Hampshire to work in Boston. With rationing, that would simply be impossible. I think the more people begin to realize this, the more interest there will be in returning to urban centers."

With his background on the House Ad Hoc Committee on Energy and his present membership on the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Tsongas is a strong supporter of government-backing of alternative renewable energy resources such as solar, wind, and hydro — both in development and implementation. Speaking at the Haverhill town meeting, Tsongas made a prediction to a still-dubious public on what a refusal to accept the critical nature of the energy situation might lead to: "You can cut back the supply of crude oil and home heating oil and eventually the law of probability will catch up with you. Someone in New Hampshire will literally freeze to death. Then it will be too late."

EARLIER that March day, Tsongas had assessed the energy situation as it relates to President Carter's re-election chances: "It seems to me that if the President has any hopes of surviving politically in New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the winter of '80, he has to have a viable energy policy. My problems with the current energy policy involve: 1) lack of a tough conservation mode, and 2) lack of proper funding for alternative energy sources."

But later, in August, after the President's energy program had been disclosed, Tsongas criticized its fundamental direction: "The Carter program basically puts most of the eggs in the synthetic fuels basket. Synthetic fuels in addition to being pushed at a rate to which technology cannot be pushed, in addition to presenting serious environmental problems, are at best a long-term solution — you're talking about 1990 before you have impact." When asked for a plan that he saw as more effective than that of the President, Tsongas observed: "There is only one way out and that is a serious conservation program: every house in the United States insulated, the banning of the manufacture of gas-guzzling automobiles, the maximization of mass transit, more than token loan guarantees and tax incentives, solar, low-head hydro, solid-waste bio-mass conversion programs — basically the programs that have now been ballyhooed in the Harvard Business School report, Energy Future, which I think is probably the best book put out on the energy issue. We're going to come to that eventually because it is the only reality that exists."

Tsongas is greatly concerned about some of the inherent dangers of nuclear power and, specifically, that of breeder reactors. He pointed out that a plutonium- producing breeder reactor gives opportunities of producing nuclear weapons to anyone who has access to one.

"The danger is this — I'm not so much worried about a breeder in the United States; we can provide enough security — but what happens when you start commercializing the breeder around the world? What happens when you give someone like Idi Amin a breeder reactor? In essence, you're giving him the nuclear bomb. And how would you feel about living in a world where all the Idi Amins had nuclear weapons? It's a sort of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde system — Dr. Jekyll gives you the power and Mr. Hyde blows you up. And I for one don't want to pay that price."

A safe fusion reactor is seen by the senator as a future possibility, but he is quick to add that its full development could be 20 years down the road. "It's what everybody's hopes are pinned on," he said.

LATER, in August, Tsongas reflected on the repercussions of the Three Mile Island incident: "Three Mile Island is clearly something to give one pause. But there is no way out of the nuclear option, at least in the short term. One positive consequence is, I hope, more concern about safety, waste disposal, and those kinds of issues. However, unless there's really a massive commitment to conservation and renewables, you won't get away from nuclear in the mid-term. So, for now, the nuclear option is unhappily there and it's going to remain that way."

Going on to describe the drawbacks of a nuclear moratorium, Tsongas offered this analysis: "Those who urge that you immediately close down every nuclear power plant force you into the coal option. Right now, a lot of time is being spent looking at nuclear drawbacks and no time looking at those of coal. The more people begin to realize what the long-term environmental effects of coal-burning are, the less likely you'll have people following that particular scenario. So all the alternatives, with the exception of conservation and renewables, are unhappy. Nuclear just happens to evoke a certain psychological reaction that coal doesn't, but in terms of dangers and long-term impacts, there's not much of a choice between the two."

DURING his hard-fought campaign, Tsongas received more than token help from Senator Edward Kennedy. Now, the continued presence in the Senate of his senior and better-known fellow Democrat puts Tsongas in a position that some observers feel dwarfs him by comparison. According to a March poll, however, he is the third most popular politician in Massachusetts next to Kennedy and State Attorney General Bellotti. He partially defined his relationship with Kennedy: "Well, it's a unique situation. It has advantages and disadvantages. One obvious advantage vantage is the clout — if he can be persuaded to use it in directions that I'm concerned about, like the situation in South Africa. There isn't too much overlap in terms of our main interests — his are health insurance, the criminal justice system, China — and in many respects we complement each other.

"There's another dimension to him that is unlike that of any other person in the Senate. To recall an incident — I was at a birthday party of a neighbor's child in Washington and one of the parents came up to me and asked, 'Do you know Senator Kennedy?' I said, 'Of course I do. I'm his colleague.' He looked at me and said, 'Wow! I've never met anyone before who knew Senator Kennedy.' You simply have to deal with it on those terms."

TSONGAS operates in a different manner from many other senators. He is often described as low-keyed. Softspoken and convincing, he has a sincerity about him that people find attractive. His manner is characteristically relaxed. He had obviously been suffering from a cold all during St. Patrick's Day. While addressing about a hundred people in Salem, he finally stopped what he was saying, stepped down from the podium, and asked if anyone could spare a cough drop.

His openness has already been noticed during his short term in the Senate. While he has spoken critically of the President's weak efforts to offset the energy disaster, he has just as quickly expressed high praise for Carter's efforts to establish peace in the Middle East.

The freshman senator works hard to keep in touch with the people of his state and to fulfill the promise of accessibility he made repeatedly all through the summer and fall of his election campaign. He averages two weekends a month in his home state, attending town meetings and other events he believes to be important to his understanding of the needs of his constituents. In addition, he tries to read as much of his mail as possible and to be as accessible as he can on a day-to-day basis. A substantial part of his budgetary allocation goes to an economic development staff that works to save or create jobs and to reduce pockets of unemployment in Massachusetts.

Tsongas, who has two daughters — ages two and six — often makes references to the future. His fears about energy are particularly related to this. His concern goes beyond what is five or ten years away, to what will be happening in the 21st century — the- world of our children," he says. What he has to say about this world often seems grim. But he believes it is vital to turn the public mind to a realistic appraisal of energy alternatives now, while options still exist, rather than later, when few choices remain. Defining apathy in face of a worsening energy situation, he concluded a recent meeting by saying: "It's like sitting on a beach knowing that a tidal wave is coming, yet staying on to catch the last of the sunshine."

Tsongas inspecting the Massachusetts urban landscape he thinks will stage a comeback.

William Hill is a junior from theMassachusetts fifth congressional district,which Tsongas served in the House ofRepresentatives.

With his upset victory, Paul Tsongaswould have joined another alumnus,Thomas McIntyre '37, in the Senate — except that McIntyre himself was upset in hisbid for re-election in 1978. McIntyre'sbook on the shifting political tides inWashington, The Fear Brokers, isreviewed in this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureUncle Sam and Mother Dartmouth

November 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Article

ArticleSeeker of the Heroic

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80 -

Article

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

ArticleRags to Riches

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Features

-

Feature

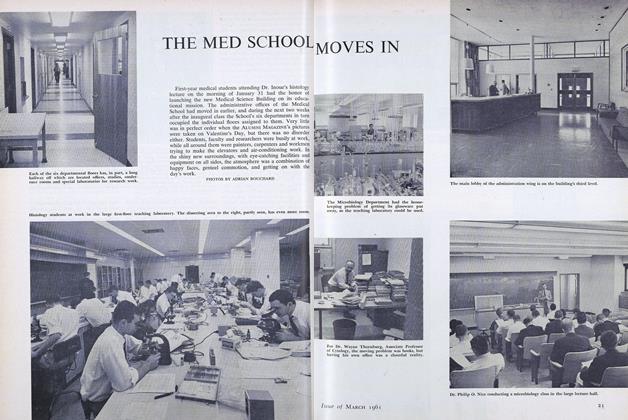

FeatureTHE MED SCHOOL MOVES IN

March 1961 -

Feature

FeatureProfessional Schools

April 1975 -

Cover Story

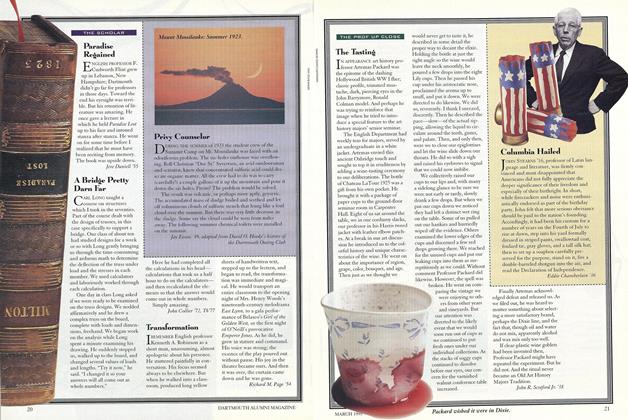

Cover StoryColumbia Hailed

MARCH 1995 By Eddie Chamberlain '36 -

Feature

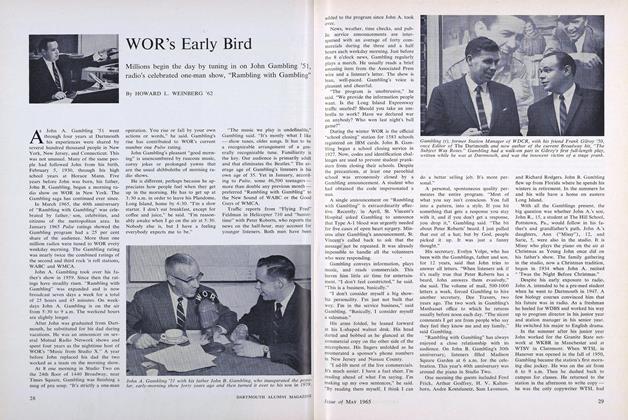

FeatureWOR's Early Bird

MAY 1965 By HOWARD L. WEINBERG '62 -

Feature

FeatureAn All-Time Dartmouth Team

October 1955 By LAURENCE H. BANKART '10 -

Feature

FeatureWhat It's All About

FEBRUARY 1968 By Robert B. Reich '68