EDUCATORS are alarmed about the extent of government involvement in the operation of colleges and universities. At least, that's the impression given by reports in national news magazines and educational journals. It is not that most college officials are reluctant to accept money from federal agencies, but that they are worried about the strings attached, as well as about a wide range of federal law applied to educational institutions.

Time magazine last year cited $15 billion as the amount of annual government aid to U.S. colleges and universities, and listed common complaints about how the funding is administered: too much paperwork, not enough flexibility, unreasonable reporting requirements, and excessive government influence.

This year, a "Report to Alumni/ae" prepared by an organization of college and university editors suggested that "increasing government regulation, with all of its complicating side effects, is the most serious problem facing American higher education." And the Ivy League schools and Stanford, in testimony prepared for the Senate Subcommittee on Education, objected to "the increasing propensity of the federal government to intrude randomly into the day-to-day operations of our colleges and universities and to descend to progressively trivial levels of the educational process."

But what about this Ivy League college? Has the burden imposed by the federal government reached a crisis at Dartmouth? Are there so many strings attached to federal money that education and research are fettered? President Kemeny could not be reached for comment — he was in Washington, working for the government, reporting on nuclear safety — but he has spoken out on the subject in the past. To illustrate the propensity for conflict between regulations promulgated by different agencies, Kemeny has cited an instance when "the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare pushed us to do more to attract minority students, while the Internal Revenue Service was questioning us and trying to prove we were practicing reverse discrimination — leaning over too far to admit minority students.", In his first five- year report, published in 1975, he attributed the increase in the size of Dartmouth's administration (which swelled from 201 members to 267 between 1968 and 1974) partly to the demands of federal requirements. He also said that "federal regulations have added enormously to the demands of record-keeping," and pointed to the example of a major university which "lost vast sums of federal money, not because it was in clear violation of affirmative action rules, but because it was unable to provide the information required by the government."

THE federal government and Dartmouth intersect in two ways. One is in areas of law such as congressional legislation, executive orders, and federal agency guidelines specifying required conduct in order for an institution to receive federal funds or retain its tax-exempt status. The other area of intersection is where federal agencies dispensing money specify how the funds are to be used and accounted for.

The distinction is important, and dissatisfaction with the regulatory rationale and procedures often hinges on what variety of control the critic is chafing under. In the case of law, criticism frequently issues from the assumption that the least government is best (see also Vox in this issue), and that government has no business interfering with educational institutions to the extent that it does. The argument is often driven as much by political as educational theory. Criticism of the regulations associated with funding, particularly research grants, tends to focus on administrative issues.

Bureaucratic misunderstanding of the way educational institutions work is a common complaint, although the severity of the criticism seems to be related to the size of the institution and the amount of money received (the larger the operation, the closer the federal scrutiny). An article in Change magazine argued that "most regulations seem to have been written for hierarchical management systems, not for horizontal college systems where authority is shared. They seem to assume information-processing and accounting techniques that are not uniformly represented in higher education, and this mismatching of regulations with those regulated largely justifies academic dissatisfaction with federal rules." The article added that the "emphasis on procedures and rules rather than on objectives and ends encourages the growing adversary relationship between colleges and government."

ASKED about Dartmouth's experience with federal regulations, Provost Leonard Rieser '44 talked about problems, but not crises. He described the broad area of regulation by . federal law as "at times burdensome," citing a tendency for government agencies to make quantitative, by-the-book judgments, and to apply equally to colleges law formulated originally with corporations in mind. The necessity for elaborate record-keeping is a difficulty, he said, in both academic and budget offices, and the problem is exacerbated by increasing demands. He used affirmative action as an example of a problem — or at least a potential problem — created when different branches of government are responsible for enforcement. The recent switch of responsibility for affirmative action programs from HEW to the Department of Labor "is of particular concern because the people there have no specific background in education." He also noted that in order for Dartmouth to meet its increasing obligations to the government, it employs more people without substantially enhancing its programs.

Rieser described the regulations associated with funding as something one puts up with in order to get the money. In the instance of federal money supplied for student scholarships and financial aid, he suggested that "the regulations seem like a fair deal because we decide whether or not to apply for the funds." His evaluation of the regulations that go along with research money was similar, although he noted that the procedural and auditing requirements are becoming increasingly stringent. The newer regulations, he said, seem to be aimed at what appear to have been abuses of how time and equipment are used at a small number of institutions, but they apply equally to the large majority of institutions that have not abused federal support. This approach seems heavy-handed, but the reasons for increasing controls are understandable. Although many regulations seem excessive, they aren't altogether unwarranted, and in the case of an institution like Dartmouth, where the level of sponsored activity is small compared to an MIT, for instance, the excesses are less of a concern than they might be were more money involved.

His greatest worry about government regulation, Rieser said, is the style of enforcement, not so much in relation to funding as in the area of social legislation. He attributed the problems to a "zealousness for enforcement and threat of extreme sanctions. You can really be put through the hoops." And in some areas, he observed, such as the requirement to change the retirement age from 65 to 70, there is the "basic question of whether or not this is an appropriate act for the federal government." The one certainty of federal legislation and regulation affecting higher education, Rieser added, is that "there recently has been more and more of it. A quarter-century ago there was no regulation in an area in which it now exists."

ACCORDING to the college treasurer, William Davis Jr., $11.2 million of Dartmouth's $80-million gross budget — about 15 per cent of the total — comes from Washington. The Medical School is the principal beneficiary, with about half of its $15-million budget coming from federal funds; at the Thayer School, the amount of government money in the budget is nearing the half-way mark. John Kavanagh, the College's director of sponsored activities (grants for research and educational projects), reported that about 65 per cent of the federal money that comes to the College goes to the medical centers, and that the major federal contributors to research at Dartmouth annually are the National Institutes of Health ($8.3 million), the National Science Foundation ($1.1 million), and the Department of Energy (more than $500,000). Kavanagh pointed out that the amount of federal money coming to Dartmouth is increasing about 10 per cent annually — just keeping pace with inflation. According to John Strohbehn, associate dean of the Thayer School, more than $1 million of the $2.3 million budget there comes from the government in the form of money for grants and contracts. (The Tuck School, however, obtains its outside funding primarily from private sources.)

Davis said that although government auditing requirements and program changes add to the complication of administering the College's finances, "you put up with the headaches because the money is so important." Kavanagh deplored the deterioration of the "sense of partnership" that once existed between colleges and federal agencies, although he maintained that Dartmouth has been "for the most part successful in maintaining a cooperative relationship." He said that even though complying with the wide variety of rules and procedures is a problem here because of the time, expense, and effort involved, and despite the excessive demands for accountability, Dartmouth is not yet at the point where it is "hassled and confronted" by the bureaucrats. "But after 25 or 30 years in the business," Kavanagh added, "the government should be more familiar with how things work at a college or university."

THE government also gives extensive support to the College's $4-million scholarship budget. Under the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant, Dartmouth receives about $600,000 annually, and through the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant, Dartmouth students obtain approximately $600,000 more. In addition, the College also receives $750,000 for work/study programs. Uncle Sam helps out with educational loans, too — $300,000 under the National Direct Loan Program, and $1.2 million in guaranteed student aid (federally insured and supported state loan programs).

Harland Hoisington Jr. '48, director of financial aid, said his office spends a disproportionate amount of time administering federal money. He mentioned complex and extensive paperwork, inefficient government administration of some programs, and a tendency for regulations to be written with the worst offenders in mind. He also pointed out that program procedures are constantly changing — by the time a set of regulations is issued, revised, and implemented by college administrators, the law is often rewritten and new guidelines spelled out. There have, however, been some recent improvements, Hoisington noted. The Carter administration is apparently making efforts to streamline the administration of some programs, and there has been some consolidation of reporting procedures. Along with several other administrators, Hoisington seemed to think that the money received more than makes up for the headaches inherent in administering it.

Administrators at Thayer School and the Medical School seemed particularly concerned about the strings attached to federal money. Strohbehn said that federal auditors recently took a close look at Thayer, and that "the auditors' perception of how to carry out a research program is different from ours." Strohbehn reported that Dean Carl Long has suggested that changes might have to be made in order to supply what the government seems to want. For example, the auditors wanted statements about who monitors how: faculty members spend their time. "No one monitors faculty time," Strohbehn said,' "That's not the way it works. They wanted to be able to audit how much time faculty members spend on research, and all we could do was give them the teaching schedule to show there was more than enough time left for professors to work on their grants. It's a very competitive environment, and most researchers put in far more time than they are paid for."

Dr. Philip Nice, the dean in charge of academic affairs at the Medical School, said that coping with government regulation "is our whole life. That's how we run our operation, and we deal with it every day." He pointed out that because some of the Medical School buildings were partially constructed with federal money, their size and use and even the number of students admitted is regulated to some extent by the government. When the buildings were put up, Nice explained, the government was encouraging medical schools to expand. Last year, however, HEW announced that there are too many doctors, and medical schools may soon be encouraged to cut back. The amount of capitation money available — aid based on the number of students enrolled — has been waning, and has been manipulated, Nice suggested, in troublesome ways. There was, for example, the controversial one-year requirement that in order to receive capitation money at all, medical schools would have to admit a certain number of American transfer students who were studying medicine abroad. In addition, Nice said, in order to "drive students into the National Health Service program," in which students provide a year of practice in underserved areas in exchange for a year of financial support in school, the government has eliminated substantial amounts of federal scholarship money and has upped interest rates for loan programs. Nice characterized much of this government involvement in education as "intrusive."

THE most controversial piece of social regulation affecting colleges is affirmative action. Margaret Bonz, who is in charge of the program at Dartmouth, said that the idea of "actually taking affirmative action" to employ women and minorities at Dartmouth isn't so much a requirement imposed from above by the federal government, as it is a sincere commitment of the College. The required record-keeping and reporting has so far been minimal, she claimed, although there has been some concern among affirmative action officers nationally that the Department of Labor might be more bureaucratic in its administration of the program than HEW was. "What I do for the federal government," Bonz said, "consists of one annual report, which is minimal. We do have to keep records on hand, however, to demonstrate our compliance if we are asked to, and different branches of government disagree about how, and for how long, the records are to be kept." Much of the information collected on recruitment, hiring, salaries, and promotion is information that has institutional uses aside from affirmative action, she added. Although Bonz said she is annoyed by bureaucratic requirements that "waste time and detract from what this business is supposed to be about," she noted a history of good relations between Dartmouth and officials at HEW, "who have viewed us as responsible and committed." Asked how her job would be different if affirmative action were not federally mandated, Bonz replied that "for those few areas within the College where there is resistance, the federal requirement is an important stick."

Strohbehn said that at the Thayer School he finds affirmative action "particularly difficult," not because of disagreement with the objectives, but because of the nature of the applicant pool. "We would love to hire blacks and women, but they just aren't out there. We've increased our recruiting budget for advertising from hundreds of dollars to thousands of dollars, but we don't feel that necessarily gets us a better faculty," he argued. "As bad as it may sound, the 'old boy network' seems to work best for us. In our case, affirmative action is an example of a federal regulation that has required time and money without accomplishing much."

SEAVER Peters '54, director of athletics, commented on both affirmative action and the controversial Title IX requirements for equal athletic opportunities for women. He applauded the goals of both programs, but described their administration as often time-consuming and expensive. He suggested that affirmative action requirements may be occasionally unfair to an institution's employees applying for advancement, as well as to outside candidates who might be invited to interviews primarily because of an administrator's desire to make a recruiting report look good, but he also cited some practical advantages. "In many ways, the requirements have been good for me, because I tend to be impulsive. Affirmative action has forced us to make a thorough search before hiring someone, and that has resulted in a stronger staff." Peters did express frustration, however, in looking at some athletic powerhouses that announce a coaching vacancy one day and hire the person they want the next day, in apparent disregard of the rules.

Peters was asked if Title IX requirements have forced the athletic department to make changes it might not have made otherwise. He said the requirements have "forced us to accelerate the pace and growth of women's athletics, but I'd like to think we'd be there anyway, although not as quickly." He maintained that the College is in compliance with the regulations, although he pointed out that many schools will find it financially impossible to operate under some of the guidelines. The impact on Dartmouth's athletic budget has been that the department concentrates on funding athletic programs — creating and expanding sports for women — instead of putting money into facilities.

Some problems with Title IX, Peters said, are differences in enforcement from region to region, and somewhat unrealistic guidelines. The tentative guidelines put out last fall, for example, were based strictly on a computation of equal money to be spent per male and female participant, without any appreciation of the different costs of different sports. Football, for example, costs much more per participant than women's volleyball. HEW also said that recruiting budgets for men's and women's sports had to be taken into account when per capita expenditures are figured, but women's athletic association rules prohibit reimbursing coaches for expenditures incurred on recruiting trips.

DEAN Alvin Richard chairs the committee charged with making sure that Dartmouth facilities and programs are accessible to handicapped individuals. Richard said he felt good about the College's record in keeping both the letter and the spirit of the law. The committee has drawn up a three-phase plan for complying with a set of target dates issued by HEW, extending from 1977 through mid- 1980, by which time all facilities designated should in fact be accessible. So far, the deadlines have all been met. The first phase of the plan, which cost over $90,000 of College funds to implement, made important facilities — the library, the dining hall, a dormitory, and the Hopkins Center — accessible, and also included relatively simple modifications such as curb cuts around the campus. (Not every college building needs structural modifications. It sometimes suffices to make a program or service available by bringing it outside the building to the handicapped individuals who want or need it.) Phases two and three included plans for desirable, but not urgent, modifications, and their projected cost is $181,000.

The most frequent criticisms of the accessibility regulations concern the relationship between the expense of modifying buildings and the number of people who actually need the changes, and also the ambiguity of the word handicapped, which is applied to a wide variety of disabilities, including alcoholism. Richards declined to guess how many handicapped individuals attend or work for the College — for various reasons not all such persons identify themselves — although he guessed that the number is small, primarily because of Hanover's winter environment and hilly terrain. Although Dartmouth's self-evaluation report has to be available at all times for federal scrutiny, Richard said, there are no other reports or inspections mandated by the regulations. "Dartmouth is fortunate in its ability to meet the requirements," he added. "The only hassle is that this is yet another federal requirement, and an expensive one that many institutions are hard pressed to deal with."

BOTH businesses and educational institutions have been critical of OSHA — the Occupational Safety and Health Act. According to the director of Buildings and Grounds, Richard Plummer '54, the College is taking a pragmatic approach to compliance. "We are primarily concerned with the safety of our employees," Plummer said. "To comply fully with OSHA would require a great deal of money. The original regulations were two inches thick." Plummer reported that violations at the College are not serious, and that the situation is improving every year. Buildings and Grounds has a safety officer and safety committee, and each year Plummer writes a safety report for college, not government, use. The only documents prepared for the government are accident reports submitted to a state agency by the personnel office. Plummer said the biggest problem with OSHA has been in research labs and at the Medical School, which has been twice inspected and cited as the result of an employee complaint.

Clarence Burrill, director of employee relations, has to deal with as many government agencies and regulations as anyone at the College. The list he produced "is by no means exhaustive," he said, but it includes 17 categories of legislation and regulation, ranging from wage-and-hour laws to civil rights legislation. Burrill said that "a very substantial amount of our time is spent interpreting these regulations, adjusting to changes, and making sure we are in compliance." He also pointed to "a proliferation of regulations over the past five years," — regulations formulated with commercial organizations in mind, and recently applied to colleges. "But they lay it on an educational institution much harder than they do on industry," Burrill claimed.

THE trouble with "excessive government regulation," a recent report observed, is that it produces bureaucracy both in Washington and on campuses, it wastes time and money, it threatens institutional autonomy, and it erodes what has been "a long and mutually productive partnership between the federal government and higher education." The distinction between excessive and reasonable regulation remains open, however. Frederick Edelstein, a policy analyst for the Office of Education, wrote in the agency's American Education magazine this year, "To most individuals and organizations, regulations appear as restrictive and requiring too much paperwork. Rarely is the regulation seen as a protector of an individual's or a group's rights and as a guide to how programs are to be structured and directed. Maybe to some a regulation is an evil, but if programs established by a statute are to be implemented, it is a necessary one. In the end, the costs are outweighed by the benefits." Kemeny conceded some practical benefits in his five- year report: " ... the new federal regulations have contributed to better management practices. The College has become more efficient and is more responsive to the needs and aspirations of its employees."

It might be argued that colleges themselves have to share part of the blame for creating the regulated environment they now find themselves in. Campuses have long been a locus for promoting social change, but many educational institutions have been reluctant to implement some of the social changes required by legislation. Princeton President William Bowen remarked recently to a reporter that "in athletics, there might well be no Title IX today if colleges and universities had done all they should to support women's programs. They fell short and this has produced regulatory pressures that are controversial and troubling. The same is true of affirmative action. ... The extent to which external pressures are brought depends more often than not on how well you have done your own job." When Bowen was asked how a university can avoid becoming overly dependent on federal money, and how it can avoid having its freedom jeopardized, he replied, "Always be prepared to say no when your essential principles are threatened."

Despite his beneficence and good intentions, Uncle Sam's presence on campuses has indeed become increasingly evident and increasingly disturbing. At Dartmouth, however, there is not much evidence that essential principles have been threatened. The description of government regulation as the "most serious problem facing higher education" seems overblown, particularly in the case of an institution whose main concern is undergraduate education. Finances are likely to be a more pressing problem. And because obtaining adequate funding is so important, the consensus at Dartmouth is that the frustrations of dealing with the government are more than offset by the money the government supplies. Although there appears to be cause for concern here about government regulation, there does not yet seem to be reason for alarm.

Government funds and government regulations

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIt's Where We're Coming From, Citizens

November 1979 By Jeffrey Hart -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill -

Article

ArticleSeeker of the Heroic

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80 -

Article

ArticleGadfly

November 1979 By M.B.R -

Article

ArticleA Little More Anarchy, Please

November 1979 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

ArticleRags to Riches

November 1979 By Beth Baron '80

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureES 21

January 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

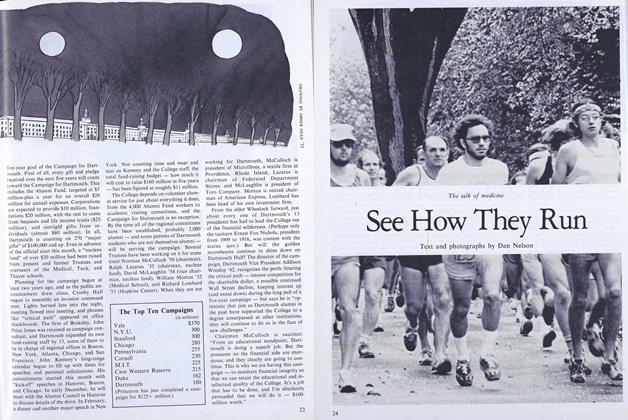

FeatureSee How They Run

NOV. 1977 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Article

ArticleA Journey: Five days to Big Rapids

September 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureTemples, Turtles and Fat Boys

September 1979 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

JULY 1959 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Frost 1896

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureBURNLEY

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureBIG JUMP

Winter 1993 By David Bradley ’38 -

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

MARCH • 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1956 By WILLIAM FREDERICK BEHRENS '56