In this imperfect world, alas, poets often are required to function prosaically. Frequently, nowadays at least, they must become teachers; sometimes, like the rest of us, they may also become parents, taxpayers, tennis players, doctors, insurance executives, baseball fans, or psychotics. Most often, however, they become literary critics; they seem to take naturally to that. And becoming such, they are compelled, of course, to communicate in the language and modes of prose, not poetry.

Sometimes they write reviews of other poets' works, sometimes they try to become the acknowledged legislators of their own works (vide Eliot's notes to The Waste Land), or sometimes, if they reach some degree of eminence, they expound the beauties and mysteries of their art from public platforms. Though most of them reason not the need, some poets tend to resent the necessity for it. They tend, perhaps unconsciously, to segregate; their poems are one thing, their prose essays quite another, separate and decidedly unequal. And so in their essays and public speeches they seem, now and again, to become a shade too cantankerous, quarrelsome, crotchety, as if to suggest that to have to revert to prose to describe poetry is somehow to stoop.

Not so for Richard Eberhart. For him there is no stooping. For he has the wit - to say nothing of the erudition - to understand that like poetry literary criticism, too, is "an endless effort to find and evoke meanings for your life as it goes by and you try to catch it, elusive, in the shortness of your stay on earth."

The meanings Eberhart has found are splendidly evoked in this collection of 23 of his previously published critical studies, prose essays, and fugitive pieces. Temporally, they span something over three decades of writing and lecturing, the earliest having been published in 1947, the most recent in 1978. They are nothing if not eclectic. Some are in the language of formal discourse: closely reasoned addresses delivered on various ceremonial occasions; analytical essays and reviews written for literary journals; close readings of other poets' poems. Others are less formal: reminiscences of the poet's salad days at Cambridge University; recollections of his personal contacts with whole pantheons of fellow poets, with Yeats or Frost, Stevens or Empson, Roethke or Dylan Thomas; autobiographical excursions (happily, whole big revelatory paragraphs of those). And still others are merely chatty: literary anecdotes (the Harvard poet John Wheelwright customarily enlivened literary cocktail parties in Cambridge by solemnly worming his way across a crowded room beneath the carpet); informal, catch-as-catch-can conversations about poetry in recorded interviews; and literary gossip (which is none the less interesting for being so since, it affords an occasional hint of the elbowing and in-fighting that sometimes occurs on the steps to Parnassus). The book has its draughts of ambrosia, but there is a lot of good tangy small beer as well.

It is not a tidy book. Eberhart has no rage to order. That may throw some people off, but not those acquainted, with the disorder into which many other poets seem to fall the minute they begin to discuss Poetry with a capital "PCompared to most, Eberhart is a model of economy and lucidity. Moreover, if the book is untidy, it is because life itself is untidy and because poetry, like life, is rich with contradiction and paradox. As James Dickey writes in the foreword to the book, "All is not order in either the prose or poetry of Richard Eberhart. He is beyond that, and he, in his work, passes beyond any neatness. He has the gift of life, as well as the gift of the library."

Amid the patterns of diversity, nevertheless, some threads run true. Early or late, beginning' middle, or end, Eberhart holds to the in- spirational theory of poetry. Here he is in 1947: If I have a theory of poetry, it is that poetry is a gift, a gift of the gods if you will, or a gift of nature, but at any rate it is not something that can be' achieved by the utmost of study." And here he is more than 25 years later, in 1973: "I have, I think, somewhat unusual ideas about the creative act. 1 have never understood it in my entire life and I don't understand it now. But I think of the creation of a poem as an in- spirational thing at its best It is as if it were a gift of the gods, and as if the personality of the poet were a vane upon which a wind, a spiritual wind blows, so that in a sense the whole being is used by the poem." Most poets no doubt find that theory uncongenial in this cerebral age, but in holding to it Eberhart joins a distinguished company: Shelley, Blake, D. H. Lawrence, Wordsworth, not to mention the ancient Greeks who originated it.

Eberhart returns to the Greeks, too, for another of his fundaments. "I believe," he says, "that poetry comes out of suffering." Some poets suffer physically, he points out — Pope, Cowper, Smart — some from observing other human beings suffer — Whitman in the Civil War hospitals — but most poets "suffer in the imagination. It is impossible to conceive of great poetry being written without a knowledge of suffering." Wisdom through suffering, joy through despair, innocence through experience: these are "the old truisms ... the old opposites," as Eberhart calls them. And in perceiving the profound human wisdom which they embody, Eberhart joins an even more distinguished body, among others Shakespeare and the Greek tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides.

The final . thread is enthusiasm. That, if anything, is the informing spirit of the book. The enthusiasm for experience in all its forms, for poetry, for language, for ideas, in a word for life. Eberhart enjoys what he does, he likes what he talks about. He has the teacher's innate love of teaching, of explaining, of explicating, of testing ideas, throwing them out, observing their shapes, contours, sizes, and hues. His essays show it; they are suffused with the exuberance of a restless, inquiring, testing mind. James Dickey again: "Eberhart's critical work is essentially an affirmation. ... His generosity toward poets and poetry proceeds from ... an overwhelming acceptance of and delight in life. He is closed off to nothing."

OF POETRY AND POETSBy Richard Eberhart '26Illinois, 1979. 312 pp. $15

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature'We will all make whoopee'

June 1979 By Dick Holbrook -

Feature

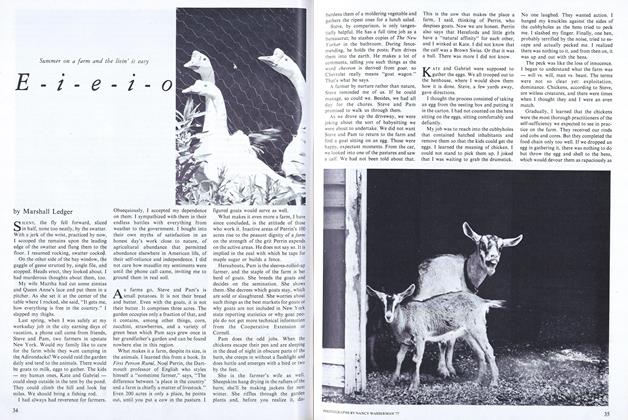

FeatureE – i – e – i – o

June 1979 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

FeatureExit with a Flourish

June 1979 By Beverly Foster -

Feature

FeatureEncouraging growth, affirming the educational process

June 1979 By Robert Kilmarx -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1979 By James L. Farley -

Article

Article'Radical' with a Cause

June 1979 By Tim Taylor

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksGRAY MATTERS, A NOVEL.

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTelling Tales

APRIL 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFear of Flying, Combat in the Forecourt

October 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTurning Pro: Undergraduate writers break into print

OCTOBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksPassable

DECEMBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksHERMAN MELVILLE

December 1949 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

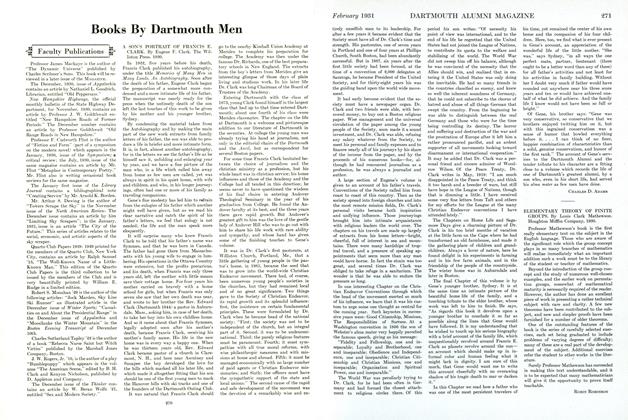

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

January 1920 By c. c. s. -

Books

BooksThe Crookshaven Murder

MARCH, 1928 By F. L. C. -

Books

BooksIT'S A WISE PARENT,

November 1945 By M. D. F. -

Books

BooksSKELETON OF LIGHT.

December 1961 By RICHARD EBERHART '26 -

Books

BooksELEMENTARY THEORY OP FINITE GROUPS.

February, 1931 By Robin Robinson