For almost 200 years, Mary Wollstonecraft has occupied a secure niche in the pantheon of literary and intellectual history. Early English feminist, novelist, social rebel, author of the Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), wife of the radical 18th-century social philosopher William Godwin, mother of Mary Godwin (who later married Percy Bysshe Shelley): These are among the facts we tend to recall about this remarkable woman.

But they are facts only, the kind of disembodied data that get sifted out by history and encapsulated in reference books and biographies, important enough in their way, of course, but the stuff of which icons are made, not people. What of the human being behind the icon? What of Mary Wollstonecraft, the thinking, feeling, flesh-and-blood woman? Can we know anything of her now, 200 years later? Yes, a good deal perhaps. But only if we are prepared to turn from facts to feelings, from biographical data to autobiographical revelation. For that kind of insight, what better source than her letters?

And here they are, scrupulously edited and collected for the first time, 346 of Mary Wollstonecraft's letters, the first written in 1773, when she was 14 years old, the final one in 1797, only 11 days before she died of postpartum puerperal fever. Like most personal letters, they are occasional writings dashed off hurriedly, one here one there, to friend, sister, lover, husband, as the occasion offered or the spirit moved. They are the more interesting for being unliterary and spontaneous; the more revealing for being impulsive and unself- conscious. And what they reveal, at least to me, is a very ordinary thing about a very extraordinary woman. Mary Wollstonecraft the woman - not the icon, not the symbol, not the rallying point for the feminist cause, but the person - was just as inconsistent as any other human being. She embodied, that is, the most human of all human traits: paradox. She was only part feminist steel; the other part was 18th-century crinoline.

Of an intensely religious, indeed theistic, nature, she nevertheless lived a good part of her life by the austere tenets of rationalism - but at how great a cost these letters reveal. For all her views of women as something other than mere objects of men's lusts - or in Lord Chesterfield's obscene phrase, "only children of a larger growth" - we sense in the letters with what enthusiasm she allowed herself to become the mistress of an almost archetypal 18th- century womanizer who abandoned her after she had borne him a daughter. Though she wrote several rigorously argued books on controversial issues - the education of daughters, women's rights, the French Revolution - her scholarship was neither systematic nor, in some cases, even accurate. The inconsistencies were many.

But the point is not that Mary Woll- stonecraft was somehow spineless, least of all that she was a hypocrite who advocated one position in her books but lived quite another in her life. The point is simply that she was a human being. That is, she was a paradox.

In spite of the complexities, however, one thread, one consistent thread, runs through it all. From start to finish the letters disclose her fierce desire for independence. "I am not fond of grovelling," she wrote early on, well before she set out to carve a career in London. And it was precisely this innate independence which "provided the underpinning for her life's work," as the editor of these letters concludes, and impelled her to envision in her books "a society in which the inalienable rights of women would be recognized as essential to the proper fulfillment of all mankind."

It was this independence, too, her unshakable sense of self-worth, which allowed her to flout the received opinions of her own age and abide the judgment of history with equanimity. The final letter in this book sums it up: "Those who are bold enough to advance before the age they live in, and to throw off, by the force of their own minds, the prejudices which the maturing reason of the world will in time disavow, must learn to brave censure. We ought not to be too anxious respecting the opinions of others. ... I am easy with regard to the opinions of the best part of mankind - I rest on my own."

COLLECTED LETTERSOF MARY WOLLSTONECRAFTEdited by Ralph Wardle '31Cornell, 1979. 439 pp. $25

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

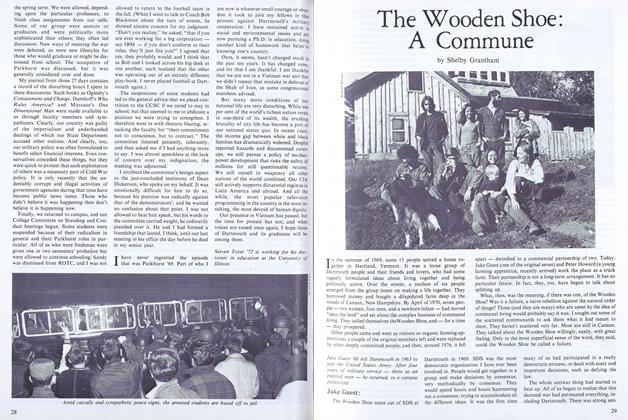

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWhen They Resisted

May 1979 By Steven E. Tozer -

Feature

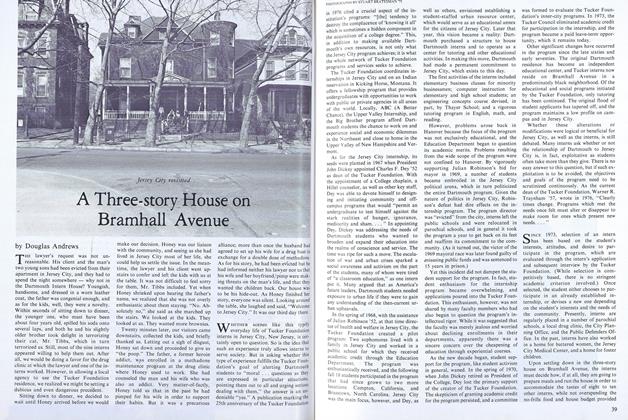

FeatureA Three-story House on Bramhall Avenue

May 1979 By Douglas Andrews -

Article

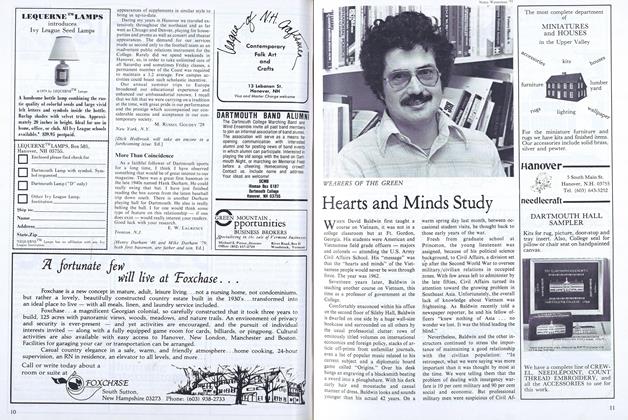

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

May 1979 By WILLIAM A. CARTER -

Article

ArticleJudicial Clerk

May 1979 By M.B.R.

ROBERT H. ROSS '38

-

Books

BooksTHE FOUR SEASONS OF SUCCESS.

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksProfligate Father, Square Son

April 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksCredit to the Age

June 1976 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFacing the Great Issues

MARCH 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFear of Flying, Combat in the Forecourt

October 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Article

-

Article

ArticleNOTES

January, 1923 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

January 1950 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1951 By DONALD D. MCCUAIG '54 -

Article

ArticleArt Thibodeau Stricken

November 1951 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 1905

June 1916 By Lafayette R. Chamberlin -

Article

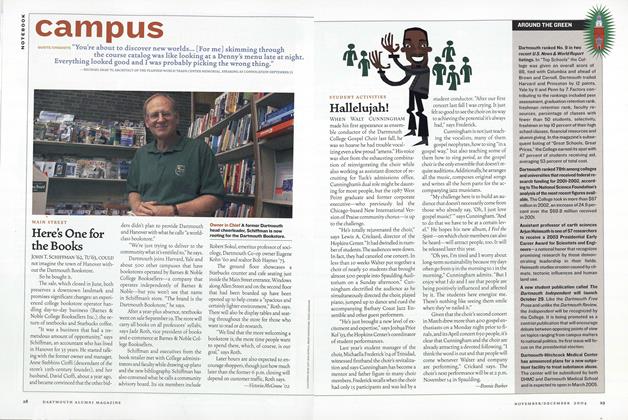

ArticleHere's One For The Books

Nov/Dec 2004 By Victoria McGrane '02