MOVING PICTURES:The Memories of a Hollywood Princeby Budd Schulberg '36Stein and Day, 1981. 501 pp. $16.95

First, it's a good book, a really good book. Schulberg has never been a mass production bookman, but as Tracy said of Hepburn - what there is, is "cherce."

I expected the book to be "special" to a narrow audience of "Early American Cinema" buffs (including me). And of course it is, going from the primitive sunlighted sets on New York loft-building roofs to the acres of glass stages of the vast Hollywood dream factories, with the exfurrier arcade operators growing in less than a decade into the fabled movie moguls. And the book delivers on this expectation fascinatingly, in fact. But into the telling Schulberg weaves a dozen or so additional "plot lines" of universal appeal and interest.

Of course, as the subtitle indicates, the framework is an early-years autobiography of a quiet, shy boy growing through adolescence in a swirling combination of homey and fantasy environments. But, actually, to unload a phrase I have been waiting a long time to use, it's an "Autobiography About Other People." And what people! First, his legendary parents, Benjamin P. and Adeline (Jaffe) Schulberg, children of recent immigrants from Russia and childhood sweethearts in the sweaty New York ghetto of Rivington Street. B. P. (for Perceval!) was tall, slender, and blond, with slightly bulging blue eyes, gracious but tough. Having become a "scenario writer" and publicist for the pioneer filmmaker Edwin S. Porter (The Great TrainRobbery), B. P. was, at the age of 22, already making a luxury income when Budd was born in 1914, but he was soon to join the diminutive giant Adolph Zucker and move to the West Coast, where he would earn a half million dollars a year, plus bonuses, as head of Hollywood production under pioneer Jesse Lasky at Paramount Pictures. He was brilliant, charming, erudite, a concerned father, and devotedly (gambling and drinking) selfdestructive.

Ad was small and adorable, sensitive but matriarch-strong. "Never a hugger," Budd remembers, "she reached out to our minds, loving us vicariously for the intellectual and creative accomplishments she encouraged with the persistence of a coxswain exhorting his crew to the finish line. ..." Ad was a culture-absorbing, social-activist Jewish mother-hen who, after the inevitable eventual divorce, started and built one of the most successful entities in that hardestbitten of Hollywood mafia, the talent agencies.

Budd's Hollywood boyhood was a Rubik's Cube of contrasts, symbolized by a kid on a bike being waved to by Clara Bow in her red roadster, while he peddled soft drinks to the construction workers along Wilshire Boulevard. He was eking out his five dollars a week allowance, but he still inherited his father's discarded Duesenberg. He edited the school paper at L.A. High and became tennis champion of the burgeoning Malibu colony. And always, pushed by B. P. and Ad, he wrote. He and his inseparable chum and neighbor Maurice Rapf '35 had the Paramount (Schulberg) and MGM (Rapf) "studes" for playgrounds, but they regarded them as no more glamorous than their hobbies of radio and racing pigeons. And both fasted in the midst of plenty, being "desperately afraid of girls."

Of course, the book is loaded with inside glimpses of the famous and the infamous, the sung and the unsung: these up-from- the-nickelodeon moguls and their tribes; the weeping bully Louis B. Mayer and his anointed genius, Irving Thalberg; the small, cool Adolph Zucker and his ungrateful Mary Pickford; B. P.'s boss Jesse Lasky; the wild man of Broadway Lewis J. Zeleznick (his renamed son David was "the best assistant B. P. ever had") who during an intermittent period of chaos at Universal Studios moved into a vacant office and had his name painted on the door as General Manager; and watching over all, that Sammy of the Synagogues Rabbi Magnin, who excommunicated Budd for hilarious cause.

Around them are those starry figures of my own Nugget nights when Bill Cunningham played three-finger piano under the hail of re-recycled peanuts: B. P.s prime "discoveries" Clara Bow of It and Gary Cooper of Wings who, with Freddie March, was the Babe Ruth of boudoir blackbelters. Harry Rapf matched B. P.'s discoveries with his own: Joan Crawford and the wonderful Beery-Dressier team, Marlene Dietrich and Joe Sternberg; Archie Leach become Cary Grant, and so on. Dartmouth crops up often in Budd's early years, with Walter Wanger, Gene Markey, Percy Marks, Rudy Pacht, and Maurice Rapf's kid brother Matty. The book ends at the beginning of the Depression and the forecast of Trouble in Paradise (and doom for B. P.), with the entire Schulberg-Jaffe family, complete with studio entourage, at the old Santa Fe station to see Budd off for Hanover. "I was already homesick for Malibu and Lorraine," he remembers, "but as the train began to pull out and I leaned from the Pullman platform to wave and keep waving, I could see Mother standing to one side with Sonya and Stuart, Father standing apart waving his cigar, and I knew that never again would there be a home in Windsor Square or a Malibu beach house where all of us would be living together. I watched the group, all thirty of them, my loving, envious, conflicted, extended family fall away, as seen through the lens of a camera slowly irising down to a small circle, a dot, to nothing." The book is a solidly craftsmanlike job of writing; clear, clean, and (rare in this day) comfortably linear. Candid but fair, and utterly free of self-indulgence. In the awful current phrase, it's a "good read." The story ended too early for me, and I'll hope that Budd continues the saga.

CHARLES PALMER '23

Cap Palmer, executive producer forParthenon Pictures and former MetroGoldwyn-Mayer executive, has writtenmagazine fiction, screen plays, and morethan a dozen books, among them Case History of a Movie, of which Dore Scharywas co-author.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Now we had to go in different directions"

November 1981 By Rob Eshman -

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

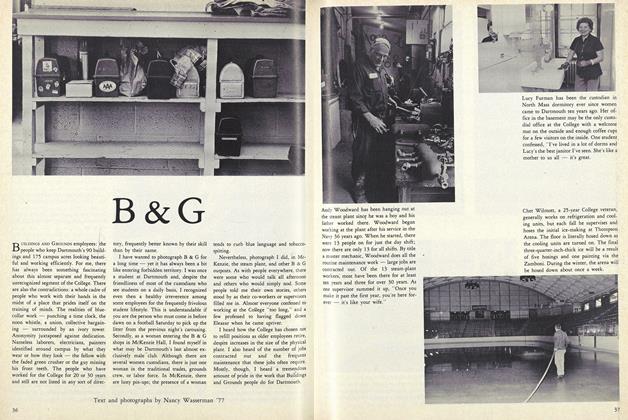

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn

Robert H. Ross '38

-

Books

BooksFRANK PEARCE STURM. HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND COLLECTED WORK.

OCTOBER 1969 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksFacing the Great Issues

MARCH 1978 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Article

ArticleSteel and Crinoline

May 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksMountain Man

October 1979 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksTurning Pro: Undergraduate writers break into print

OCTOBER 1981 By Robert H. Ross '38 -

Books

BooksThe Alchemist

OCTOBER, 1908 By Robert H. Ross '38

Books

-

Books

BooksMASSACHUSETTS PRACTICE. VOLUME 28. CONVEYANCING WITH FORMS.

JUNE 1968 By DOUGLAS L. LEY '35 -

Books

BooksMelodies Lingering On

September 1980 By H. Wiley Hitchcock '44 -

Books

BooksMaintaining a United Front

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksHOW TO CATCH A CROCODILE.

MARCH 1965 By R. J. B. -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN WOMAN

June 1944 By Ralph P. Holben -

Books

BooksImages of Light, Landscapes of the Mind

May 1976 By SAMUEL FRENCH MORSE '36