LIFE without adventure is living death," John Ledyard might have said. The observation, however, belongs to Ledyard's spiritual kin Michael Winn '73, whose wilderness yearnings run every bit as deep as did Ledyard's. Those who subscribe to the belief that the world's fron- tiers have all been conquered should talk it over with Winn, who continues to uncover and surmount one natural challenge after another.

Winn quotes St. Augustine's admonition that "the world is a book and those who do not travel read only a page," but he is hardly content with safe familiar territory or luxury accommodations. His destinations are the places rarely or never before seen by Westerners, and he frequently makes his way into the world's remote corners by rafting down rivers that are both uncharted and untamed.

"Rivers are the last frontier on the earth's surface to be explored," claims the red-bearded Winn, whose accounts and photographs of his meanderings have appeared in Time, Newsweek, People,Parade, Geo, and Saturday Review. "Everything else has been climbed, hiked, or sailed. I'm part of a small group of people hooked on the 'floatable feast,' the quest for new adventures on new rivers."

He has learned that waterways can take an explorer to areas where he could not walk. That includes the lower reaches of Ethiopia's Omo River. Winn and his expedition rafted 150 miles further downstream (past 2,000 hippos) than any non-native had ever gone before, and they were the first white men ever seen by most of the region's inhabitants, members of the Bodi and Mursi tribes.

The footloose Winn has conducted more than 30 raft trips on the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, has navigated the Wadi Zabid in North Yemen, and has trekked down waterways in Alaska and British Columbia. On the drawing board are plans to raft down the Padmas River in Borneo, the Indus in the Pakistani Himalayas, and the upper Yangtze off the Tibetan plateau in western China.

None of this would seem to be beyond Winn's ken. Perhaps his greatest talent is his ability to wheedle his way across borders few foreigners manage to penetrate. Ethiopia's Reign of Red Terror, a bloody clash between two Marxist factions, broke out while he was in the country. While other foreign journalists were kicked out of the country, Winn, who speaks fluent Amharic, masked his identity as a newsman and stayed in. He witnessed a totally anarchic state of affairs in which machine guns strafed streets and villagers "didn't know who was killing whom." Twice he was tossed into prison, once after being framed on a blackmarketing charge and once as a suspected C.I.A. agent.

The man who professes "the challenge of living in our mechanized society is to live fearlessly, to kill the boredom within ourselves," has also seen the inside of jail cells in Nigeria and North Yemen, where outsiders with red beards and cameras are viewed with distrust. Winn thinks that North Yemen, which only a handful of foreigners have explored as completely as he has, may be the most fascinating of the 50 countries he's visited. "It's an ancient 2,500-year-old kingdom, preserved in its original form, with stone castles sometimes ten stories high," he explains, 'it's the only truly Islamic republic in the Middle East and is where Iran was 20 years ago. With its mountains and isolation, it's also the Tibet of the region. And its terrace gardens are the agricultural marvel of the world."

His adventures do not always occur in an aqueous element. He has climbed Nabl' Shayub, the 13,000-foot mountain in North Yemen that is the highest peak in the Middle East. He's also reached the top of 20,000-foot Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya. After a relapse of hepatitis at the 15,000-foot level, he meditated for 24 hours until the fever passed and then continued to the summit. "I like high places," he notes. "I'm often seen jumping off bridges, waterfalls, and high cliffs into rivers. Skydiving will be my next sport."

These outdoor experiences are more than mere personal thrill-seeking. On one trip through the Grand Canyon ("my real home, the natural touchstone in my life"), he was a guide for 45 international diplomats, including a Turkish ambassador who "wanted to know if we were really going to sleep on the ground." Winn remembers it as "one of the most harmonious trips I've ever known. The whole idea was to break down personal barriers." It was an idea that worked. A political pow-wow between these men from 16 countries near the end of the trip was, they told Winn, the best conference they'd had. "After what they'd shared together they could be honest." he recalls. "They felt they could yell and scream at each other and still be friends."

Winn, San Francisco-born and now a New York resident, married an Ethiopian woman in 1975 to keep her from being deported to a war area. "It started as legal aid, moved into love, failed, and ended up as friendship," is his synopsis of the situation. The relationship undoubtedly contributed to his interest in Third World politics, and he has combined derring-do with keen prognostication. While other journalists looked elsewhere, Winn held to the belief that Robert Mugabe would eventually be welcomed as the leader of Zim- babwe Rhodesia. He spent two months with the exiled Mugabe in Mozambique, compiling interviews that were highly coveted when Mugabe returned to Salisbury.

MICHAEL WINN was a Russian major at Dartmouth and completed a senior fellowship on Vladimir Nabokov and Gogol. On one visit to Switzerland he dropped by Nabokov's Montreux home and, after establishing his knowledge of the master's work, was greeted warmly for several hours.

After graduation he expatriated for a year in Nice and Corsica to learn French. On his return to the United States he became, at 23, a publicity director for a New York publisher, representing such authors as John Jakes, whose Kent Family Chronicles have sold 30 million copies. With tongue only slightly in cheek, Winn talks about his own desire to write The Great Siberian-American Novel "on the effects of deprivation on the human imagination, with Siberia as a metaphor for isolation."

He takes more chances than might seem advisable, and perhaps he has in fact laughed in the face of danger; he is certainly one of the few Dartmouth graduates to have been attacked by a crocodile. Winn watched for several tense moments on the Omo until the reptile "decided we were bigger than he was" and pursued dinner elsewhere. "One of the reasons I'm not afraid is because I've always been so lucky," Winn says with a smile. "I'm not suicidal, but it's all a calculated risk. I personally feel safer in the remotest part of the world with so-called dangerous natives than I do crossing a street in New York. There's no point in wondering about when you're gonna die. Follow your intuition and it will all happen naturally." Alluding again to his beloved Grand Canyon, he says that "when it's time to die, I plan to drop my body off Point Sublime on the North Rim."

His literary background is strong, he is a student of mythology, and he is a practitioner of meditation and Tantric Yoga. A most unusual hybrid of these influences can be heard in Michael Winn's conversation. "The oldest known myth in the world is the Hindu myth of 'eternal return': the river flows in an endless cycle to its source in the ocean, where all rivers become one, then back to the sky and mountains where each follows an individual path once again," he informs us. "The human mind is like a river you have to skillfully guide your mind through life's rapids. The trick is to avoid getting hung up on the rocks, to relax and let your mind flow on its most natural course."

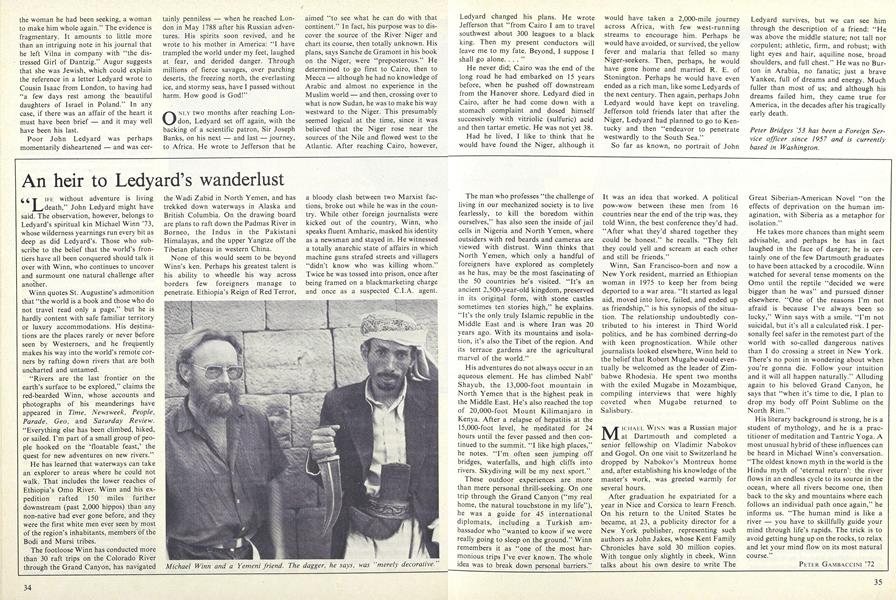

Michael Winn and a Yemeni friend. The dagger, he says, was "merely decorative."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

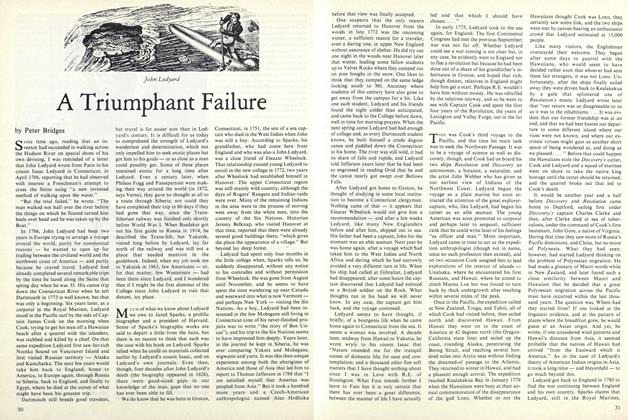

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Peter Gambaccini '72

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE GRADUATE MANAGER'S DREAM

OCTOBER 1931 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for –

JUNE 1978 -

Article

ArticleWhat difference does a Mac make?

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MARCH | APRIL 2016 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MARCH 1973 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE D'38 -

Article

ArticleTHE President of the College has recently returned from an extended

FEBRUARY, 1907 By GEORGE H. HOWARD