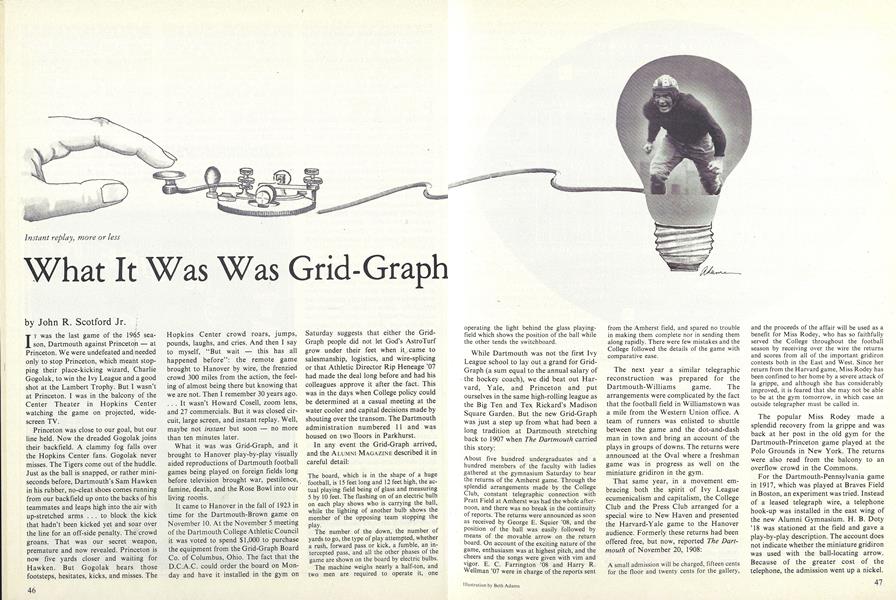

Instant replay, more or less

IT was the last game of the 1965 season, Dartmouth against Princetojn at Princeton. We were undefeated and needed only to stop Princeton, which meant stop- ping their place-kicking wizard, Charlie Gogolak, to win the Ivy League and a good shot at the Lambert Trophy. But I wasn't at Princeton. I was in the balcony of the Center Theater in Hopkins Center watching the game on projected, wide- screen TV.

Princeton was close to our goal, but our line held. Now the dreaded Gogolak joins their backfield. A clammy fog falls over the Hopkins Center fans. Gogolak never misses. The Tigers come out of the huddle. Just as the ball is snapped, or rather miniseconds before, Dartmouth's Sam Hawken in his rubber, no-cleat shoes comes running from our backfield up onto the backs of his teammates and leaps high into the air with up-stretched arms ... to block the kick that hadn't been kicked yet and soar over the line for an off-side penalty. The crowd groans. That was our secret weapon, premature and now revealed. Princeton is now five yards closer and waiting for Hawken. But Gogolak hears those footsteps, hesitates, kicks, and misses. The Hopkins Center crowd roars, jumps, pounds, laughs, and cries. And then I say to myself, "But wait this has all happened before": the remote game brought to Hanover by wire, the frenzied crowd 300 miles from the action, the feeling of almost being there but knowing that we are not. Then I remember 30 years ago. ... It wasn't Howard Cosell, zoom lens, and 27 commercials. But it was closed circuit, large screen, and instant replay. Well, maybe not instant but soon no more than ten minutes later.

What it was was Grid-Graph, and it brought to Hanover play-by-play visually aided reproductions of Dartmouth football games being played on foreign fields long before television brought war, pestilence, famine, death, and the Rose Bowl into our living rooms.

It came to Hanover in the fall of 1923 in time for the Dartmouth-Brown game on November 10. At the November 5 meeting of the Dartmouth College Athletic Council it was voted to spend $1,000 to purchase the equipment from the Grid-Graph Board Cos. of Columbus, Ohio. The fact that the D.C.A.C. could order the board on Monday and have it installed in the gym on Saturday suggests that either the Grid- Graph people did not let God's Astro Turf grow under their feet when it came to salesmanship, logistics, and wire-splicing or that Athletic Director Rip Heneage '07 had made the deal long before and had his colleagues approve it after the fact. This was in the days when College policy could be determined at a casual meeting at the water cooler and capital decisions made by shouting over the transom. The Dartmouth administration numbered 11 and was housed on two 'floors in Parkhurst.

In any event the Grid-Graph arrived, and the ALUMNI MAGAZINE described it in careful detail:

The board, which is in the shape of a huge football, is 15 feet long and 12 feet high, the actual playing field being of glass and measuring 5 by 10 feet. The flashing on of an electric bulb on each play shows who is carrying the ball, while the lighting of another bulb shows the member of the opposing team stopping the Play.

The number of the down, the number of yards to go, the type of play attempted, whether a rush, forward pass or kick, a fumble, an intercepted pass, and all the other phases of the game are shown on the board by electric bulbs.

The machine weighs nearly a half-ton, and two men are required to operate it, one operating the light behind the glass playing- field which shows the position of the ball while the other tends the switchboard.

While Dartmouth was not the first Ivy League school to lay out a grand for Grid- Graph (a sum equal to the annual salary of the hockey coach), we did beat out Harvard, Yale, and Princeton and put ourselves in the same high-rolling league as the Big Ten and Tex Rickard's Madison Square Garden. But the new Grid-Graph was just a step up from what had been a long tradition at Dartmouth stretching back to 1907 when The Dartmouth carried this story:

About five hundred undergraduates and a hundred members of the faculty with ladies gathered at the gymnasium Saturday to hear the returns of the Amherst game. Through the splendid arrangements made by the College Club, constant telegraphic connection with Pratt Field at Amherst was had the whole afternoon, and there was no break in the continuity of reports. The returns were announced as soon as received by George E. Squier '08, and the position of the ball was easily followed by means of the movable arrow on the return board. On account of the exciting nature of the game, enthusiasm was at highest pitch, and the cheers and the songs were given with vim and vigor. E. C. Farrington '08 and Harry R. Wellman '07 were in charge of the reports sent from the Amherst field, and spared no trouble in making them complete nor in sending them along rapidly. There were few mistakes and the College followed the details of the game with comparative ease.

The next year a similar telegraphic reconstruction was prepared for the Dartmouth-Williams game. The arrangements were complicated by the fact that the football field in Williamstown was a mile from the Western Union office. A team of runners was enlisted to shuttle between the game and the dot-and-dash man in town and bring an account of the plays in groups of downs. The returns were announced at the Oval where a freshman game was in progress as well on the miniature gridiron in the gym.

That same year, in a movement embracing both the spirit of Ivy League ecumenicalism and capitalism, the College Club and the Press Club arranged for a special wire to New Haven and presented the Harvard-Yale game to the Hanover audience. Formerly these returns had been offered free, but now, reported The Dartmouth of November 20, 1908:

A small admission will be charged, fifteen cents for the floor and twenty cents for the gallery, and the proceeds of the affair will be used as a benefit for Miss Rodey, who has so faithfully served the College throughout the football season by receiving over the wire the returns and scores from all of the important gridiron contests both in the East and West. Since her return from the Harvard game, Miss Rodey has been confined to her home by a severe attack of la grippe, and although she has considerably improved, it is feared that she may not be able to be at the gym tomorrow, in which case an outside telegrapher must be called in.

The popular Miss Rodey made a splendid recovery from la grippe and was back at her post in the old gym for the Dartmouth-Princeton game played at the Polo Grounds in New York. The returns were also read from the balcony to an overflow crowd in the Commons.

For the Dartmouth-Pennsylvania game in 1917, which was played at Braves Field in Boston, an experiment was tried. Instead of a leased telegraph wire, a telephone hook-up was installed in the east wing of the new Alumni Gymnasium. H. B. Doty '18 was stationed at the field and gave a play-by-play description. The account does not indicate whether the miniature gridiron was used with the ball-locating arrow. Because of the greater cost of the telephone, the admission went up a nickel. However, the sponsors went back to telegraphic transmission until the Dartmouth-Cornell game of 1922, when radio was first used. The Dartmouth reported:

Radio broadcasting from the Polo Grounds, New York City, giving play by play reports of the Cornell game may be arranged by the Radio Club. The recently acquired set, presented to the club by Charles G. Du Bois '91, makes this a possibility. If the proposed plans are satisfactory, the set will probably be capable of not only amplifying the reports of the Polo Grounds game, play by play, but will allow the audience to hear the playing of the band and the cheering of the spectators.

Mr. W. A. Heppner of the Western Electric Company, who supervised the installation of the new set, gave an interesting talk at the meeting of the club held last night in 104 Wilder. Mr. Heppner pointed out the details and explained the workings of the set, and also . . . stated that the science is still in its infancy, and there is a great field for development.

The next year the sophisticated, big time, Grid-Graph board arrived. In addition to the non-home Dartmouth contests, it was used for the Harvard-Yale game at 50 cents a head.

One of the Hanover notables most closely associated with the running of the Grid-Graph for the 18 years it entertained the Saturday afternoon stay-at-homes was Bert Sargent, chief engineer of the College heating plant. When he recalls the back-of- the-board excitement during the big games, the scene comes alive. "Larry Love, who ran the Western Union Office downtown; would set up his receiving equipment in one of the handball courts just off the baseball cage in the East Wing," Sargent said recently. "The wooden stands were set up in a semi-circle in front of the Grid-Graph board and would start filling up a half hour before game time. A lot of townspeople would join the students, and it was the crowd and the noise that made it so much fun. Not all Dartmouth games were broad cast in those days, and, besides, student couldn't have radios in the dorms.* Buster Brown, one of the College painters, would lead the cheers and songs since the varsity cheerleaders were away at the games. The Saia brothers had their hawkers in the stands selling hot dogs and Coke. It was just like a real game but out of the rain.

Even the Hanover dog pack was there and the faculty kids roaming around scavenging under the stands.

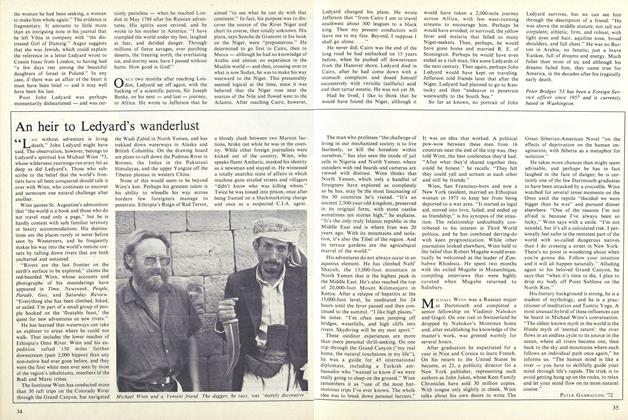

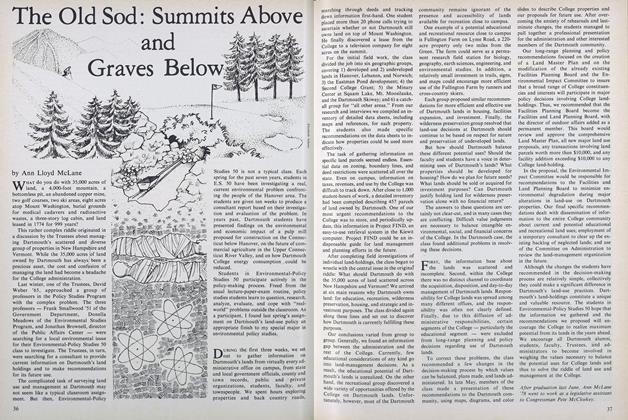

"When the game began Larry would start transcribing the dots and dashes coming over the wire onto the regulation Western Union yellow telegraph forms. One play for each sheet. He handed these through the slot in the wall to me. I would read the play over to myself and then reduce it to instructions for our crew. Behind the board were three sets of switches. One set of eleven for the Dartmouth team on one side, another of eleven for the opponents on the other. In the middle was a set of switches for the type of play and the result (see diagram). I might say, 'Okay, 73 snaps to 15 hands off to 28 thru the line for 15 yards tackled by Harvard 40 and 55.' The men would lower the switches I had called halfway. When they were all cocked, Dave Rennie, our chief-of- staff, would say 'All set, let's run it.' He would push down 73 and the light for Gibson would come on. Then Phil Trachier who impersonated the ball with a light on the end if a long cord would slide his cup of light held against the translucent gridiron back from the 25 yard marker to the 20. Then Dave would light number 15 Gates and then 28 Hollingworth. Phil would run the light/ball back to the line. Dave would point to Austin Cook, who would hit the through-the-line switch. Phil would wiggle the light/ball while the crowd held its breath. Then he'd do some broken field dancing down to the 40 when Paul Wormwood would hit the switches indicating that Harvard's 40 Oakes and 55 Macdonald had made the stop. Dave, Austin, and Paul worked at the bank and they made a great team.

"Of course, over the years the Grid- Graph crew would change from time to time. We used a lot of medical students. They had all been in Hanover five or six years and knew the players' names and positions and the plays. And they needed the money.

"Grid-Graph was part of my regular job. Originally, I was just assigned to be there if something broke down, but as I became familiar with the set-up and with Dartmouth football I took over breaking down the plays as they came through the slot from Larry and alerting the switchers."

Sargent's most vivid recollection is the 1931 Dartmouth-Yale 33-33 tie. "That's the time I thought the stands would collapse and the board be blown away," he said. "The Yale jinx was still working. We had never beaten them. It was the Big Game. They had Albie Booth, we had Air Mail Morton and Wild Bill McCall. We were down 26-10 at the half and 33-10 in the third quarter. It was a gloomy, quiet crowd out there. Then the team and the game and the crowd went wild. McCall took the kickoff after the last Yale touchdown for 94 yards to make it 33-16. After we kicked off we held them, blocked their punt, and scored again. Now 33-23. The crowd was standing and screaming, and we were flipping switches and sweating. McCall intercepted a pass intended for Booth and ran that in from 60 yards away: 33-30. Air Mail Morton lived up to his name and got us down to the 10 on passes. Then Yale stopped us in the line and in the air. We lost four yards and were on the 14. It was third down but only time for one more play. The Grid-Graph crew was as tense as the players, I am sure. We had to get it right and do it fast because it was happening fast. The fans out there were jumping up and down and those old wooden bleachers were creaking and shaking. Morton dropped back to the 24-yard line. McCall took the snap and put the ball on the grass. Morton kicked it 34 yards through the goal posts and the game was over, 33-33. The Grid-Graph crew was exhausted physically, mentally, and emotionally, but there was no lying down and saying 'phew.' That crowd came out of those swaying stands and across the floor bent on getting some souveniers of the game from the board. We had to rush out in front and fend them off or the whole thing would have caved in on us all. They tore out the players' names and got a few lights, but we saved the board."

One of the med students who earned five dollars a game behind the Grid-Graph board was Jackson Wright '33. He thinks it was Dean Syvertsen who promoted the medical students' virtual monopoly as crew members. They had Saturday classes until noon and were allowed no cuts, so they weren't leaving town. He also has colorful memories of the 33-33 tie game. "My classmate Al Ball was, appropriately enough, handling the light that indicated the football," Wright said. "It used to get hot so we wound it with friction tape so A1 could hang on to it. Of course, if the bulb burned out, we had to unwind all that tape to install a new one. We learned to put a new bulb in before the game began. A1 was something of a ham; as the 1931 Yale game got better and better he would sustain the suspense by slowing down the passes and taking a few extra zig and zags on the runs. As the game drew to its climax we were about eight plays behind. We knew the out- come but wanted to give our audience a good show, so we took our time and added a few artistic flourishes. Unfortunately, somebody from one of the fraternity houses that had a radio came in to the gym and announced the outcome before we had finished. Bert Sargent says they were after souvenirs when they came boiling out of the stands. I have always thought they were enraged at our delay and creative play- running. A1 and I saw them coming and bolted out the back door."

The Dartmouth always had a love-hate relationship with the rival news medium over the years, calling it "the famed dummy game" and accusing its operators of substituting speed for accuracy or vice versa, depending upon whether the goofs or delays were more apparent at the last performance. During the 1938 season the paper commented:

We like especially the little familiarities indulged in by members of the working crew. Three years ago, for example, the audience sat on the edge of its collective seat, while the Big Green made a goal-line stand to hold Princeton from scoring in the snowstorm. After a particularly spectacular play, a megaphone was thrust out from behind the battery of lights, and a voice announced calmly that a drunk had "run out of the stands and tackled Sandbach."

Things are quite orderly for a certain length of time until the substitutions, penalties, and forward passes throw the men at the switches into a panic of confusion, at which time there are some remarkable things accomplished by the team. Our versatility was admirably proven in the Cornell game two years ago, the last time we played in Ithaca, when the best linebacker in the East, Johnny Handrahan, was dis- tinguishing himself with superb end runs, and Bob MacLeod bucked the line for long gains. According to one slightly biased report, by the fourth quarter the guards were catching shovel passes thrown by an unbalanced end, while a mysterious halfback named Joe booted an 11- yard punt offside on our 23-yard line.

But they always beat the drum for a crowd, and when Grid-Graph died or was the victim of euthanasia in 1941, the paper's obituary was chin-up but not dryeyed:

To those of you members of the class of 1945 who are well enough acquainted with the Hanover scene, let it be said that the Grid- Graph is no more that will suffice. But to the far greater number who have never heard tell of the Grid-Graph, let us say that it was a type of wondrous mechanism that (more or less) brought the action of varsity football games played away from home virtually to the dirt floor of the Alumni Gym.

The wizardry of this forerunner of television was simple. Ticker tape, a translucent board lined like a football field, and a moving light approximately following the play of the game did the trick. The reason given by the D.C.A.C. for the discontinuance of this delightful custom was the dwindling attendance of recent years and the resultant lack of chink in the clink.

Follow the lights (white dots) in this Sargent-Scotford recollection of the Grid-Graph board: fourth period, third down and three yards to go, Dartmouth ball;Hollingworth plunges 15 yards to the 40, stopped by Harvard's Oakes and Mac Donald.

*The college power produced in the heating plant was direct current then, not AC. No bulbs larger than 25 watts were allowed, and hot plates, radios, and other appliances were banned. It was not just stinginess on the part of the College, it was also dangerous. Students could have battery-operated radios, but some Thayer School students, to save money and a trip to a gas station to have their battery recharged, cobbled together homemade chargers. Often these would blow the fuse. But even with a fuse blown, according to Bert Sargent, the DC current could arc and melt down the offending appliance. Sargent says he replaced 2,500 fuses a year. He would while away the slack hours in the heating plant resoldering those 2,500 fuses.

John Scotford '38, whose last article in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE was " 'Unquestion-ably the ugliest building in Hanover"(about Moor-Chandler Hall), is a graphicdesigner who served the College in that rolefor 24 years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleAn Heir to Ledyard's Wanderlust

October 1980 By Peter Gambaccini '72

John R. Scotford Jr.

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

April 1954 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

April 1956 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

April 1957 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

MAY 1957 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

June 1957 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938

May 1958 By JOHN H. EMERSON, JOHN R. SCOTFORD JR.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSerenity Now

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 -

Feature

FeatureThe Old Sod: Summits Above and Graves Below

JAN./FEB. 1979 By Ann Lloyd McLane -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Cover Story

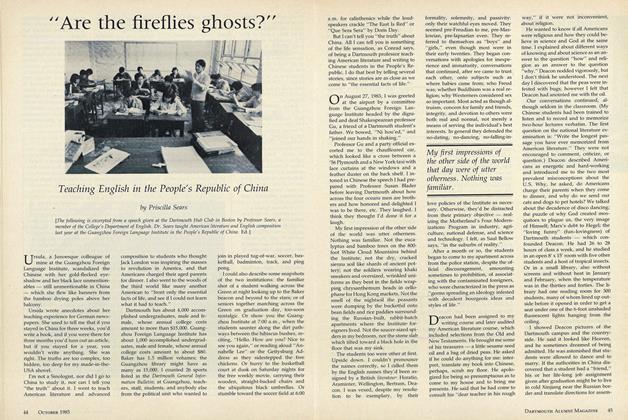

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

OCTOBER 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Feature

FeatureCreativity: The Open Dance at Dartmouth

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Prof. Blanche Gelfant -

Feature

FeatureBeauty and the Beasts

October 1978 By William Morgan