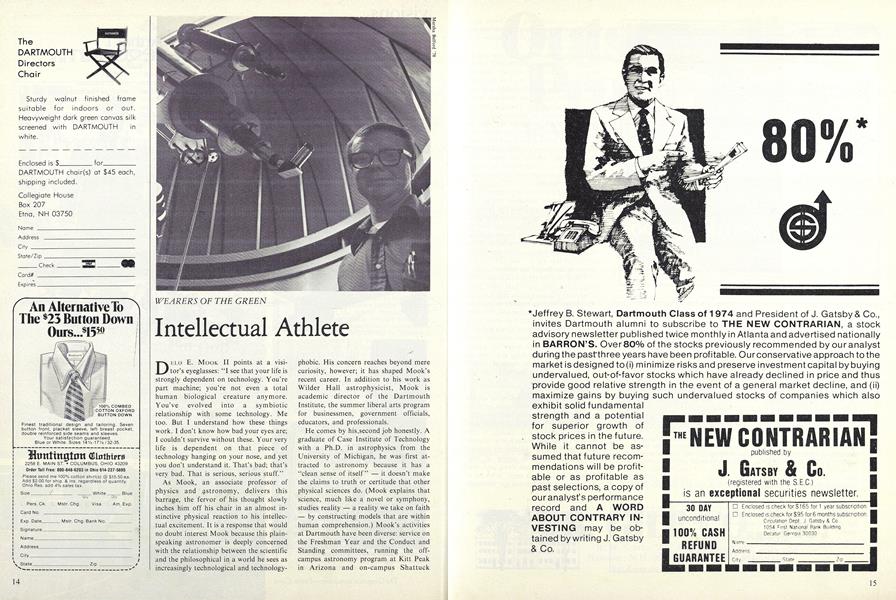

DELO E. MOOK II points at a visitor's eyeglasses: "I see that your life is strongly dependent on technology. You're part machine; you're not even a total human biological creature anymore. You've evolved into a symbiotic relationship with some technology. Me too. But I understand how these things work. I don't know how bad your eyes are; I couldn't survive without these. Your very life is dependent on that piece of technology hanging on your nose, and yet you don't understand it. That's bad; that's very bad. That is serious, serious stuff."

As Mook, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, delivers this barrage, the fervor of his thought slowly inches him off his chair in an almost in- stinctive physical reaction to his intellec- tual excitement. It is a response that would no doubt interest Mook because this plainspeaking astronomer is deeply concerned with the relationship between the scientific and the philosophical in a world he sees as increasingly technological and technology phobic. His concern reaches beyond mere curiosity, however; it has shaped Mook's recent career. In addition to his work as Wilder Hall astrophysicist, Mook is academic director of the Dartmouth Institute, the summer liberal arts program for businessmen, government officials, educators, and professionals.

He comes by his.second job honestly. A graduate of Case Institute of Technology with a Ph.D. in astrophysics from the University of Michigan, he was first attracted to astronomy because it has a "clean sense of itself" — it doesn't make the claims to truth or certitude that other physical sciences do. (Mook explains that science, much like a novel or symphony, studies reality — a reality we take on faithby constructing models that are within human comprehension.) Mook's activities at Dartmouth have been diverse: service on the Freshman Year and the Conduct and Standing committees, running the off- campus astronomy program at Kitt Peak in Arizona and on-campus Shattuck Observatory, overseeing the Choate dormitories, and, revealingly, discoursing on Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow at a faculty seminar.

In short, Mook displays an extraordinary "intellectual athleticism," according to Professor of English Thomas Vargish, who preceded Mook at the Dartmouth Institute, which makes him especially fit to manage the institute's inter- disciplinary curriculum. Admitting that the scientific approach is but one way to see the world, Mook recognizes the need to make connections between the topics discussedin his science course and the issues raised in the institute's "values and ethics" and "America" courses. He believes that decision-makers, and people at large, should be able to view problems from more than one perspective:

"I don't care who you are, whenever you finish your formal education and get out into the world, you get into a rut. That's as much true with a professor as with anyone else. One of the very difficult things to do is to lift yourself out of that rut of thinking. Most people cannot do it themselves. What we provide is an opportunity to help people get out of that rut ... and take a look around at the rest of the terrain.

"I think what we try to do is to say to the participants: 'We don't care what your beliefs are. We don't really care how you view things. What we're going to try to do is let you see things another way. Whether you choose to accept that view or not is up to you. But whatever your beliefs are, we'd like to show you that there are other ways of looking at the same thing. Two people can look at the same thing and come up with radically different views of reality. And it's not a case of one being right and one being wrong — they're just different.' "

Mook feels that this shaking up applies to the institute's faculty who must at- tend all the classes and do all of the exten- sive reading as well as the other par- ticipants. He finds that teaching in this holistic atmosphere makes him a "sharper and a better teacher" whether the students are undergraduates or people in midcareer. "For me to sit down and read Freud or Zola," Mook says, "is for me to do something that I would not ordinarily do. For Steve Nichols [professor of French] to confront me with the nature of modern art or for Ron Green [associate professor of religion] to confront me with the problem of a just God in the face of human suffering gets my mind working in ways that it ordinarily doesn't." Indeed, interdisciplinary studies, Mook says, deserve a more widespread application on the undergraduate level because they give both teacher and student a grander view of their limited role in the events of the universe.

These sentiments sound suspiciously territorial coming from an astronomer, whose colleagues often tend to monopolize any musings on cosmology. But Mook, who gets an earful of more earthly world views from his associates at the institute, claims not to be especially interested in astronomy's "who are we, where are we" aspect. Rather, his specialization, celestial x-ray sources, is usually comprised of long hours at the telescope (a television screen more commonly), locating and then observing binary star systems. These systems, because of the exchange of mass between the stars, emit x-rays, and offer the best opportunity to study black holes. Now that this field is beginning to be understood that is, acceptable models have been outlined Mook is eyeing a new, less widely researched corner of the sky: huge star masses whose optical outputs vary on short time scales.

Of all this esoterica, however, Mook speaks routinely. While astronomy remains his bread and butter and still interests him greatly, Mook seems to be more intense when discussing broader subjects. Vargish suggests, "Mook is a humanist as well as a scientist."

According to Mook, the shift in research specialization that he is contemplating is typical of the way in which academics expand their horizons: They tend to add new knowledge to knowledge already acquired rather than substitute knowledge for ignorance. Mook suggests that all faculty should have the Opportunity to transcend their self-imposed limitations with an institute-like post. "I find," he says, "that I keep sharp as a teacher when I'm a student in a classroom listening, reading, coming, to grips with material which I would never have thought of looking at before, wrestling with ideas which are complicated, listening to somebody and not completely understanding what the deuce he's saying just the way undergraduates do. I've found it so important for me to remember what it is not to understand something. That sounds trite, except that you do sometimes lose sight of that."

When he gets excited, Mook smacks somewhat of the boyish idealist. Not only has he hinted that faculty should be required to serve time as students in a classroom, but he also, unsuccessfully, supported an undergraduate calculus requirement parallel to the one presently in effect for English. Dartmouth students are no different from a large percentage of the general population, Mook argues, in their aversion to and fear of science. "Students can graduate from Dartmouth and not only not know centuries-old mathematics that was part of the Enlightenment, they can graduate and not understand how their bodies are put together or how the universe is put together basic things that humans have been struggling to come to grips with for centuries. We don't require a fundamental understanding of anything," he says, evincing a faith in his belief that we cannot begin to understand reality if we nore entire areas of knowledge.

This ignorance leads to a feeling of helplessness and alienation in the face of a world growing more technological each day, Mook continues. Despite post- Copernican efforts to shield ourselves from the unsettling effects of scientific discoveries, recent hypotheses should they prove true could once again threaten our theological, ethical, and physical beliefs. Mook concludes, "People care where and who they are and when you shake a foundation of our Self-perception, it's a profoundly disturbing event.. . . One of the great sadnesses that 1 have for our society, and it's really why I do what I do, is that most people don't understand about science."

If Mook attacks these problems with the vigor that led him to monitor a single light source for 42 straight nights, only to climb another mountain the next night to help a fellow astronomer with another project, then the boundaries between the sciences and the humanities at Dartmouth will need strength enough to withstand a modern deluge. For Dee Mook, as friends call him, is a scholar of rare energy in a community where diversity and intensity of scholarship do not necessarily walk hand in hand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleAn Heir to Ledyard's Wanderlust

October 1980 By Peter Gambaccini '72

Don Rosenthal '81

-

Article

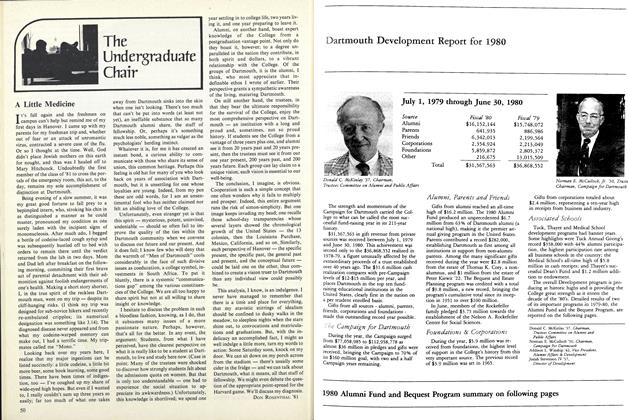

ArticleA Little Medicine

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleBeware the Shrimp

Jan/Feb 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleWhere They Live

April 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleMind for Adventure

May 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Article

ArticleA Straight Talk

June 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81