From the bustle to the bosom and the bottom

CONSIDHR what it would be like to wear a chemise, corset, corset-cover, stockings, two petticoats, starched linen blouse, long skirt, high heels, and a straw hat. .. to play tennis. Before you smile too smugly, know that this outfit was an absolute must for the athletic Victorian lady. As you relax wearing your blue jeans, T- shirt, and Adidas, may 1 suggest that you count your blessings. It wasn't always this way!

It does not matter that the sewing machine wasn't in common use until the 1850s or that the zipper wasn't invented until the 1920s; for centuries "civilized" people have been quick to follow the suddenly shifting tides of style, adorning themselves in seemingly ludicrous attire, pinching, distorting, and exaggerating the human figure in the name of fashion. Throughout history, however, the whimsies and vagaries of human dress have been recorded with a minimum of fact and a generous supply of fantasy. Not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries did the serious and scholarly study of clothing begin accurately to illustrate how our ancestors dressed and why.

Together with the development of serious costume scholarship came a growing interest in the collection and exhibition of clothing, particularly in Europe. In America, the interest has been more recent. For instance, the internationally known collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute in New York was founded in 1937. Organized independently of the Metropolitan by the Lewisohn sisters and stage designers Aline Bernstein and Lee Simonson, the collection did not become an incorporated, curatorial department of the museum until 1959.

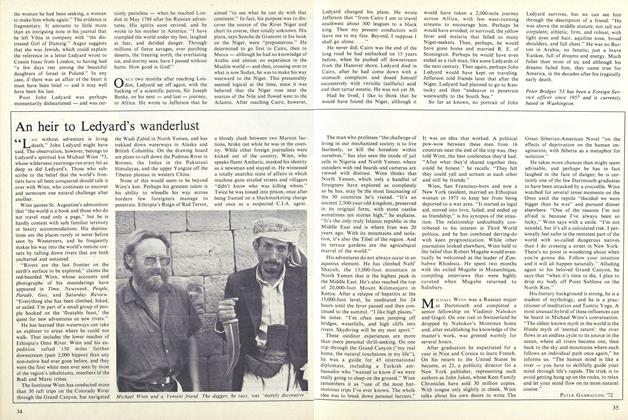

At the time the founders of the Costume Institute were discussing how to establish their collection in New York City, a young man from Philadelphia named Henry Williams was completing his studies in directing and stage design at the Yale School of Drama. In 1931, Henry Williams came to Dartmouth as technical director, and eventually stage director and designer, for the Dartmouth Players. Realizing the value in having authentic research material for the design and construction of The Players' costumes, Williams began soliciting antique clothes from Hanover-area residents. Marvelous period costumes began appearing at his office door, and, in. 1934, the Dartmouth Players costume collection was founded. In its 46-year history, the collection has grown to comprise over 2,000 items of men's, women's, and children's clothing spanning three centuries including such Dartmouth treasures as Eleazar Wheelock's academic robe and President Hopkins' freshman beanie.

Last December, in recognition of the current interest in historic costume, the Dartmouth College Museum and Galleries presented an elegant, nostalgic look at women's fashions from the Williams Collection. The exhibition, titled "Women's Clothing and Accessories: 1800-1930," offered the Hanover audiences a glimpse into a time when New England women wore tight corsets and exaggerated hoops, professors' wives danced the night away in galmorous beaded dresses, and Hanover ladies outdid themselves in graceful Paris ballgowns a far cry from the down jackets and snow- boots worn to the exhibition.

I know it is difficult to imagine how those same down jackets or snowboots could ever be of interest to a museum costume collection, but today's L. L. Bean will be tomorrow's cultural heirloom. For instance, those tired old jogging shorts that countless Americans put on each morning are an important expression of contem- porary lifestyles and current cultural values. The American attitude toward the human body has changed so drastically during this century that yesterday's Victorian tennis player would undoubtedly succumb to a maidenly faint at the sight of today's female jogger. We have come a long way considering that with advent of short skirts in the 1920s, women's legs were on public view in polite society for the first time since the Greeks.

While jogging shorts and blue jeans reflect today's values, it is the glamorous and expensive clothes of haute couture that truly qualify as works of art. For centuries, tailors and dressmakers, however brilliant, were virtually unknown to the public. It was the kings and courtiers they dressed who set the styles, influenced fashion, and took all the credit. During the 18th century, a French dressmaker named Rose Bertin changed that anonymity by inventing haute couture as we know it today. Bertin's success as dressmaker to Queen Marie Antoinette established her reputation as the most sought-after designer and dressmaker in the court circles of Paris and London. Despite Bertin's success, the idea of haute couture was slow in developing. Nearly a century later, an Englishman, Charles Frederick Worth, opened an exclusive dress salon in Paris, capturing the attention of the beautiful and fashionable Empress Eugenie. Through the publicity gained from her patronage, Worth designed the wardrobes, trousseaus, and presentation dresses for the wealthiest and most beautiful women in the world. In fact, the House of Worth was an important and necessary stop for rich American mamas husband-hunting on the continent for their marketable and marriageable daughters. As a result, many American museums are blessed with Worth originals.

Following Worth came a succession of great 20th-century couture designers: Fortuny, Vionnet, Chanel, and Dior, to name a few. It was Fortuny who dressed the great Isadora Duncan in "Grecian" gowns when she threw away her corsets; Vionnet perfected the slinky bias-cut dress which became the rage in Hollywood during the 1930s; Chanel, of course, invented her famous suit and made costume jewelry terribly chic; and Dior's "New Look" in 1947 created a glamorous and feminine image for women during the post-war years. Through their sensitivity to the color and texture of the cloth, the line and composition of the pattern shape, as well as the craftsmanship of the construction, these 20th-century couture designers were able to create garments of innovative style and lasting beauty.

Enough about the past, what about the future? Where do we go from here in this crazy world of ever-changing fashions?

James Laver, the renowned British costume historian, espouses a theory he believes explains the fashions of the past and that might predict the fashions of the future. It is provocatively called the Theory of the Shifting Erogenous Zone. Very briefly, he believes that in each historical period, a specific area of the human anatomy is singled out as having the most "erotic capital." This area, or erogenous zone, is given fashionable focus through clothing of the times, by either uncovering the area (short skirts in the 1920s), exaggerating its size (the bustle in the 1880s), or by draping fabric tightly around it (today's designer jeans). Eventually, the zone loses its impact, becomes boring, and looks old hat. Then the focus changes, and a new erogenous zone becomes the avant- garde trend.

During the 80 years of this century, the erogenous zone has shifted from the hour- glass figure in 1900 to legs in the twenties, bare backs in the thirties, padded shoulders in the forties, tiny waists in the fifties, thighs in the-sixties, to the bosom and the bottom in the seventies. What about the 1980s? The erotic capital of the past few decades seems to have been temporarily exhausted, and the wholesome, classic, collegiate, and "preppy" looks are in. It's tweeds and sweaters, folks! You and I know that the places of higher education in this country have never been singled out for their sartorial splendor, but Seventh Avenue is doing its best to make us believe otherwise.

Don't give up hope! Fashion never stands still, and prudery never stays in style for very long. So, for those of you who long for the more glamorous and risque days, take heart. An old adage in the world of costume history says that hemlines always follow the stock market. If you can predict the future of the stock market, why not try the world of fashion? You might make a killing!

1. Wedding dress of off-white silk, lace applique, chiffon, andpearls. Made in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1903, the dress wasworn by the mother of Sarah Emily Schoenhut, who was costumedesigner for the 1962 Hopkins Center season and whose husbandwas professor of drama and scene designer from 1942 to 1969.

2. Hand-painted paper fan, "The Fencing Lesson," European,ca. 1890-1910.

3. Day dress, from Worcester, Massachusetts, ca. 1800-1820.Made from gray silk saved from an 18th-century dress, this dress,probably homemade, was worn and altered over a 20-year period.

4. Day dress, from Boston, ca. 1855-60. Of blue and brown plaidsilk, this dress, also probably homemade, was altered as the stylesof the 1850s changed at the beginning of the next decade.

5. Afternoon dress, from Vienna, Austria, ca. 1873-75. Made ofcharcoal gray and light gray silk.

6. Dinner dress, possibly Philadelphiaorigin, ca. 1884-89. Made of lavender silk,patterned silk velvet, and beige machinemade lace.

7. Ballgown made by Weeks of Paris, ca.1908-09. Worn by Marianne Faulkner,who was instrumental in the creation andsubsequent development of FaulknerHouse at Mary Hitchcock MemorialHospital. The Faulkner Recital Hall inHopkins Center was given in her memory.

8. Day dress, New England origin, ca.1925-26. Made of yellow, brown, andorange silk. This dress was worn by Mrs.Russell Kilborne, an interior decorator inHanover, whose husband was professor ofbanking and finance at Tuck School.

9. Evening dress, American, ca. 1925.Made of black chiffon, beaded in a blackand silver Art Deco design (detail above).

Margaret Spicer is assistant professor ofdrama, costumer designer, and curator ofthe costume collection at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

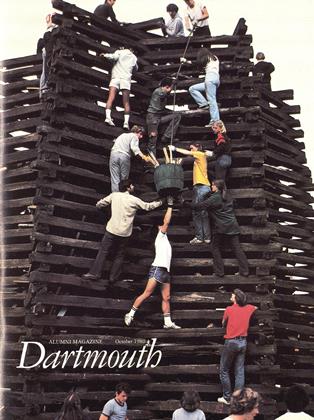

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT -

Article

ArticleAn Heir to Ledyard's Wanderlust

October 1980 By Peter Gambaccini '72

Features

-

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

December 1987 -

Feature

FeatureThe Diminishing Citizen

July 1962 By BASIL O'CONNOR '12 -

Feature

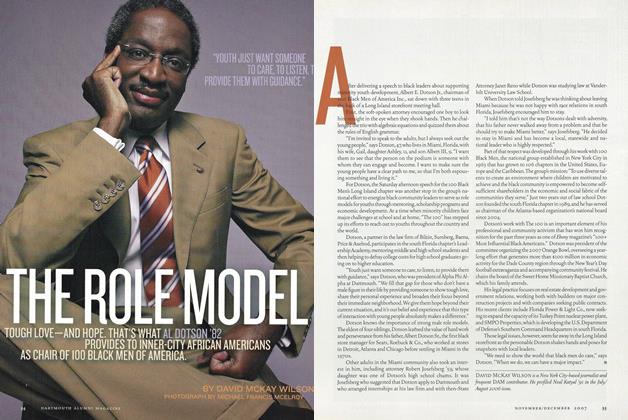

FeatureThe Role Model

Nov/Dec 2007 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

FEATURES

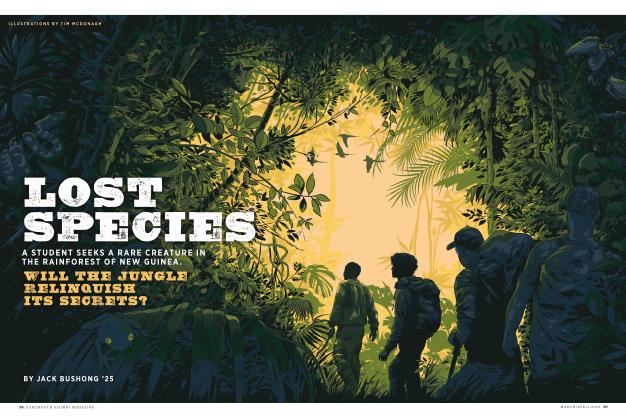

FEATURESLost Species

APRIL 2025 By JACK BUSHONG ’25 -

Feature

FeatureGood Teaching: A Case Study

February 1956 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

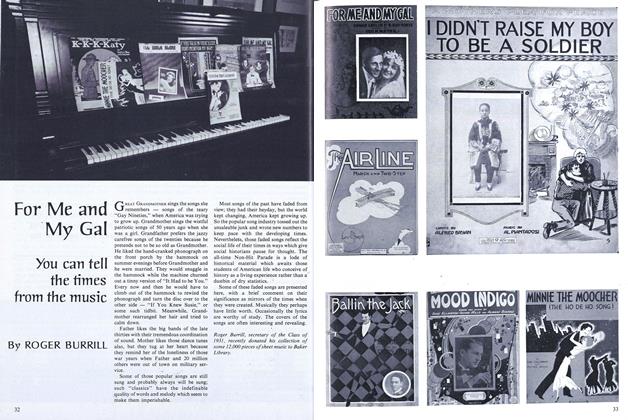

FeatureFor Me and My Gal

October 1976 By ROGER BURRILL