While Bob Thebodo has been climbing trees and trying to kill beetles, W. Charles Kerfoot, an assistant professor of biology, has been wading in Occom Pond, trying to cultivate a population of water fleas more properly known as daphnia micro- crustaceans that feed on algae. The purpose of the experiment, funded in part by the National Science Foundation, is to develop biological methods to control "nuisance algae," of which Occom Pond has an abundance. If the project works, Kerfoot said during a recent conversation, "it will open up the possibility that just as there is management of terrestrial systems, these zooplankton might be able to help us manage problems in aquatic systems." Occom Pond's problem with algae most likely stems from a long history of fertilizer run- off, rich in phosphates and nitrates, from adjacent property, including the golf course. In effect, the thriving, oxygen- consuming algae are choking the life out of the pond. The murky water smells; the only fish it supports are bullheads and goldfish.

This summer, in the first two stages of his experiment, Kerfoot used plastic bottles anchored in the pond, then larger enclosures or "corrals," to isolate the daphnia (obtained from a nearby lake) from predatory fish and to establish the various species' ability to multiply and consume algae. When we talked with Kerfoot this fall he was about to begin the third stage "seeding the entire pond with daphnia" and, at the same time, removing the pond's fish population to permit the daphnia to multiply unchecked. The fish were to be removed by "chumming" and netting, charging the water with electricity, and trapping. (Ways of disposing of the fish using them for fertilizer, for example were being investigated.)

One of the nice things about daphnia, which are often sold as goldfish food, Kerfoot explained, is that their eggs resemble little seeds and can withstand long periods of desiccation and are therefore easy to transport from one pond and "sow" in another. He is aiming to achieve a high population of daphnia in Occom and, fortunately, because of their exponential rate of population growth under good conditions, a relatively few daphnia introduced at first will multiply rapidly. One daphnia per liter of pond water will begin to have an effect on the algae, Kerfoot pointed out, 20 daphnia per liter will start to regulate the amount of algae, and 50 daphnia per liter will "knock down anything." That's the sort of concentrated population that the algae of Occom Pond will be up against.

Using rough figures, Kerfoot ran through a few quick calculations to give us a more detailed idea of what the project involves. The pond is about 180 feet wide and 1,120 feet long, he said, and it has an average depth of about four feet. That means it contains approximately 806,400 cubic feet or 22,837 cubic meters of water. One cubic meter contains 1,000 liters, he reminded us, and with a concentration of 50 daphnia per liter, a cubic meter of Occom Pond water would contain some 50,000 daphnia. The entire pond would have something on the order of 23 million daphnia, all busy chomping on algae. Their propensity to "graze down algae," Kerfoot noted, has given them the nickname "cattle of the water." A herd that large won't be a problem in itself, he reassured us. The daphnia won't even be noticed; only their impact on the algae will be evident and their numbers depend on the available food supply.

He said he expects a noticeable improvement in the water quality by next June. The whole experiment is a "pioneering attempt," he added, and if it works "it will be an important breakthrough." Kerfoot already has some good evidence that the experiment is progressing as it should. In one of the enclosures containing daphnia, observers were able to look down and see the previously hidden bottom of the pond. Peering down into the water they spotted a golf ball.

Dartmouth Hall loses another shading elm.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Article

-

Article

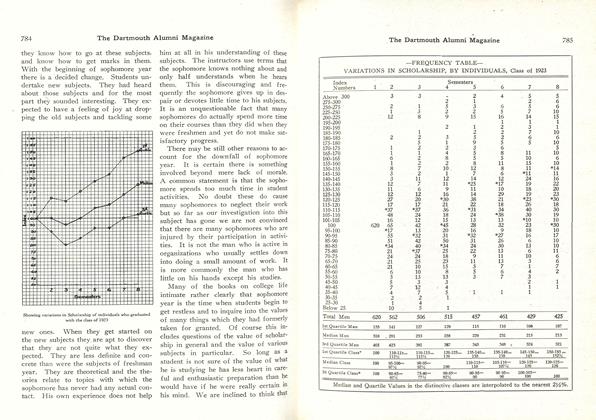

ArticleFREQUENCY TABLE VARIATIONS IN SCHOLARSHIP, BY INDIVIDUALS, Class of 1923

August 1924 -

Article

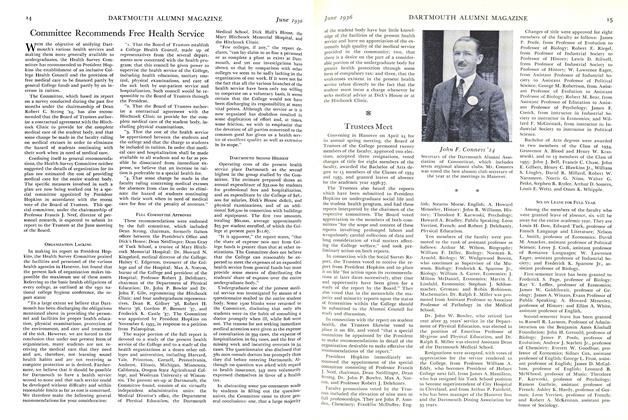

ArticleCommittee Recommends Free Health Service

June 1936 -

Article

ArticleCircling the Green

NOV. 1977 -

Article

ArticleSpecial Train System

June 1929 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleWOODSMEN

January 1933 By J.S. M. '33 -

Article

ArticleCLASS OF 1908

June 1916 By Laurence M. Symmes