Wherever they may have been on this girdled earth, members of the Dartmouth community experienced a common pride with the good news that George D. Snell '26 had been awarded perhaps the world's most cherished honor, a Nobel Prize.

Described by those who know as "the world's leading authority on the genetics of transplant reactions," Snell shares the 1980 prize for medicine with two scientists in kindred areas, a Frenchman and an American of Venezuelan birth. In the words of the citation, he has "helped to deepen the understanding of cell interaction and enabled the field of tissue transplantation to grow."

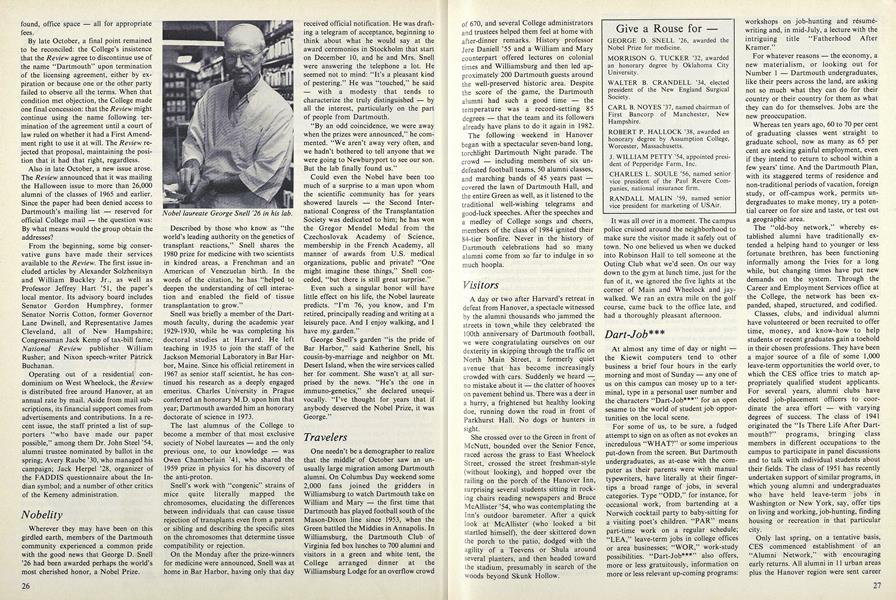

Snell was briefly a member of the Dartmouth faculty, during the academic year 1929-1930, while he was completing his doctoral studies at Harvard. He left teaching in 1935 to join the staff of the Jackson Memorial Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine. Since his official retirement in 1967 as senior staff scientist, he has continued his research as a deeply engaged emeritus. Charles University in Prague conferred an honorary M.D. upon him that year; Dartmouth awarded him an honorary doctorate of science in 1973.

The last alumnus of the College to become a member of that most exclusive society of Nobel laureates and the only previous one, to our knowledge was Owen Chamberlain '4l, who shared the 1959 prize in physics for his discovery of the anti-proton.

Snell's work with "congenic" strains of mice quite literally mapped the chromosomes, elucidating the differences between individuals that can cause tissue rejection of transplants even from a parent or sibling and describing the specific sites on the chromosomes that determine tissue compatibility or rejection.

On the Monday after the prize-winners for medicine were announced, Snell was at home in Bar Harbor, having only that day received official notification. He was drafting a telegram of acceptance, beginning to think about what he would say at the award ceremonies in Stockholm that start on December 10, and he and Mrs. Snell were answering the telephone a lot. He seemed not to mind: "It's a pleasant kind of pestering." He was "touched," he said - with a modesty that tends to characterize the truly distinguished by all the interest, particularly on the part of people from Dartmouth.

"By an odd coincidence, we were away when the prizes were announced," he commented. "We aren't away very often, and we hadn't bothered to tell anyone that we were going to Newburyport to see our son. But the lab finally found us."

Could even the Nobel have been too much of a surprise to a man upon whom the scientific community has for years showered laurels the Second International Congress of the Transplantation Society was dedicated to him; he has won the Gregor Mendel Medal from the Czechoslovak Academy of Science, membership in the French Academy, all manner of awards from U.S. medical organizations, public and private? "One might imagine these things," Snell conceded, "but there is still great surprise."

Even such a singular honor will have little effect on his life, the Nobel laureate predicts. "I'm 76, you know, and I'm retired, principally reading and writing at a leisurely pace. And I enjoy walking, and I have my garden."

George Snell's garden "is the pride of Bar Harbor," said Katherine Snell, his cousin-by-marriage and neighbor on Mt. Desert Island, when the wire services called her for comment. She wasn't at all surprised by the news. "He's the one in immuno-genetics," she declared unequivocally. "I've thought for years that if anybody deserved the Nobel Prize, it was George."

Nobel laureate George Snell '26 in his lab.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

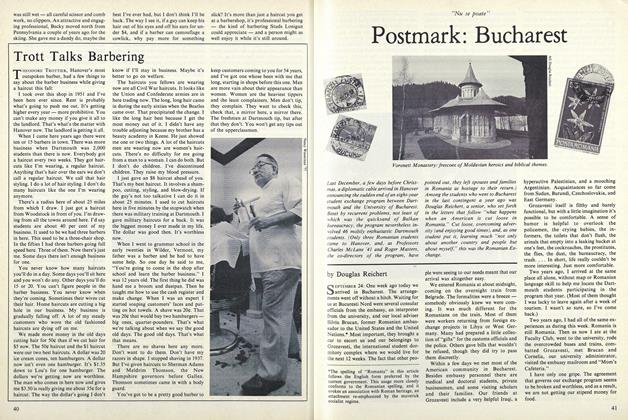

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66

Article

-

Article

ArticleGENERAL STREETER'S WORK IN THE AMERICANIZATION MOVEMENT

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleThe Schedule

February, 1923 -

Article

Article1927 Presents 2 5-Year Gift

July 1952 -

Article

ArticleBook Awards Program Brings College to High Schools

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 -

Article

ArticleSports Schedule

January 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleBig Tuck

May 1994 By Robert H. Nutt '49