THE WHITE LANTERN

by Evan Cornell '45 Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 279 pp. $11.95

The White Lantern is a sequel to A Long Desire, which Evan Connell published last year. Informally and unsystematically, the two volumes cover a remarkable range of subjects. In sequential order, the essays in The WhiteLantern are about: developments in paleontology during the past several centuries, the mysteries surrounding the Etruscan civilization, the Norse Vinland voyages, the sinking of a 17th century Swedish dreadnaught, the exploration of Antarctica, attempts to decipher lost languages, and astronomy past and present.

The diversity of its subjects does not indicate the full diversity of Connell's book, because Connell has mastered the art of digression. We learn what can be called "mainline facts" from his book, fascinating odds and ends about various fields. We learn, for example, that Neanderthals probably stood as erect as modern man, and that our stereotype of a stooped and shambling half-ape developed because a skeleton reconstructed in 1908 just happened to be that of a very old male suffering from severe arthritis, a quirk that misled professionals as well as laymen for many years. But in passing we also learn many little offbeat facts, usually about the geniuses and eccentrics who are Connell's favorite subjects facts that suggest how comic, perverse, delightful, and admirable is humanity. For example, we learn about Didier Henrion, a 17th-century French engineer who stated flatly that Adam stood 123 feet 9 inches tall, Eve exactly five feet shorter. "What we would like to know most of all," Connell comments, "is why he positioned himself so awkwardly in the path of common sense."

Typically, while giving an informative account of developments in astronomy, Connell allows himself the luxury of three pages on the story of Guillaume Joseph Hyacinthe Jean Baptiste Le Gentil. In 1761, the French government dispatched Le Gentil to Pondicherry to observe the transit of Venus across the sun. Pondicherry, he discovered when he reached Mauritius, was besieged by the English, but he was allowed to join a French fleet that was supposed to raise the siege. A hurricane struck the fleet, and he almost drowned. Ashore after the storm, he suffered terrible dysentery while he waited for permission from the French Academy to observe the transit from Batavia rather than Pondicherry. When another fleet set sail for Pondicherry before he heard from the Academy, he joined it, but at sea the commander of the fleet heard that Pondicherry had surrendered to the English. Le Gentil had to observe the transit ineffectively from a rolling ship.

On his return to Mauritius, he tried to book passage back to France, but no ships were sailing. He decided to wait eight years there to observe the next transit, but then concluded that it would be better to observe it from Manila, 4,000 miles away. Without waiting for permission from the Academy, he sailed to Manila, but several years after his arrival the Academy notified him that he should observe the 1769 transit from Pondicherry, and that the English would cooperate. Le Gentil returned all the way to Pondicherry, set up his telescope, and on a beautiful clear morning awaited the transit. Ten minutes before the great event, a single cloud appeared, moved across the sun, and stayed there just long enough to obscure the transit. Even then, Fate was not through with Le Gentil. He finally returned to France, after 12 years of futile wandering, only to discover that his estate was being liquidated. Everyone had assumed that he was dead.

Cornell's disgressions, such as that on Le Gentil, obviously delight him as much as they delight the reader. At one point in The WhiteLantern, Connell describes a bizarre scene in the austere calm of the British Museum when one George Smith looked up from a Mesopotamian tablet, announced loudly that he was the first person to read it in 2,000 years, and, striding back and forth, proceeded to strip off his clothing. Connell deplores the fact that no one kept a record of what happened next. "Such details, like fine plums, ought to be plucked and tenderly boxed," he remarks. In his two volumes he has plucked and boxed many such plums.

And the digressions are actually less digressive than they appear; they usually reinforce the theme which informs the book as a whole. Connell's main subject in both A LongDesire and The White Lantern is endeavor the human capacity to persist with obsessive, often absurd, drive after goals that sometimes are magnificent, sometimes ridiculous. If accomplishment results from the endeavor, well and good. But even in failure, Connell implies, there is accomplishment in the endeavor itself as an exercise of the human spirit. Such an attitude could be sentimental, upbeat in a Victorian mode ("a man's reach should exceed his grasp"), but in The White Lantern Connell often takes a wry attitude towards his subjects. Somehow by a neat tonal balancing act he manages to laugh about much of what he relates while preserving an underlying lyrical joy in human energy and ingenuity, however misguided.

And at times in the book, the lyricism prevails. Objects, especially objects from the deep past, are magical for Connell, evoking the mystery of individual lives and of whole cultures long gone. In his essay on the Etruscans, writing mainly on the basis of the culture's relics, he weaves fact and speculation together, and concludes with a superb quotation that poetically captures the pastness of the past and its ultimate elusiveness. A Roman art dealer recalls how as a little boy he watched the sarcophagus of a Tarquinian nobleman being opened:

"Inside the sarcophagus I saw resting the body of a young warrior in full accoutrements, with helmet, spear, shield, and greaves. Let me stress that it was not a skeleton I saw; I saw a body, with all its limbs in place, stiffly outstretched as though the dead man had just been laid in the grave. It was the appearance of but a moment. Then, by the light of the torches, everything seemed to dissolve. The helmet rolled to the right, the round shield fell into the collapsed breastplate of the armor, the greaves flattened out at the bottom of the sarcophagus, one on the right, the other on the left. At the first contact with air the body which had lain inviolate for centuries suddenly dissolved into dust. ... In the air, however, and around the torches, a golden powder seemed to be hovering."

Ckauncey Loomis, professor of English, hashimself had occasion to observe and record"the human capacity to persist," most notablyas a member of several exploratory expeditionsto arcane places on our globe and as author of abook on the arctic explorations of CharlesFrancis Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

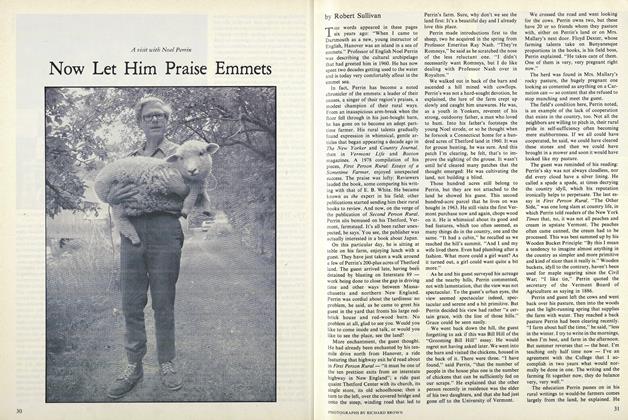

FeatureNow Let Him Praise Emmets

November 1980 By Robert Sullivan -

Feature

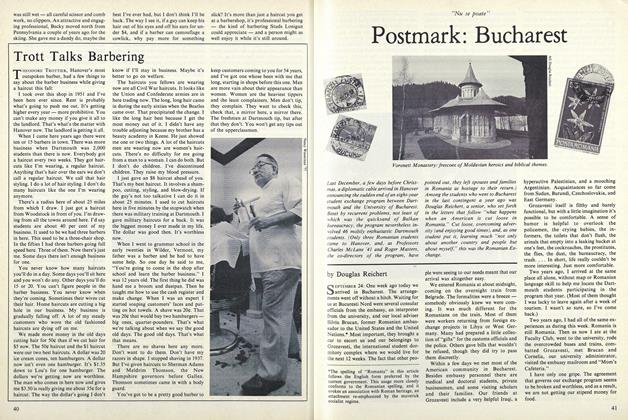

FeaturePostmark: Bucharest

November 1980 By Douglas Reichert -

Article

ArticleTrusteeship and the Alumni

November 1980 -

Article

ArticleUnofficial Arbiter

November 1980 By Patricia Berry '81 -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66

Chauncey C. Loomis Jr.

Books

-

Books

BooksECONOMICS

MAY 1930 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

October 1942 -

Books

BooksTHE NORTHWEST FUR TRADE

November 1928 By A. H. B. -

Books

BooksThis Side of Paradise

DECEMBER 1982 By Berl Bernhard '51 -

Books

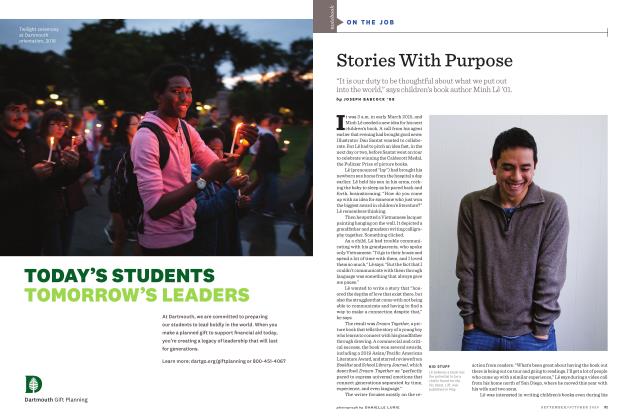

BooksStories With Purpose

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By JOSEPH BABCOCK '08 -

Books

BooksTHE BOOK OF FLORIDA FISHING FRESH SALT WATER

March 1957 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26