ABBOTT MEADER '57 is a visual artist with little patience with categories. He's a painter, a filmmaker, a potter, in neither that nor any other order. He is also a teacher, an entrepreneur, and a zealous fisherman. His priorities examined and ordered, he lives by undeniable wit and acknowledged talent, with his wife and three children, as autonomous a life as many of his Maine forebears.

"Categories again," he grumbles good-naturedly at any inquiry, however oblique, as to which of his "visual arts" he prefers. He has been painting and drawing since childhood, but "part of me sees in film . . . another way of looking at things. Certain images can only be generated by film."

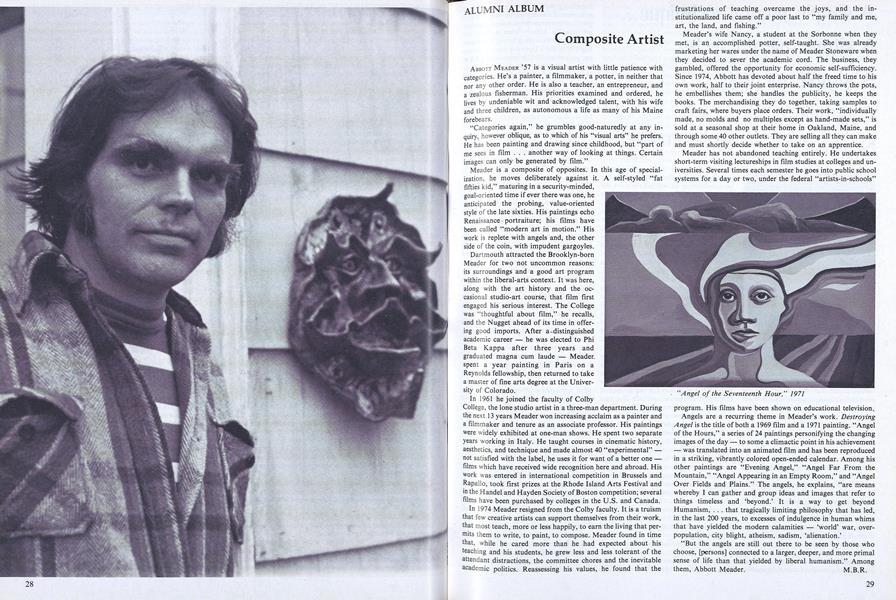

Meader is a composite of opposites. In this age of specialization, he moves deliberately against it. A self-styled "fat fifties kid," maturing in a security-minded, goal-oriented time if ever there was one, he anticipated the probing, value-oriented style of the late sixties. His paintings echo Renaissance portraiture; his films have been called "modern art in motion." His work is replete with angels and, the other side of the coin, with impudent gargoyles.

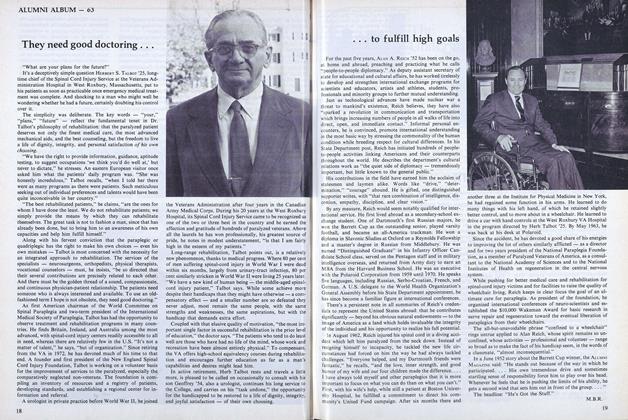

Dartmouth attracted the Brooklyn-born Meader for two not uncommon reasons: its surroundings and a good art program within the liberal-arts context. It was here, along with the art history and the occasional studio-art course, that film first engaged his serious interest. The College was "thoughtful about film," he recalls, and the Nugget ahead of its time in offering good imports. After a distinguished academic career — he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa after three years and graduated magna cum laude — Meader spent a year painting in Paris on a Reynolds fellowship, then returned to take a master of fine arts degree at the University of Colorado.

In 1961 he joined the faculty of Colby College, the lone studio artist in a three-man department. During the next 13 years Meader won increasing acclaim as a painter and a filmmaker and tenure as an associate professor. His paintings were widely exhibited at one-man shows. He spent two separate years working in Italy. He taught courses in cinematic history, aesthetics, and technique and made almost 40 "experimental" — not satisfied with the label, he uses it for want of a better one — films which have received wide recognition here and abroad. His work was entered in international competition in Brussels and Rapallo, took first prizes at the Rhode Island Arts Festival and in the Handel and Hayden Society of Boston competition; several films have been purchased by colleges in the U.S. and Canada.

In 1974 Meader resigned from the Colby faculty. It is a truism that few creative artists can support themselves from their work, that most teach, more or less happily, to earn the living that permits them to write, to paint, to compose. Meader found in time that, while he cared more than he had expected about his teaching and his students, he grew less and less tolerant of the attendant distractions, the committee chores and the inevitable academic politics. Reassessing his values, he found that the frustrations of teaching overcame the joys, and the institutionalized life came off a poor last to "my family and me, art, the land, and fishing."

Meader's wife Nancy, a student at the Sorbonne when they met, is an accomplished potter, self-taught. She was already marketing her wares under the name of Meader Stoneware when they decided to sever the academic cord. The business, they gambled, offered the opportunity for economic self-sufficiency. Since 1974, Abbott has devoted about half the freed time to his own work, half to their joint enterprise. Nancy throws the pots, he embellishes them; she handles the publicity, he keeps the books. The merchandising they do together, taking samples to craft fairs, where buyers place orders. Their work, "individually made, no molds and no multiples except as hand-made sets," is sold at a seasonal shop at their home in Oakland, Maine, and through some 40 other outlets. They are selling all they can make and must shortly decide whether to take on an apprentice.

Meader has not abandoned teaching entirely. He undertakes short-term visiting lectureships in film studies at colleges and universities. Several times each semester he goes into public school systems for a day or two, under the federal "artists-in-schools" program. His films have been shown on educational television.

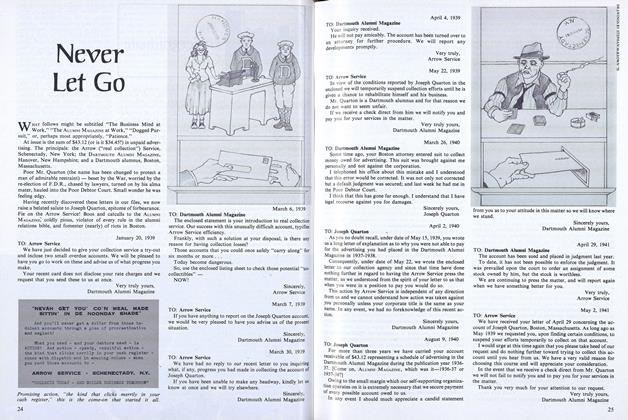

Angels are a recurring theme in Meader's work. DestroyingAngel is the title of both a 1969 film and a 1971 painting. "Angel of the Hours," a series of 24 paintings personifying the changing images of the day — to some a climactic point in his achievement — was translated into an animated film and has been reproduced in a striking, vibrantly colored open-ended calendar. Among his other paintings are "Evening Angel," "Angel Far From the Mountain," "Angel Appearing in an Empty Room," and "Angel Over Fields and Plains." The angels, he explains, "are means whereby I can gather and group ideas and images that refer to things timeless and 'beyond.' It is a way to get beyond Humanism, . . . that tragically limiting philosophy that has led, in the last 200 years, to excesses of indulgence in human whims that have yielded the modern calamities — 'world' war, overpopulation, city blight, atheism, sadism, 'alienation.'

"But the angels are still out there to be seen by those who choose, [persons] connected to a larger, deeper, and more primal sense of life than that yielded by liberal humanism." Among them, Abbott Meader.

"Angel of the Seventeenth Hour," 1971

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureNever Let Go

February 1977 -

Feature

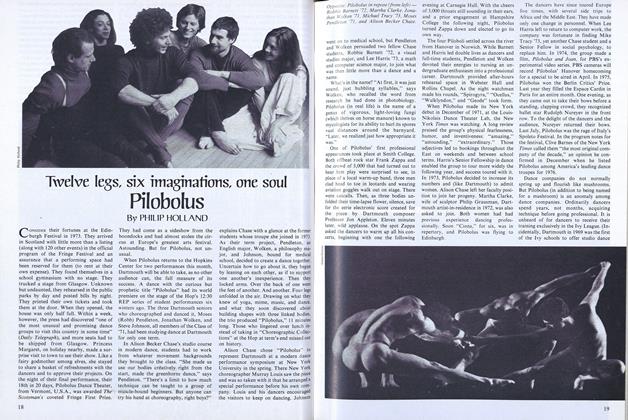

FeatureTwelve legs, six imaginations, one soul Pilobolus

February 1977 By PHILIP HOLLAND -

Article

ArticleStepping Out with a Bounder

February 1977 By D.M.N. -

Article

ArticleGray Is Beautiful

February 1977 By ELIZABETH CRONIN '77 -

Article

ArticleBittersweet Memories

February 1977 By ROBERT J. ZOVLONSKY '58

M.B.R.

Features

-

Feature

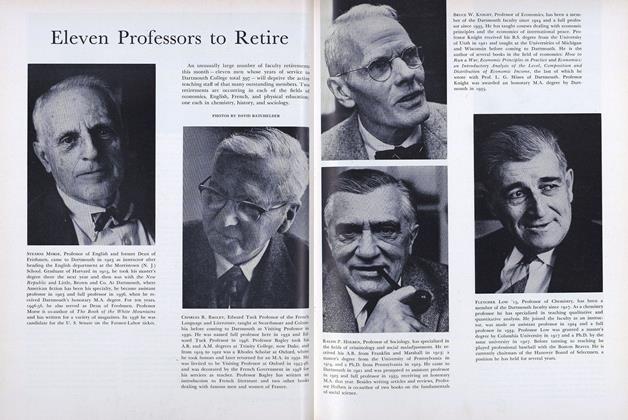

FeatureEleven Professors to Retire

June 1960 -

Feature

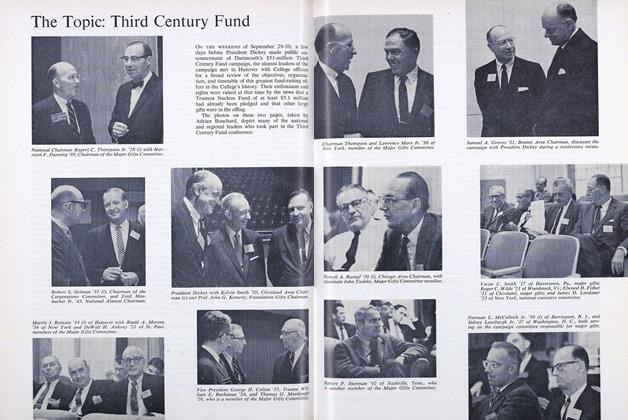

FeatureThe Topic: Third Century Fund

NOVEMBER 1967 -

Feature

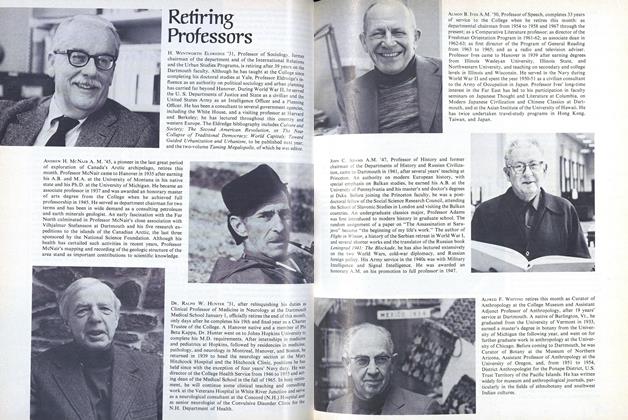

FeatureRetiring Professors

June 1974 -

Feature

FeatureThe Parent Trap

Mar/Apr 2011 -

Feature

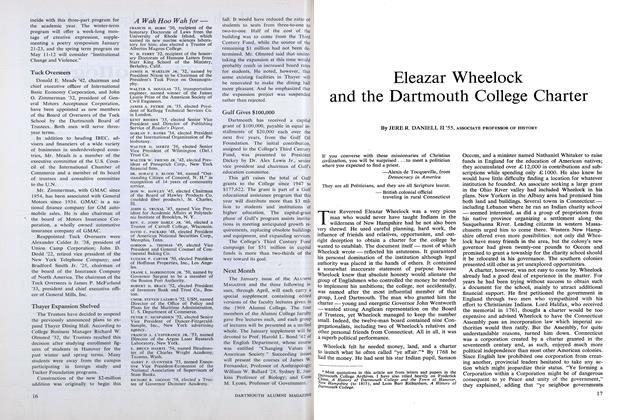

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

DECEMBER 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55 -

Feature

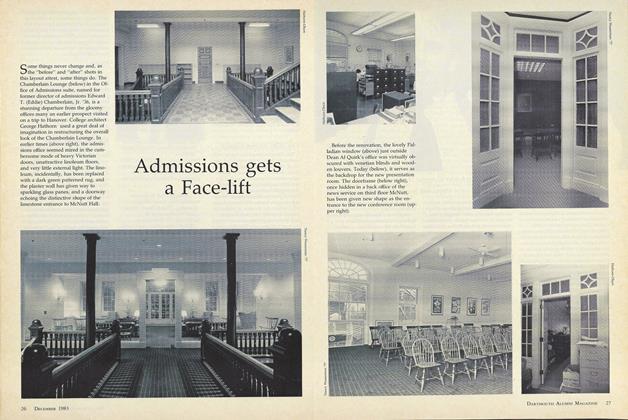

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

DECEMBER 1983 By Nancy Wasserman