Sure things at Saratoga in August are as scarce as uncashed $100 winning tickets at the track, but one certainty you can count on is a local product, the Hand melon, nurtured and coddled to maturity by AARON ALLEN HAND '43 on his farm in Greenwich, New York, some ten miles east of the spa.

Aristocrat of the breakfast - or banquet - table, the succulent cantaloupe has been grown by the Hand family for half a century, the height of its harvest ideally coinciding - though by no means coincidentally - with the four short weeks the fillies and the colts are breaking hearts and bankrolls on the Saratoga track.

"Tuss" Hand's father, looking for a fast cash crop to supplement his dairy operation, planted his first acre of melons in 1925 in the sandy soil of the lush farm country west of the Green Mountains. As gourmet told gourmet, the fame of the fruit, its distinctive Red Hand label testimony to its quality, spread and the business grew until 25 acres were devoted to its culture. In 1971 well over 8,000 bushels were harvested, each melon handpicked and individually inspected to see whether it had earned the supreme badge of the Red Hand.

The farm's roadside stand takes top priority and accounts for one third of the dollar volume of the business. Summer residents and tourists come year after year; racing fans stop, pockets still fall, on their way to the track, or blow winnings or console themselves after losses on their way home. Mrs. Hand runs a brisk mail-order trade, with melons timed for ripeness on arrival dipped as far as Florida and Oregon. Posh clubs and eating establishments in New York and Boston are standing customers; Hand melons have graced the White House table; and au point fruit is delivered each morning to the classy clubhouses, the hotels, and restaurants of Saratoga.

Diamond Jim Brady and Lillian Russell were born too early for the Hand melon, but Vanderbilts, Whitneys, and Paysons regularly dispatched their chauffeurs for the day's supply; Bernard Baruch liked to sit on the farmhouse porch and exchange views with the elder Hand, and Governor Dewey was a regular visitor. Although the carriage trade has dimmed since the glory days of the spa, the limousines still roll in from the great houses, and a new breed of big spender has arisen. This past summer, Hand recalls, one man - possibly fresh from picking a long shot on the nose - pulled up at the stand, opened the cavernous trunk of his big car, and asked how much it would cost to fill it. Undaunted by a fast $300 estimate, he drove off happily, tailpipe dragging.

"We've built up a reputation that's almost infallible," says Hand in explanation of his melon's popularity. It's not the varieties, which are readily available from commercial seed firms, and he discounts the nature of the soil. He attributes the mystique only to reliability born of meticulous culture and unwavering standards. The Hand melon's reputation is guarded as zealously as that of Caesar's wife, from late April, when the seeds are planted in individual pellets in the greenhouse; through planting on plastic mulch in fields that have grown other rotation crops for four or five years; through the wax-paper caps that protect the tender plants from late frost and too much sun early in their growth; through weekly dusting from the air; through scrutiny of the fields - "literally by the minute" - as the fruit is harvested, to insure that no melon from a deficient vine, no matter how sound in appearance, becomes eligible for the Red Hand; to the packing shed, where high-school crews are indoctrinated with the motto, "when in doubt, throw it out."

From late in July, when easy separation from the vine signifies that the first melon has come to maturity, till the yield dwindles to nothing about mid-September, the farm day is "long enough to harvest what's ready" - at season's peak occasionally from 6 a.m. till 5 p.m. But other farm work goes on year-round, two fulltime staff members helping the Hands with acres of feed corn, winter squash, wheat, sweet corn, and soybeans and a herd of some 100 dairy heifers boarded for neighboring farmers.

By agreement with his father, Hand spent two years at Dartmouth, then went to Cornell for agricultural training. "It was a sad day when I had to leave," he remembers, but he's remained a loyal and active alumnus. After three years in the Army, he returned to the farm, "cut the wood, sawed it, and built my house," just down the road from his parents'. Although he claims modestly only to have kept the operation going since his father's death 11 years ago, he's expanded the melon acreage, brought it to 50 per cent mechanization, maintained a continuous search for better new hybrid varieties, discontinued marginal farm enterprises and introduced others.

Why farming, a gamble his father warned him made the men who put their money on the ponies at Saratoga look like pikers? "It's all I know; I've done it all my life," Hand says simply.

Surveying his land from a battered Jeep, Peter the Springer Spaniel right-seat driving, Mushie the St. Bernard stretched languidly the width of the rear seat, Hand muses about the satisfactions, finding them hard to articulate. Part of it, he says, is "the marvelous independence. I like to think I can pick up and go wherever I want whenever I want, although I never have and I never will." But primarily, "it's looking out over the fields at mid-season, when the crop is half to three-quarters grown, thinking they look pretty good, knowing that - whatever happens the final satisfaction or the final blame is mine. I love the soil, and I love working it and watching it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBefore the Revolution

October 1975 By ALBERT F. MONCURE JR., RONALD V. NEALE -

Feature

FeatureA Dialogue for Autumn

October 1975 By COREY FORD -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

October 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleThe College

October 1975 -

Article

ArticleThe Trolley Never Stopped Here

October 1975 By GEORGE W. HILTON

M.B.R.

-

Feature

FeatureGuatemalan Cane Raiser

APRIL 1973 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMan in the Flying Machine

November 1975 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleDown-East Argonaut

March 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleSire of the Sitcom

October 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticlePolicy Manager

November 1980 By M.B.R.

Article

-

Article

ArticleSMOKERS

March 1912 -

Article

ArticleHOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HONORS THE MEMORY OF SHERMAN BURROUGHS '94

April, 1923 -

Article

ArticleBASKETBALL

MARCH 1967 By DAVE MARTIN '54 -

Article

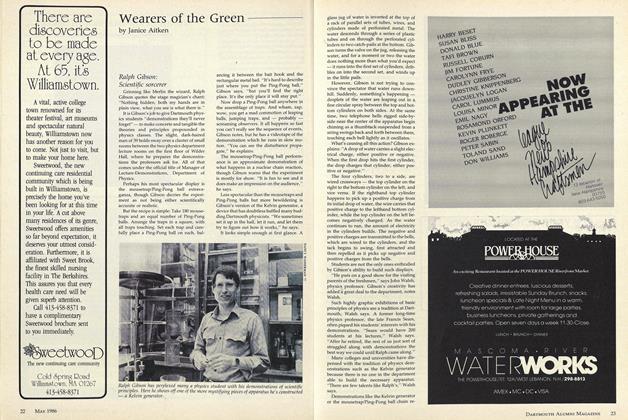

ArticleRalph Gibson: Scientific sorcerer

MAY 1986 By Janice Aitken -

Article

ArticleFaces to Watch

Jan/Feb 2004 By Julie Sloane '99 -

Article

ArticleA Lesson in Survival

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Lisa Campney '82