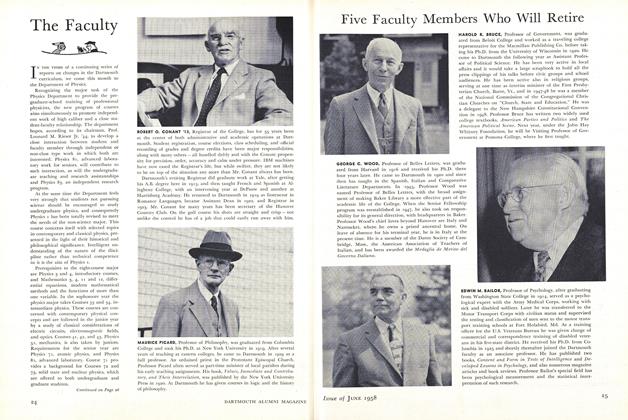

Speaking of items academic, we recently received the Freshman Seminar Program brochure. The course descriptions make fascinating reading. From the list of tantalizing titles we daydreamed over "The Spanish Armada," we philosophized about "The Palpable Dark: Self in the Crisis of Meaning," and we hummed along with "The World of the Musical Comedy." The freshman seminar, successful completion of which is a requirement for graduation, is intended to give the pea-green a taste of upper-level scholarship while further degreening her or his writing skills. With a class size of 16 or fewer, a heady reading list, and a minimum of 6,000 words of writing assigned, the seminar is usually an exhausting and exciting experience for newcomers to the Dartmouth grove. Hoping to find out a bit more about the nuts and bolts of a randomly selected seminar, we went to see Professor of Biology David Dennison, who teaches the perennially popular "Alternatives to Natural Selection: Genetic Engineering."

Its popularity, he told us, is a function of the contemporary and pressing nature of the subject matter, which includes such urgent public issues as the potential conflict between safety controls on recombinant DNA research and government limits on scholarly freedom of thought and inquiry. Taught in the fall, when only those freshmen who have been exempted from their beginning composition requirement can elect a seminar, the course, Dennison said, gets an interesting mix of future science majors, avowed pre-medical students, and students out to satisfy the science distributive requirement.

For these last, Dennison regards the seminar as "my chance to show them what science is really like, what scientists are really like." He finds that many students come to Dartmouth with warped notions of science, and his course, he thinks, is a good way of introducing them to it in a nonlaboratory situation.

Beyond the technical genetics material, the reading list includes books that stimulate discussion about the ethical implications of the uses of science. Huxley's Brave New World, a frightening vision of a genetically "pure' society, counterbalances research studies on potential cures for genetic diseases. Students are forced to confront the conflicting values that genetics research poses.

Dennison requires four short "think" essays and one long research paper for which students plunge into the professional literature on genetic disease. "If they can learn the jargon," he says, "they can come up with some very interesting essays." He sees his primary goal as the teaching of composition though he admits that he has no formal training in that field. If students need help beyond the basic mechanics of punctuation and grammar, he sends them to the writing resource center located in Sanborn House. The class members themselves help to teach one another, says Dennison: "We put a lot of effort into being critical about the way we argue; we insist that assertions should have supporting documentation."

Teaching a composition course in the sciences is a challenge, Dennison explains, because of the dearth of well-written material. Scientists often do not show enough concern with the way they express themselves, he feels, so he emphasizes this aspect of the course. The class, for instance, reads aloud from Lewis Thomas Lives of a Cell "because the prose is almost lyrical. The essays are much better read aloud than silently. Take a word like 'mitochondria'. . . . Besides, people have so little practice reading aloud. It's a rusty skill. And no one gets to fall asleep this way because they all have to read a paragraph."

Obviously, Dennison continues, the seminar is not typical of upper-level biology courses which normally consist of lecture and laboratory sessions. "It's a very intimate educational experience," he says of the seminar, and as a student moved on in his or her biology career, he or she would have to seek out a similar class determinedly.

Dennison enjoys the change of pace that teaching the seminar offers him.. "It's a chancy kind of teaching. I don't give lectures; I'm not imparting any specific body of knowledge. Tomorrow I'm going in and I'm not sure where we'll end up

sometimes it's as flat as a pancake. We re really at the mercy of group dynamics. But," he sums up, "I'm teaching the single most exciting topic in biology - the secret of life has been discovered."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAll the Way with J.B.A.

December 1980 By Frank Smallwood -

Feature

FeatureOnce Upon a Time

December 1980 -

Article

ArticleQuirkiness to Taste

December 1980 By Dana Cook Grossman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1966

December 1980 By RICK MAC MILLAN -

Article

ArticleMetaphysical Voyager

December 1980 By Robert H. Ross ’38 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1980 By RICHARD J. GOULDER