COMBINED OPERA TIONSIN THE CIVIL WARby Professor Rowena ReedNaval Institute Press, 1978. 375 pp. $16.95

Every historian writes to expand our knowledge, but to say something original about America's most written-about war is a challenge. Professor Rowena Reed has succeeded. She examines operations "requiring strategic or tactical cooperation between naval and land forces under separate command." Such campaigns were a major part of the Civil War, ranging from assaults on Confederate seacoast defenses to the campaigns on the western river systems. As she notes in the preface, it is hard to believe, but nevertheless true, that no one has treated this subject before. There have been narrative accounts, but Reed is the first to try to examine the most important battles and campaigns to see what thought, if any, Union leaders gave to the special problems of combined operations or their possible role in the defeat of the rebellion.

Reed's main thesis is that combined operations were a potential means for the North to win the war quickly and with a minimum of bloodshed and bitterness. The North had an overwhelming superiority at sea, much greater than on land. The Confederacy was an area with a long seaboard pierced by many navigable rivers, an ideal target for a strategy of combined operations. But the North never fully exploited these advantages, largely because the Federal war effort was too confused administratively, and too few officers appreciated the possibilities.

One of the few who did see this strategic opportunity was Major General George B. McClellan. During his brief tenure as commanding general, he conceived a single, comprehensive plan for the defeat of the Confederacy. In addition to controlling the most important seaports, the North would send waterborne expeditions reaching inland to seize the most important railroad junctions. With the Union controlling the Confederate communications network, the Southern armies must either disperse for lack of supplies or destroy themselves in costly assaults to recover these strategic points.

When McClellan was removed from the chief command, his strategy went with him and none replaced it. Instead, each general in each department operated in a strategic vacuum. As Reed notes, even if one disagrees with McClellan's strategy, surely it was better than none. However, she denigrates the abilities of Ulysses Grant to such an extent that she fails to see that when he became commanding general, he did have a unified strategy that successfully defeated the South.

This is one of the most stimulating Civil War volumes in many years. There is certainly much to disagree with, as this reviewer does. The presentation of McClellan and his strategy is too generous, overlooking his failures as a battlefield commander and the practical difficulties in his strategy. There are a few errors of detail, some minor (the Tombigbee River is misspelled in the text and the index), some more important (two railroads, the Richmond and Petersburg and the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac, are confused throughout one chapter). But none of this detracts from the major achievement of this book: It presents a new interpretation of Civil War strategy and a history of a previously neglected aspect of operations. That is what scholarship is all about.

Thomas English, who teaches at the DelawareCounty Community College in Pennsylvania, isa specialist in the history of the Civil War.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

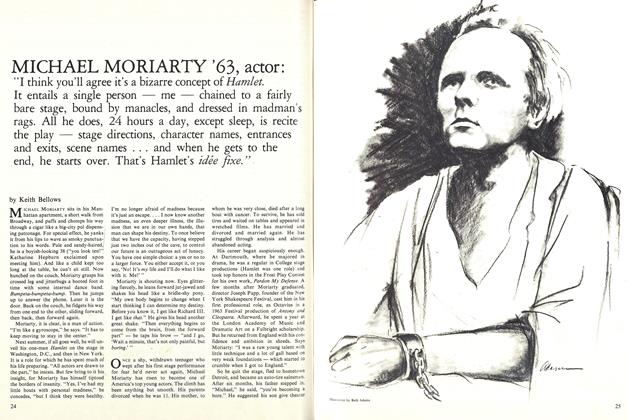

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Books

-

Books

BooksA WAYFARER IN PORTUGAL

JUNE, 1928 By Ernest R. Greene -

Books

BooksTHE COMPLETE STAYMAN SYSTEM OF CONTRACT BIDDING

May 1956 By FREDERICK PIERCE '01 -

Books

BooksMICHELANGELO, THE MAN

June 1935 By Hugh S. Morrison -

Books

BooksTall Tale

June • 1985 By M.W. -

Books

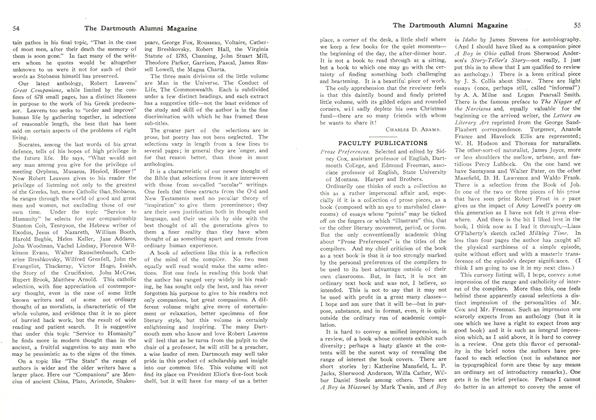

BooksProse Preferences.

NOVEMBER 1927 By Stearns Morse -

Books

BooksTHE BROWN DECADES.

MARCH 1932 By W. K. Stewart