THE scene is Lafayette Street in New York City, ten blocks or so of it, from Cooper Union to Middle Soho. The time is a bitterly cold Friday in January, four days into a new decade. The characters are an aging paper-pusher, a young sculptor, and a still younger playwright. For all three it is a red-letter day. The sculptor has his first New York gallery opening that evening. The playwright has the satisfaction of knowing that the "Arts and Leisure" section of the Sunday Times going through the presses that morning contains a major article about him and his work. For me it brings the first enjoyment of a particularly sweet experience, of being with young friends whom one has admired "from the beginning," in the context of their new success.

I must be careful not to overstate it. I cannot claim to be, or ever to have been, very close to either of them. I never taught them anything. It certainly did not take very much in the way of a talent for spotting talent to know that they were exceptional, even way back then, for they really were exceptional, not late bloomers or the kind who hid their lights under a bushel. Still, there is something singular about the evening, in that the Robert Freidus Gallery is at one end of Lafayette Street and the Public Theater (Joe Papp's place) is at the other, and I know the two men whose work is appearing in them. I guess I'm the only person on Lafayette Street that night who knows both of them. And (perhaps the source of the sweetness) I kriow that they know that I have taken them seriously, treated them with the respect due to artists, from the first.

They are serious men. They take themselves seriously; always have. Not in that objectionable way that goes with an absence of self-assessment or a lack of a sense of humor, but in the best way a man can take himself seriously: They believe that the principal ways they spend their time have worth, mean something. And they are right. They are thoughtful; always have been. Both are craftsmen whose growing mastery of their crafts has always been put at the disposal of their vision, of their sense of order, of their morality. Both are people who work hard and meticulously and, in the end, when it matters, alone. As do all artists. Both are men with lively eyes and lively minds. And both are Dartmouth alumni.

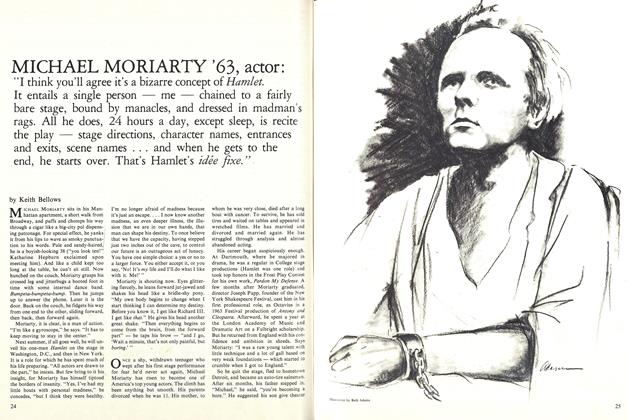

Of course, it isn't the first time I've admired the work of a Dartmouth alumnus-artist in New York. It's always been a source of pleasure, a generator of a thrill, when the opportunity comes, whether it's watching Michael Moriarty at the top of his form, or going to a film made by Joe Losey or Frank Gilroy or written by Buck Henry or Walter Bernstein, or enjoying a gallery full of Ralph Steiner's photographs, or marveling at the invention of the Pilobolus sextet, or reading a Burt Bernstein New Yorker piece at a New York lunch-counter, or wandering through Lo-Yi Chan's Henry Street Settlement extension. The list will surely get longer as the years go by (could already have been longer if I had been in the right places at the right times). But this evening shared between Stephan McKeown's exhibition and Peter Parnell's play is uniquely special for me.

One of the factors which make the evening different from most of the others is, of course, that most of those other artist-alumni had gone from Dartmouth before I arrived (Ralph Steiner had left more than ten years before I was born), and thus no part of the enjoyment of their work has the flavor of remembrance from this place. The only earlier experiences resembling this evening's were those which involved the men and women of Pilobolus, but with them it's a different difference: It's not that I never "knew them when ..." but rather that I have never known them, in the important sense of having looked them in the eye, talking with them of something really important. With Peter and Stephan, though (and with a few others over the years), there were those odd moments, moments which I expect are relatively numerous in the lives of good teachers, when all of one's attention was focused on a gifted student's achievement, a troubled student's problem, a curious student's questioning. Those moments create in the older person, I now know, a kind of concern for another's future, which in most people's lives is confined to members of one's family. And however dormant that concern may lie in the mulch of a million unrelated moments along the way, years later it can produce a shoot of joy which no one can know who has not been touched early on by a life with the promise of brilliance in it. That shoot of joy emerged from seeing the manifestations of two young men's achievement this night, and from thinking of myself as a representative of all who had offered any encouragement along the way.

"I'm glad you kept at it," I say to Stephan. "I couldn't do otherwise," he replies. Of course. And later, when I tell Peter of that exchange, he knows exactly what Stephan meant. Of course. It isn't ever easy to be a playwright or a sculptor. But, for a few people, there's no choice. It's appallingly difficult to get your work seen in anything like reasonable conditions in New York. Even having a foot in the door doesn't guarantee anything, doesn't even promise much. But it's obviously very good to have done it all the same.

Peter talks, over a beer, about the nourishment derived from the theater people during his years at Dartmouth students and faculty and the occasional administrator from their interdependence, from their support for one another. And I remember those years with him, thinking of the energy, the comings and goings in the warren at the northeast corner of the Hop. And I remember how, long ago, Stephan had told me how totally different his life here would have been without the chance to be alone in Hopkins Center. Talking to him brings back the pleasure that came from buying a painting by him from the first student art show I saw at Dartmouth, a painting I've since enjoyed every day of my working life.

At the end of the evening, I'm reminded that I'm not the only one who knows them both. "How's Matt Wysocki?" asks the playwright. I tell him. "I like Matt," he says. "When I was up there last summer he asked me the right question: 'Are you getting enough to eat, so that you can write?' " I may not be the only one who knows them both. But I'm the lucky one who saw them both that night, at opposite ends of Lafayette Street, glad to be where they are, who they are, what they are.

Peter Smith became director of Hopkins Center in 1969, whenStephan McKeown was a junior and Peter Parnell was thinkingabout coming to Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

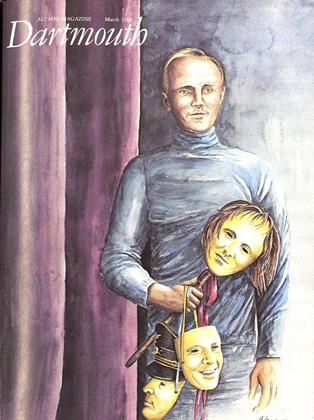

Cover Story

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

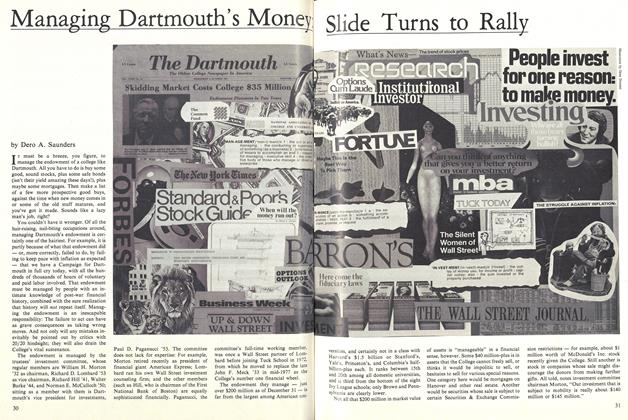

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Peter Smith

-

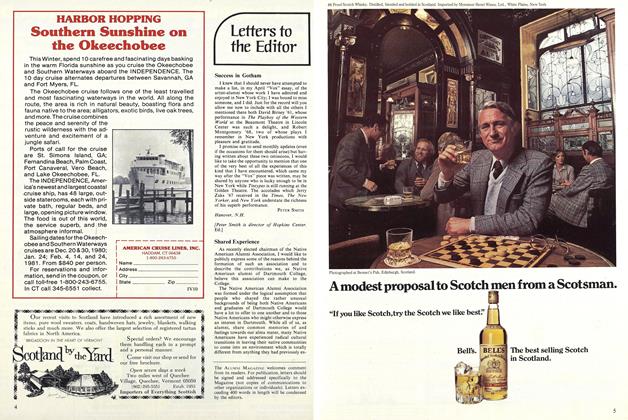

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1980 -

Article

ArticleCaution: Explosive Device

NOVEMBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

DECEMBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleHalf a Day in the Life of...

APRIL 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

OCTOBER 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith