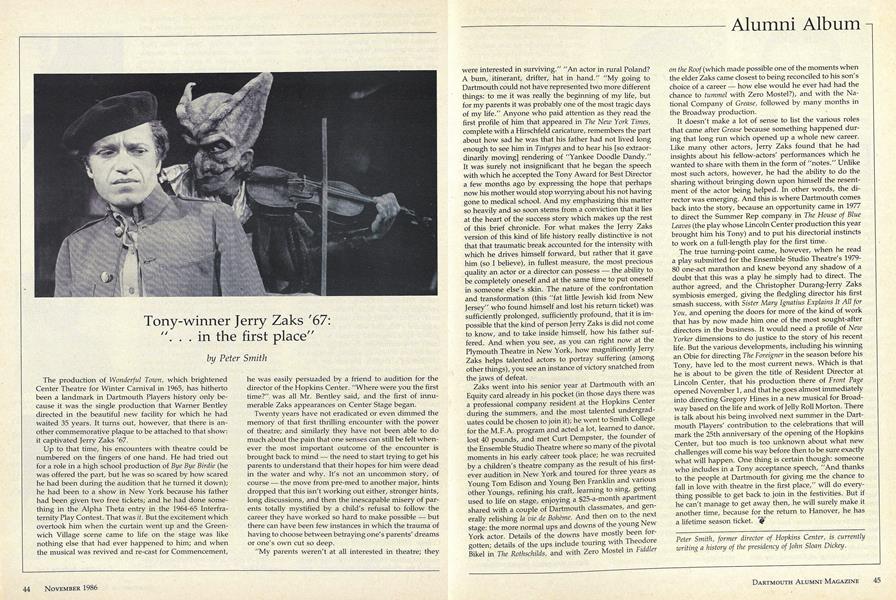

The production of Wonderful Town, which brightened Center Theatre for Winter Carnival in 1965, has hitherto been a landmark in Dartmouth Players history only because it was the single production that Warner Bentley directed in the beautiful new facility for which he had waited 35 years. It turns out, however, that there is another commemorative plaque to be attached to that show: it captivated Jerry Zaks '67.

Up to that time, his encounters with theatre could be numbered on the fingers of one hand. He had tried out for a role in a high school production of Bye Bye Birdie (he was offered the part, but he was so scared by how scared he had been during the audition that he turned it down); he had been to a show in New York because his father had been given two free tickets; and he had done something in the Alpha Theta entry in the 1964-65 Interfraternity Play Contest. That was it. But the excitement which overtook him when the curtain went up and the Greenwich Village scene came to life on the stage was like nothing else that had ever happened to him; and when the musical was revived and re-cast for Commencement, he was easily persuaded by a friend to audition for the director of the Hopkins Center. "Where were you the first time?" was all Mr. Bentley said, and the first of innumerable Zaks appearances on Center Stage began.

Twenty years have not eradicated or even dimmed the memory of that first thrilling encounter with the power of theatre; and similarly they have not been able to do much about the pain that one senses can still be felt whenever the most important outcome of the encounter is brought back to mind the need to start trying to get his parents to understand that their hopes for him were dead in the water and why. It's not an uncommon story, of course the move from pre-med to another major, hints dropped that this isn't working out either, stronger hints, long discussions, and then the inescapable misery of parents totally mystified by a child's refusal to follow the career they have worked so hard to make possible but there can have been few instances in which the trauma of having to choose between betraying one's parents' dreams or one's own cut so deep.

"My parents weren't at all interested in theatre; they were interested in surviving." "An actor in rural Poland? A bum, itinerant, drifter, hat in hand." "My going to Dartmouth could not have represented two more different things: to me it was really the beginning of my life, but for my parents it was probably one of the most tragic days of my life." Anyone who paid attention as they read the first profile of him that appeared in The New York Times, complete with a Hirschfeld caricature, remembers the part about how sad he was that his father had not lived long enough to see him in Tintypes and to hear his [so extraordinarily moving] rendering of "Yankee Doodle Dandy." It was surely not insignificant that he began the speech with which he accepted the Tony Award for Best Director a few months ago by expressing the hope that perhaps now his mother would stop worrying about his not having gone to medical school. And my emphasizing this matter so heavily and so soon stems from a conviction that it lies at the heart of the success story which makes up the rest of this brief chronicle. For what makes the Jerry Zaks version of this kind of life history really distinctive is not that that traumatic break accounted for the intensity with which he drives himself forward, but rather that it gave him (so I believe), in fullest measure, the most precious quality an actor or a director can possess the ability to be completely oneself and at the same time to put oneself in someone else's skin. The nature of the confrontation and transformation (this "fat little Jewish kid from New Jersey" who found himself and lost his return ticket) was sufficiently prolonged, sufficiently profound, that it is impossible that the kind of person Jerry Zaks is did not come to know, and to take inside himself, how his father suffered. And when you see, as you can right now at the Plymouth Theatre in New York, how magnificently Jerry Zaks helps talented actors to portray suffering (among other things), you see an instance of victory snatched from the jaws of defeat.

Zaks went into his senior year at Dartmouth with an Equity card already in his pocket (in those days there was a professional company resident at the Hopkins Center during the summers, and the most talented undergra uates could be chosen to join it); he went to Smith College for the M.F.A. program and acted a lot, learned to dance, lost 40 pounds, and met Curt Dempster, the founder o the Ensemble Studio Theatre where so many of the pivotal moments in his early career took place; he was recruite by a children's theatre company as the result of his firstever audition in New York and toured for three years as Young Tom Edison and Young Ben Franklin and various other Youngs, refining his craft, learning to sing, getting used to life on stage, enjoying a s2s~a-month apartment shared with a couple of Dartmouth classmates, an gen erally relishing la vie de Boheme. And then on to t e nex stage: the more normal ups and downs of the young ew York actor. Details of the downs have mostly been torgotten; details of the ups include touring with Thecgpre Bikel in The Rothschilds, and with Zero Mostel m Fiddleron the Roof (which made possible one of the moments when the elder Zaks came closest to being reconciled to his son s choice of a career how else would he ever had had the chance to tummel with Zero Mostel?), and with the National Company of Grease, followed by many months in the Broadway production.

It doesn't make a lot of sense to list the various roles that came after Grease because something happened during that long run which opened up a whole new career. Like many other actors, Jerry Zaks found that he had insights about his fellow-actors' performances which he wanted to share with them in the form of "notes." Unlike most such actors, however, he had the ability to do the sharing without bringing down upon himself the resentment of the actor being helped. In other words, the director was emerging. And this is where Dartmouth comes back into the story, because an opportunity came in 1977 to direct the Summer Rep company in The House of BlueLeaves (the play whose Lincoln Center production this year brought him his Tony) and to put his directorial instincts to work on a full-length play for the first time.

The true turning-point came, however, when he read a play submitted for the Ensemble Studio Theatre's 197980 one-act marathon and knew beyond any shadow of a doubt that this was a play he simply had to direct. The author agreed, and the Christopher Durang-Jerry Zaks symbiosis emerged, giving the fledgling director his first smash success, with Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All forYou, and opening the doors for more of the kind of work that has by now made him one of the most sought-after directors in the business. It would need a profile of NewYorker dimensions to do justice to the story of his recent life. But the various developments, including his winning an Obie for directing The Foreigner in the season before his Tony, have led to the most current news. Which is that he is about to be given the title of Resident Director at Lincoln Center, that his production there of Front Page opened November 1, and that he goes almost immediately into directing Gregory Hines in a new musical for Broadway based on the life and work of Jelly Roll Morton. There is talk about his being involved next summer in the Dartmouth Players' contribution to the celebrations that will mark the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Hopkins Center, but too much is too unknown about what new challenges will come his way before then to be sure exactly what will happen. One thing is certain though: someone who includes in a Tony acceptance speech, "And thanks to the people at Dartmouth for giving me the chance to fall in love with theatre in the first place," will do everything possible to get back to join in the festivities. But if he can't manage to get away then, he will surely make it another time, because for the return to Hanover, he has a lifetime season ticket. Hp

Peter Smith, former director of Hopkins Center, is currentlywriting a history of the presidency of John Sloan Dickey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Reaffirmation of Mission

November 1986 By Raymond L. Hall -

Feature

FeatureHow "Eleazar" Pulled It Off

November 1986 By FRANK K. KAPPLER '36 -

Feature

FeatureThe New England Review and Bread Loaf Quarterly

November 1986 By Peter Mandel -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

November 1986 By Bob Monahan '29 -

Article

ArticleDavid O. Hooke '84: Chubber's Boswell

November 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Soccer

November 1986 By Jim Needham '70

Peter Smith

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

October 1980 -

Article

ArticleHello, Mr. Chips

March 1980 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: Who are the Arts for and, Indeed, Who Owns Dartmouth?

April 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

OCTOBER 1981 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleIn the Wide, Wide World

MARCH 1982 By Peter Smith -

Article

ArticleEndings and Beginnings

JUNE 1982 By Peter Smith

Article

-

Article

ArticleMR. GEORGE F. BAKER, DONOR OF NEW DARTMOUTH LIBRARY

DECEMBER 1926 -

Article

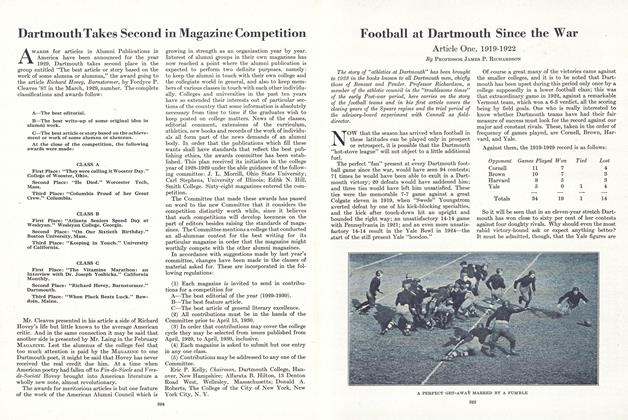

ArticleDartmouth Takes Second in Magazine Competition

MARCH 1930 -

Article

ArticleRadio Repeater

February 1942 -

Article

ArticleCommencement Program

May 1942 -

Article

ArticleResigns Pastorate

January 1952 -

Article

ArticleLACK OF TASTE

June 1935 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36