Late last fall, aiming to draw attention to the national problem of low-level radioactive waste disposal, Governors Dixy Lee Ray of Washington and Robert List of Nevada closed the disposal sites in their states to further waste shipments, and Governor Richard Riley of South Carolina ordered Chem-Nuclear Systems, Inc. of Barnwell, South Carolina, to cut its intake of radioactive materials in half. These moves effectively shut the only sites in the nation currently licensed by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to bury certain radioactive wastes. The governors were complaining that repeated violations of packaging regulations as many as 63 at Chem-Nuclear Systems during one threemonth period in 1979 had led to an alarming increase in the number of spills.

With no place to ship their wastes and only limited storage capacities, some scientific and medical research facilities (which produce nearly two-fifths of the nation's low-level wastes mostly contaminated clothing, instruments, and sludge) would have had to curtail their research projects if Governors Ray and List had not reopened the burial sites shortly after the closings. However, Governor Riley is still allowing Chem-Nuclear to accept only half of its former waste intake, and Governor Ray is threatening to close the Hanford, Washington, burial site again if there are no new sites opened by 1982.

Donald Penfield, associate dean for administration at the Medical School, and Dr. Alexander Filimonov, the College's radiation safety officer, recently explained how last fall's closing of the burial sites affected disposal of low-level wastes generated by Mary Hitchcock Hospital and the Medical School, and what plans had been made to deal with the possibility of another closing.

Low-level radioactive wastes produced by the Hitchcock-Medical School complex (mostly items like contaminated gloves, plastic containers, and spent syringes), which had normally been sent to Barnwell, South Carolina, were disposed at a federal facility at Galveston, Texas, made temporarily available during the problem period. If there had been nowhere to ship the wastes, interim storage facilities in the Hanover area could have accommodated the materials for at least five to six months. According to Penfield, the small volume of low-level radioactive wastes generated here only 160 55-gallon drums yearly (compared with 3,000 drums yearly at Yale) and their extremely low levels of radioactivity simplify the disposal problem. Penfield says the radioactivity levels are so low that the materials could, as a last resort, legally be buried on private property in New Hampshire, which was done at one time on a farm owned by the College in Lyme Center, but now all the materials are shipped away chiefly for public relations' reasons.

Looking ahead, legislation currently before Congress would create either 15 regional sites for the disposal of low-level wastes or require each state to build its own disposal center. At present, because of the comparatively small size of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and the limited nature of research carried on here, low-level radioactive waste disposal poses no great problem another of the advantages of being small.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

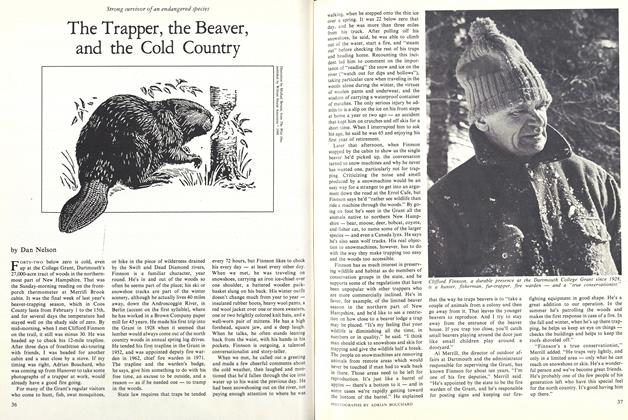

FeatureThe Trapper, the Beaver, and the Cold Country

March 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

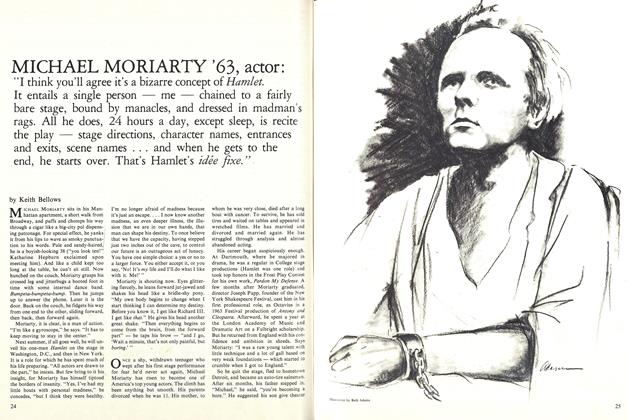

Cover StoryMICHAEL MORIARTY ’63, ACTOR

March 1980 By Keith Bellows -

Feature

FeatureManaging Dartmouth’s Money Slide Turns to Rally

March 1980 By Dero A. Saunders -

Article

ArticleTracker of the Right Stuff

March 1980 By M.B.R. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

March 1980 By CARL C. FORSAITH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

March 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS TO BE IN HANOVER THIS TERM

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleRE-ELECTED

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleThe Beginning

OCTOBER 1981 -

Article

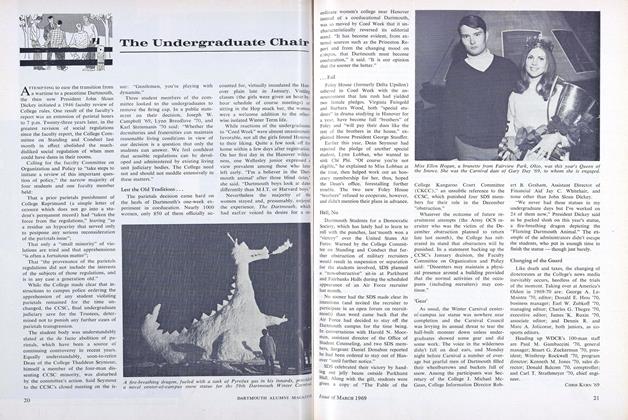

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MARCH 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Club

May 1940 By EDWARD McD. FRITZ '40 -

Article

ArticleRICHARD EBERHART: A Reader of the Spirit

June 1952 By JOHN W. FINCH