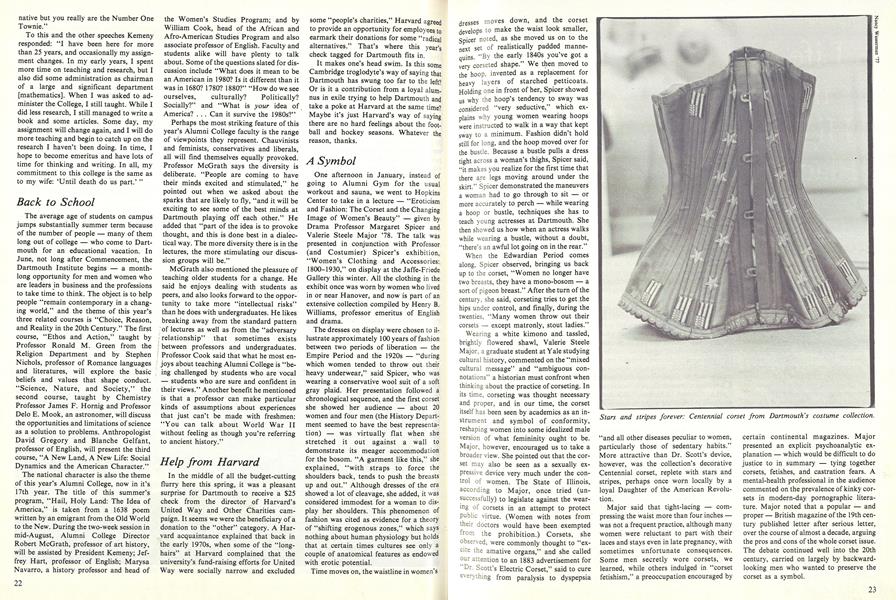

One afternoon in January, instead of going to Alumni Gym for the usual workout and sauna, we went to Hopkins Center to take in a lecture-"Eroticism and Fashion: The Corset and the Changing Image of Women's Beauty"-given by Drama Professor Margaret Spicer and Valerie Steele Major '78. The talk was presented in conjunction with Professor (and Costumier) Spicer's exhibition, "Women's Clothing and Accessories: 1800-1930," on display at the Jaffe-Friede Gallery this winter. All the clothing in the exhibit once was worn by women who lived in or near Hanover, and now is part of an extensive collection compiled by Henry B. Williams, professor emeritus of English and drama.

The dresses on display were chosen to illustrate approximately 100 years of fashion between two periods of liberation-the Empire Period and the 1920s-"during which women tended to throw out their heavy underwear," said Spicer, who was wearing a conservative wool suit of a soft gray plaid. Her presentation followed a chronological sequence, and the first corset she showed her audience-about 20 women and four men (the History Department seemed to have the best representation)-was virtually flat when she stretched it out against a wall to demonstrate its meager accommodation for the bosom. "A garment like this," she explained, "with straps to force the shoulders back, tends to push the breasts up and out." Although dresses of the era showed a lot of cleavage, she added, it was considered immodest for a woman to display her shoulders. This phenomenon of fashion was cited as evidence for a theory of "shifting erogenous zones," which says nothing about human physiology but holds that at certain times cultures see only a couple of anatomical features as endowed with erotic potential.

Time moves on, the waistline in women's dresses moves down, and the corset develops to make the waist look smaller, Spicer noted, as she moved us on to the next set of realistically padded mannequins. "By the early 1840s you've got a very corseted shape." We then moved to the hoop, invented as a replacement for heavy layers of starched petticoats. Holding one in front of her, Spicer showed us why the hoop's tendency to sway was considered "very seductive," which explains why young women wearing hoops were instructed to walk in a way that kept sway to a minimum. Fashion didn't hold still for long, and the hoop moved over for the bustle. Because a bustle pulls a dress tight across a woman's thighs, Spicer said, "it makes you realize for the first time that there are legs moving around under the skirt." Spicer demonstrated the maneuvers a woman had to go through to sit-or more accurately to perch-while wearing a hoop or bustle, techniques she has to teach young actresses at Dartmouth. She then showed us how when an actress walks while wearing a bustle, without a doubt, "there's an awful lot going on in the rear."

When the Edwardian Period comes along, Spicer observed, bringing us back up to the corset, "Women no longer have two breasts, they have a mono-bosom-a sort of pigeon breast." After the turn of the century, she said, corseting tries to get the hips under control, and finally, during the twenties, "Many women throw out their corsets-except matronly, stout ladies."

Wearing a white kimono and tassled brightly flowered shawl, Valerie Steele Major, a graduate student at Yale studying cultural history, commented on the "mixed cultural message" and "ambiguous connotations" a historian must confront when thinking about the practice of corseting. In its time, corseting was thought necessary and proper, and in our time, the corset itself has been seen by academics as an instrument and symbol of conformity, reshaping women into some idealized male version of what femininity ought to be. Major, however, encouraged us to take a broader view. She pointed out that the corset may also be seen as a sexually expressive device very much under the control of women. The State of Illinois, according to Major, once tried (unsuccessfully) to legislate against the wearing of corsets in an attempt to protect public virtue. (Women with notes from their doctors would have been exempted from the prohibition.) Corsets, she observed, were commonly thought to "excite the amative organs," and she called our attention to an 1883 advertisement for Dr. Scott's Electric Corset," said to cure everything from paralysis to dyspepsia "and all other diseases peculiar to women, particularly those of sedentary habits." More attractive than Dr. Scott's device, however, was the collection's decorative Centennial corset, replete with stars and stripes, perhaps once worn locally by a loyal Daughter of the American Revolution.

Major said that tight-lacing-compressing the waist more than four inches-was not a frequent practice, although many women were reluctant to part with their laces and stays even in late pregnancy, with sometimes unfortunate consequences. Some men secretly wore corsets, we learned, while others indulged in "corset fetishism," a preoccupation encouraged by certain continental magazines. Major presented an explicit psychoanalytic explanation-which would be difficult to do justice to in summary-tying together corsets, fetishes, and castration fears. A mental-health professional in the audience commented on the prevalence of kinky corsets in modern-day pornographic literature. Major noted that a popular-and proper-British magazine of the 19th century published letter after serious letter, over the course of almost a decade, arguing the pros and cons of the whole corset issue. The debate continued well into the 20th century, carried on largely by backwardlooking men who wanted to preserve the corset as a symbol.

Stars and stripes forever: Centennial corset from Dartmouth's costume collection.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

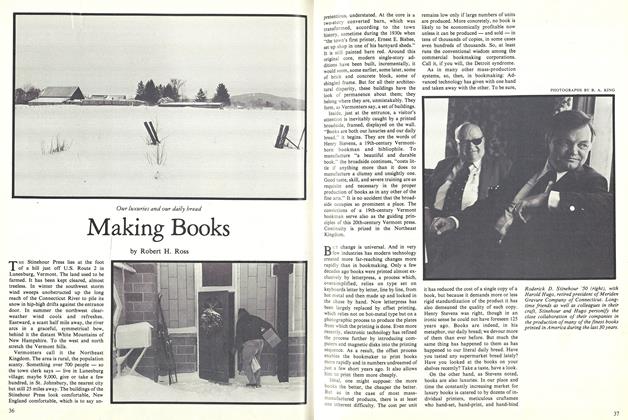

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

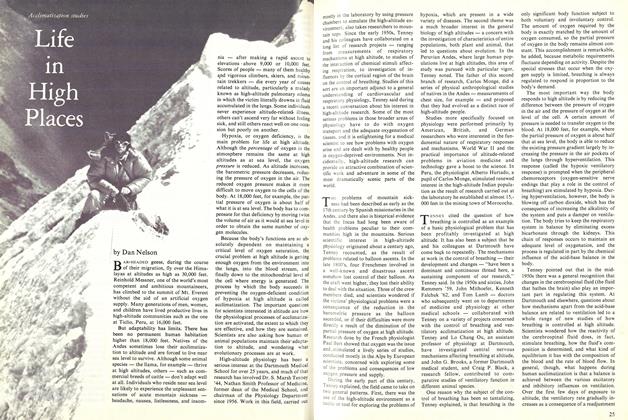

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT