It was January in Hanover, with snow flurries sifting down onto the strangely barren brown turf of the Green. But the ten students in Professor Wayne Broehl's freshman seminar were about to take off, in their imaginations, for an afternoon in Gaon a small village in India. There, Broehl told them, it was a dry midsummer day, sometime within the last decade. Although the caste system had been outlawed officially, he said, Gaon-like many other villages far removed from urban settings-still maintained a rigid, if informal, caste structure.

Benjamin Ames Kimball professor of administration at the Tuck School, Bro has been studying rural social change within the Asian subcontinent since 1965. He is one of a handful of associated-school professors who enjoy teaching freshmen in seminar on a more or less regular basis. This year's topic, in the Geography Department, is "India's Food Problem."

In Gaon, the students find a village about as wide as it is long, some 300 yards from the blacksmith's shop to the north to the temple priest's lodgings on the southern edge. It is experiencing a severe drought. One of the two wells in town-the one that members of the Brahman, Rajput, Maratha, and Ghadsi castes had traditionally used-has gone dry. The other well, traditionally used by the untouchables-mostly scavengers and leather workers has been appropriated by the higher caste members. This appropriation has forced the untouchables, who can no longer use their own well for reasons of religious purity, to get water at a well a mile's walk outside of the village on the road to the neighboring village of Vadi.

For the right to continue using their old well, the untouchables have decided to appeal to the village "panchayat," a judicial board composed of three landowners (two Rajputs, one Brahman) and One wealthy shopkeeper.

Having set the stage, Broehl cast the ten students, who had turned in short papers about the caste system at the start of class, into roles for a mock hearing of the panchayat. Three students became Brahman landowners, three became untouchables, and four became members of the village panchayat With characteristic enthusiasm, Broehl emphasized that the secret to a successful role-playing exercise was staying in the roles. Then he directed the three groups to split up into separate rooms for 20 minutes of preparation before coming together for the 20-minute hearing of the panchayat The entire exercise was videotaped so the class could replay and criticize its own performance in the second hour of the seminar.

The Brahmans and the untouchables worked on strategies for winning their respective cases, and the panchayat members spent their time modifying Robert's Rules of Order to fit the upcoming hearing. While discussing how best to play their roles, the students made continual reference to knowledge thay had gained from writing their papers. Broehl circulated among the rooms, answering questions. Then, with a warning that only two minutes of preparation time remained, he removed himself from the exercise by announcing to the panchayat, "Once the role-playing starts, it's all in your hands." The Brahmans and the untouchables assembled before the panchayat and the hearing began.

One of the Brahmans started off with a loud protest to the panchayat that the untouchables, who were sitting across the long table, should be made to sit farther away from the panchayat than the Brahmans, in keeping with the rules of the caste system. The spokesman for the panchayat granted this request and the hearing continued. The high-handed Brahmans presented legalistic, well-reasoned religious arguments, while the untouchables appealed to the emotions of the panchayat members, including a very convincing performance by one student who played the part of a lame woman. Once all the arguments had been heard, the panchayat took only a few minutes to decide the case. Consistent with the inequities of the caste system, the decision went against the untouchables.

During a coffee-break, while one student from Ghana chatted with another from Virginia in German and other students walked down the hall to buy soda in pink cans and cake in blue wrappers from red vending machines, Broehl commented that the role-playing exercise was an adaptation of exercises often used at the Tuck School to simulate business situations. Then the students reassembled to watch themselves on videotape. There was a good bit of friendly laughter and some constructive criticism from both Broehl and the students. Along with the learning, one and all seemed to be having a fine time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

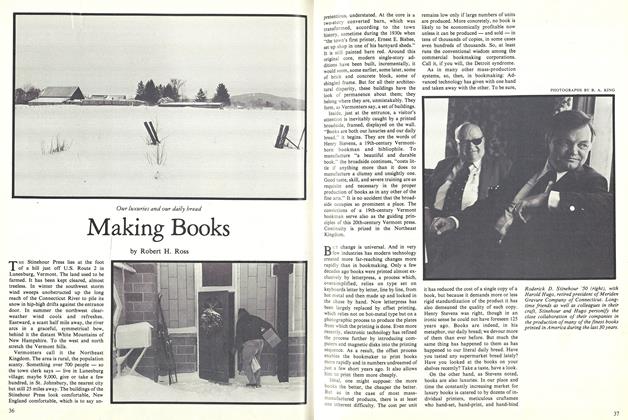

FeatureMaking Books

April 1980 By Robert H. Ross -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureExtra Credits & Bonus Points

April 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWho in Hell Was Jeff Tesreau?

April 1980 By Edward D. Gruen '31 -

Article

ArticleAdapting to the Heights

April 1980 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1980 By DAVID R. BOLDT

Article

-

Article

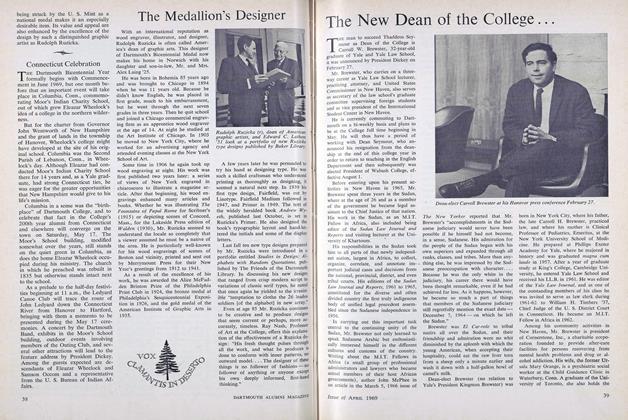

ArticleThe Medallion's Designer

APRIL 1969 -

Article

ArticleWearers of the Green

July 1974 -

Article

ArticleCold Calculations

MAY 1997 By Christopher Kenneally 81 -

Article

Article"They're Rooms — Not Units"

May 1961 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticlePROF'S CHOICE

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Professor Ron Edsforth -

Article

ArticleWho Is that Masked Man?

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Rianna P. Starheim ’14