The libraries • computing • Hopkins Center • OISER

In my five-year report I made the following remarks about our library: With its more than one million volumes, the Dartmouth Library is one of the largest open-stack libraries in the world. As one who has on occasion had to battle his way through closed-stack libraries, I can testify to the enormous pleasure of being able to browse on one's own in a first- rate collection. Without such an out- standing collection we could never attract the quality faculty that we do; therefore, it is our single most important asset in support of education.

It is also true that it is very ex- pensive for an institution of our size to maintain so remarkable a library. The net yearly cost is more than $1.5 million, and library costs are increas- ing more rapidly than for other pro- grams. This results from a combina- tion of unusually sharp cost increases in printing and the explosion of human knowledge. In our present financial situation we face difficult priority decisions, balancing what the institution can afford against the danger of compromising the quality of Baker Library.

A second major problem facing libraries is that as more and more volumes are published each year, the demand for physical space is ever increasing. While the first million volumes took 200 years to acquire, at current rates of acquisition the second million volumes will occur in 30 years. The construction of enor- mous new physical facilities and the cost of operating them could bank- rupt the College.

We have gained some time through the construction of the Feldberg Library serving Tuck and Thayer schools and the Kresge Library for the physical sciences, as well as through an addition to the Dana Biomedical Library. During the years of expansion made possible by these facilities, we must find a solution less disastrously expensive than keeping two or three million volumes in an open-stack library in the center of campus.

In the long run there is considerable hope that modern technology will come to the aid of libraries. Even today microtexts make it possible to store a million volumes in one large room. But the publishing industry has not made an appropriate adjustment, and libraries continue to have to buy most works in traditional form.

Thus, while I see hope in the long run, our libraries will not be able to wait until the day that technology comes to the rescue .... Dartmouth is also exploring cooperative ventures to share library resources with other institutions.

All of the above remarks are as true today as they were then, ex- cept that what was the future five years ago is now the present. It took Dartmouth College 200 years to acquire a million vol- umes for its libraries. In the past decade that number has in- creased by 25 per cent! We are rapidly running out of room, and to prevent prohibitively expen- sive construction and operating costs, we must move in the very near future with the construction of a warehouse for rarely used books.

The problems that have af- fected Dartmouth's library col- lection are shared by all major libraries in the country. In a report our librarian referred to the past as "the building of com- prehensive, self-sufficient col- lections contained in ever- expanding physical plants." That is no longer possible for any privately owned library. As our institutions enter a period of steady-state in which no expan- sion is possible, we cannot allow the library budget to take up an ever-increasing portion of the total budget. While I still hope that technology will significantly aid libraries in the long run, my prediction turned out to be correct that technological changes are coming too slowly to alleviate the immediate space problem.

After a quarter century of service to the Dartmouth libraries, Edward Connery Lathem '5l elected to step down from the posi- tion of librarian of the College. Our first intensive search did not produce a candidate we were prepared to name as the new librarian. We were therefore most fortunate to attract Virginia Whitney, a distinguished, recently retired librarian, as acting librarian of the College. In addition to superb service in this capacity, she helped us launch a more extensive search that this time had a very happy conclusion. The associate librarian of M.1.T., Margaret Otto, was named librarian of Dartmouth College in the spring of 1979.

Under her able leadership, a number of major planning efforts are under way. We are developing a comprehensive collection plan for the Dartmouth College Library. That is, we will make a series of conscious decisions as to what we will collect and what we will not collect, where we will attempt complete collections and where we will rely on cooperative arrangements to supple- ment our own holdings. Since it is financially impossible to buy everything that we would like to have in our own libraries, it is es- sential that we should have such a comprehensive plan.

We are fortunate to be one of 15 members of the Research Libraries Group, which represents the most ambitious effort to share resources among the major libraries and to help with joint planning efforts. This group is committed to a rational plan that will avoid unnecessary duplication of very expensive collections and allow access to the respective collections by all the members. Clearly, the savings in such a joint venture can be very significant. Through this group we are also involved in a cooperative effort to provide computerized information for cataloging of books and data-manipulation systems that will enormously aid services at each of the institutions. There is a joint program to develop the best and most efficient methods for the preservation of books. The group will also take a leadership role in trying to bring about nationwide cooperative relationships among libraries.

We are continuing pioneering efforts to bring computers to the aid of our library system. We now have in computer-readable form the data on all the materials acquired in the past three years, and this data base will steadily expand. The hope is that even- tually a computerized catalog system will completely replace the card catalog. There is the potential for vast savings for the institu- tion as well as the potential of providing quicker and more con- venient services for our users.

We are in the final planning stage for the building of a warehouse that could initially house a quarter of a million volumes. As new books continue to be acquired over the next decade, we will have to remove an equal number from the present collection. Most of these would be placed in the remote storage warehouse, from which they would be available in 24 hours on request. By intelligent selection of the books to be placed into such a warehouse, the call for such books should be minimal. We must also make some priority decisions as we cull our present selection as to whether some books are not worth keeping at all. I know that the discarding of a book sounds like a crime. But I happen to be aware of the fact that we own a huge collection of 19th-century trigonometry books. While three'or four such volumes may be worth keeping for future historical scholars, I can see no possible justification for keeping the entire collection.

We are painfully aware that these interim measures are expen- sive and not totally satisfactory. They must, however, tide us over until that happy day when modern technology comes to the rescue of research libraries. I still am convinced that some day a com- bination of computers and telecommunication will allow access from any library to the total collection of all libraries in a quick and painless manner. Only then will we have a truly satisfactory solution to the problem of research libraries.

I should like to conclude this section by quoting from a report by our new librarian: "The Dartmouth College Library reflects a richness and quality unequaled in like institutions. The collections have been built with intelligence and care. The members of the staff are competent and committed. Of all the many assets of Dartmouth College, I feel the library has to be one of its most precious, most valued possessions."

D y 1975, the Dartmouth Time Sharing System had K M achieved a deserved national (and international) reputation as probably the outstanding educational computing system in the world. I am dictating this section just before midnight on Valentine's Day. Before beginning the dicta- tion, I walked to the terminal in my home to find out how well our computing system did today. It has been in continuous operation since 6:30 a.m. and will continue to run until 3:00 a.m. tomorrow. During the day 3,735 users signed on to the system, and nearly 50,000 programs have been run. At the peak of the day, 213 different people were using the system at the same time. At mid- night, in spite of the late hour, 71 people were using the com- puting system. The system's record for being operational almost without fail and providing continuing and reliable service is one of the best in the nation. These statistics, which still sound miraculous to me, are totally taken for granted on campus.

After a decade of service, Thomas Kurtz, co-inventor of time- sharing and BASIC, stepped down as director of the Kiewit Com- putation Center. He was first replaced by John McGeachie '65, a distinguished computer scientist, who as an undergraduate played a key role in the development of time-sharing. When he decided to enter the industrial world, we were fortunate to attract William Arms from Great Britain as the new director. These two directors faced an enormous challenge in updating the quality of our equip- ment which, after a decade of excellent service, was dilapidated and out-of-date. In a two-step process we upgraded our system to a Honeywell 66/DTS-3 system, which has twice the power of our previous large computer and represents truly modern technology. We have also expanded the memory of the computer to the point where it can now hold a billion characters of information. That amount of information is the equivalent of a library of several thousand volumes, and the computer can make "any page in any book" available in a fraction of a second.

The major improvement in equipment was made possible by a combination of factors. An important factor was a further generous gift by Peter Kiewit '22. So was a significant educational discount by the manufacturer, Honeywell, in recogni- tion of the many contributions Dartmouth College has made to computing. The remainder is being amortized over a decade; our costs per user are still among the smallest in spite of the necessity of amortizing expensive equipment. These costs are further reduced by the continuing number of educational institutions that are our customers. Some 20 colleges and universities are regular customers, ranging from small New England colleges to Harvard University. Our most significant off-campus user currently is the Coast Guard Academy, which runs more than 30 terminals in our computing system. While we provide services to these customers at cost, they permit Dartmouth College to have a much larger system than it could afford alone.

In my previous report, I described the creation of DTSS (Dart- mouth Time Sharing System, Inc.), a marketing company for the software system developed by the College. For several years the existence of this company contributed significantly to the up- grading of the quality of software in our computing system. When the trustees made a determination that it was perhaps not ap- propriate for the College to be in such a commercial venture, we successfully sold the company, adding over a million dollars to the Dartmouth endowment. Our software development efforts are continuing to assure that our system will be on the forefront of computer science. We have increased the variety, quality, and sophistication of the services we offer. Perhaps the most impor- tant single development is the first truly new version of BASIC in many years, which will be available during 1980. Developed under the leadership of Professor Stephen Garland, it will retain the simplicity of all versions of BASIC and yet provide considerable new sophistication that is consistent with modern programming theory. We have also improved our capabilities for the social sciences by adopting into our system a variety of packages for the handling of statistical and economic analyses.

As the capabilities of our system increase and as our users become ever more sophisticated and grow in numbers, we have had to face up to the danger that the demand for computing was growing too rapidly for us to keep up with. It has been a matter of great pride to us that computing was available freely to all those who needed it, just as our library would never dream of charging a Dartmouth user for borrowing a book. It was therefore with great reluctance that I pushed for putting a limit on the amount of com- puting that would be freely available for Dartmouth users. We have instituted a system of limits by categories of users, and are forcing those who exceed these limits either to raise the necessary funds to pay for the excess usage or at least to receive special per- mission to justify very heavy use. We placed these limits suf- ficiently high so that more than 90 per cent of all users will never become aware of them, and the system of controls seems to be working very well. Our largest users have become much more cost-conscious as a result of the limits we have placed on them, and it is my hope that this will delay by some period of years the necessity for the next major upgrading of the system.

Modern technology is helping us make improvements in the system at extremely modest cost. This is the age of mini- computers. These modestly priced, special-purpose devices are ideally suited to meet certain kinds of needs that would place an undue load on our large time-sharing system and can be met much more inexpensively with a mini-computer. Perhaps the most exciting use of such a device has been by Professor Jon Appleton of the Music Department in a project that has received nationwide publicity. His music synthesizer is both a device for the creative musician and ideally suited for the teaching of music. Two of our other uses of mini-computers have been to con- trol scientific equipment in laboratories and provide high-speed raw computation for researchers who may need millions of calculations in their research but do not need the variety of ser- vices of the time-sharing system.

In an age of the steady-state university, when very few new programs can be funded, the faculty voted high priority for two new programs in computer science. First of all, we have im- plemented an undergraduate major in this field that now attracts a large number of liberal-arts students, a field that is intellectually challenging and one that opens the door to a wide variety of jobs. Secondly, with the help of a generous gift from 1.8.M., we are about to launch a professional master of science program in com- puter science. This application-oriented program will give us an opportunity to train future leaders of computer science for in- dustry as well as academia and carry the Dartmouth philosophy in computing to a wide variety of applications. While an initial outside grant was necessary to meet the start-up costs, our hope is to make this program self-financing in the long run.

While the fame of our computing system does not yet equal that of Winter Carnival or those other features that everyone knows about Dartmouth College, it is increasingly true that when people talk about the College, its outstanding computing system is one of the things to be mentioned. I will never forget the excited letter I received from an undergraduate student who was traveling in India. Wearing a Dartmouth T-shirt, he visited a college on the Indian sub-continent. There he was approached by a faculty member who pointed to his shirt and said: "Dartmouth College —isn't that where they invented BASIC?"

f J s I re-read my remarks of five years ago, it is hard to see how I can add anything to what I described L. as the enormous significance of Hopkins Center in the life of the College. Yet, the number and variety of events and their impact have continued to grow.

Perhaps the greatest growth has been in the variety and quality of musical programs available at the Hop. Ranging from small "private" performances to enormous public events in Thompson Arena, and such outdoor events as Celebration Northeast on the Green, the richness of musical experience in Hanover is truly astounding for a small, rural town.

A happy outgrowth has been the attraction of a number of musically talented students to the undergraduate body. Because of the breadth of musical teaching ability within and beyond the Dartmouth faculty, individual instruction is now available to these gifted students. We are increasingly finding students who in another age wouid have opted for a conservatory of music now choosing Dartmouth as a happy combination of being able to continue their musical development and at the same time acquire a broad liberal education.

Equally significant are the variety and quality of dramatic per- formances and of exhibitions in the visual arts. The Hop has truly become the cultural center for northern New England. The Friends of Hopkins Center is an organization now numbering nearly 2,000 members, most of them not connected with the College. They represent a large portion of the states of New Hampshire and Vermont, and their generous support gives tan- gible evidence of the importance of the Hop to our region. Indeed, I have met a number of families who have told me that one of the major reasons they settled in or near Hanover was the availability of this magnificent cultural center.

With success come problems. There are ever-rising expec- tations about Hopkins Center. I know that its very able director, Peter Smith, has ambitious plans that could carry the Hop to even greater heights, and yet in an age of fiscal problems and in steady state, it is simply not possible to divert a larger fraction of the institution's budget to the arts. We must look to the thousands to whom Hopkins Center has meant so much to help it achieve its full potential.

A second problem, which I noted five years ago, is that Hopkins Center is running out of space. This is recognized in the Campaign for Dartmouth by making an art gallery and expan- sion of space a very high priority item. We are eagerly looking forward to the construction of the Harvey Hood Museum, which will for the first time provide an art gallery worthy of the College's collection and provide badly needed teaching space for the visual arts. At the same time we hope through ingenious renovation to provide relief for many of the now-overcrowded activities.

It is the Hopkins Center about which I can most truly say that for those who have experienced the splendor and variety of its programs, no description from me is necessary; for those who have never experienced these things, my verbal description will prove hopelessly inadequate in conveying just how much Hopkins Center means to the College.

IJ B hile Dartmouth College has been a pioneer in Br Br the use of computers in instruction, until five V V years ago it lagged behind in the use of other technological aids to instruction. The Office of Instructional Ser- vices and Educational Research (OISER) was made possible by two major grants from the Sloan Foundation and project grants from the Lilly Endowment and the Exxon Education Foundation. It provides professional support for the development and use of technological aids to instruction, aids to faculty in educational research, and evaluation of the effectiveness of instruction.

Thanks to the existence of OISER there has been a significant increase in the past half decade in the classroom use of television, videotape, instructional films, and slides. For example, the in- dividual viewing facilities available in Webster Hall are now used by some 2,000 students a year. There is considerable testimony from faculty and students that numerous courses have been made much more interesting and enjoyable and, hence, probably more effective than they had been before.

From almost non-existent television resources we have grown to the point where there is an extensive campus distribution system for TV, with reasonably sophisticated production capabilities. The distribution system now reaches 67 classrooms and special rooms, and it has the dual capability of sending televi- sion signals and receiving them from the classroom end. The capability of producing color camera work, a variety of graphics displays, and portable facilities for field work have made the medium much more flexible on the Dartmouth campus.

Particularly important opportunities exist in marrying the tele- communications capabilities of OISER with the flexible capabilities of our computer center. Some applications that would have been inconceivable a decade ago have now become feasible and financially affordable thanks to the existence of microcomputers.

The production of instructional materials, particularly video- tapes, has grown enormously on campus. Major uses have been made in the teaching of language, speech, government, and even crystallography. We are also more frequently recording impor- tant lectures and special colloquia for later use. The video capabilities are also used by administrative officers for personnel training.

The educational research arm of this office is of increasing use to academic departments, faculty committees, and administrative officers. OISER facilitates the analysis of student course evaluations and provides consultation in the design and evalua- tion of new courses. It also maintains a comprehensive data bank on which all faculty members can draw in their planning efforts. Professor William Smith, the director of OISER, feels that his office is still some five to ten years away from achieving its full potential. While some extremely important experimentation has taken place, it takes considerable time for faculty members to become comfortable with the new instructional tools. We are also lacking hard data in evaluating the effectiveness of various ex- periments.

Perhaps the greatest potential at Dartmouth lies in coordi- nating the needs and offerings of the four academic centers. There are few institutions as small as ours that have such outstanding centers, and we have a better chance for effective coordination than would be the case at a huge university. Provost Leonard Rieser '44 has the achievement of coordinated planning and mutual support by the center's as a very high priority item for the future.

James Cox, specialist in Twain, Hawthorne, and Melville.

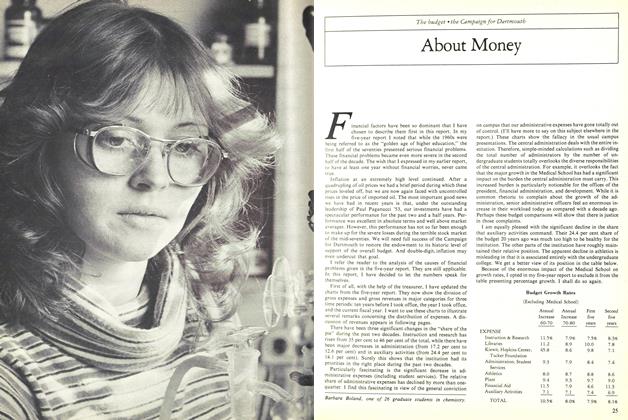

Art-urban studies major Josiah Stevenson 'BO sculpting in wood.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Feature

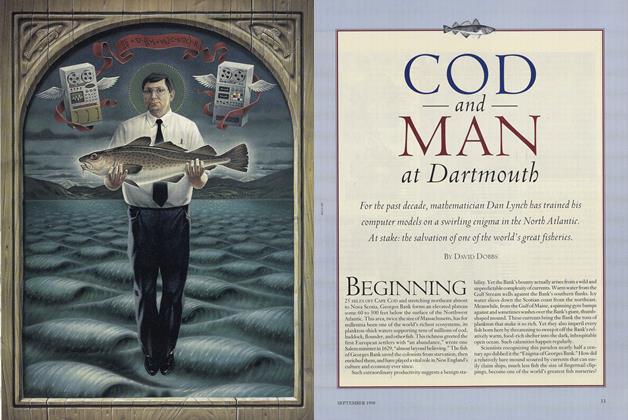

FeatureCOD and MAN at Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1998 By David Dobbs -

Features

FeaturesRising Star

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureSnowmaking at the Dartmouth Skiway: Taking the Wonder Out of Winter

DECEMBER • 1986 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Innovative Economist

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By MIKE SWIFT -

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52