The Medical School • Tuck School •Thayer School

"If the financial problems can be solved, the future of the Medical School looks very bright. But the next few years present a major challenge to the Dartmouth Medical School." This was my prediction five years ago.

Very significant progress has been made at the Medical School in the last five years. Yet this entire period was dominated by financial.problems. For the first time in a decade I am confident that the solution of these problems is at hand and that the future of the Medical School has been assured.

Five years ago I reported the launching of "an intensive but selective fund drive." Unfortunately, that approach was not successful. In retrospect the reasons are fairly clear. The Medical School did not have a natural alumni constituency. The pre-1974 alumni had all received their M.D. at another institution. Most of them also were Dartmouth graduates, and they tended to contribute to their undergraduate institution (usually Dart- mouth) and to their M.D. institution but not to the Dartmouth Medical School. With class size no greater than 24 during the entire period, the total number of living alumni was not very great. Nor was there a natural group to whom a regional appeal could be made. In metropolitan areas medical schools receive substantial gifts from wealthy patients and from corporations who wish to maintain the quality of health care near their major offices, but Hanover, New Hampshire, does not provide these constituencies. While eventually some significant gifts were ob- tained from individuals not previously connected with the College or the Medical School, this took an extended period of cultiva- tion. Dartmouth traditionally is not geared up for an intensive solicitation effort except during a major fund drive, and the Medical School fund drive did not gain momentum until the Campaign for Dartmouth was launched in 1977.

Several important developments had to take place before it was possible to solve the fiscal problems of the Medical School. Five years ago I reported on the beginnings of a medical center structure. Significant progress has been made since that time in developing the Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center into a true academic center. These developments have contributed in an important way both to the quality of clinical education and to the quality of health care. While on paper we are still a loosely knit organization con- sisting of four legally indepen- dent entities the Dartmouth Medical School, the Mary Hitch- cock Memorial Hospital, the Hitchcock Clinic, and the Vet- erans Administration Hospital in White River Junction we have made great strides toward joint planning and coordination of our efforts.

The Joint Council, which con- sists of trustee-level representa- tives and the senior executive officers of the four institutions, has proved itself an important tool for long-range planning and for the resolution of conflicts. Equally important, the chief ex- ecutive officers of the four institutions have been developing a tradition of working together toward a common goal. Perhaps the most important development has been the evolution of the role of the chairmen of clinical departments. Each chairman has now been designated as a medical center-wide officer with com- plete jurisdiction over both academic and service responsibilities. For many purposes it is now unimportant as to who the actual paymaster is for a given clinician. All clinical faculty members are members of the Dartmouth Medical School faculty. Those paid by the Medical School often perform a significant amount of health care services in addition to their academic responsi- bilities, and clinicians paid by the Hitchcock Clinic or the V.A. may engage in important teaching and research. While the chairmen must still obtain their funds from several different sources (a process we are trying to simplify), each is in a position to present a unified plan for the entire department and make long-range plans for developing the departments, well balanced between the needs of health care, teaching, and research.

A number of important successes would not have been possible without effective cooperation. I shall mention only the two most important ones. We were successful in attracting to Hanover one of the regional cancer centers, the Norris Cotton Center. With the help of federal funds, we now have the facility and the exper- tise for first-rate research and health care related to cancer. The other major achievement is the increasing success of our program of regionalization. This involves a cooperative arrangement with a number of other hospitals and small clinics from which the en- tire region profits. The Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center provides specialized services not available elsewhere and provides consultation and continuing education for physicians in the region. In turn, these affiliations help to insure the patient base necessary to maintain a first-rate, tertiary-care hospital and to provide additional locations for medical students to receive their clinical instruction. The overall result in the long run should be the best possible health care much better than normally available in a rural area at the minimum possible cost, by removing duplications of effort and facilities and providing health care wherever it can be most conveniently and most economically administered.

Special thanks should go to Professor John Hennessey, presi- dent of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital board of trustees, and Dr. Richard Cardozo '42, president of the Hitchcock Clinic. Each of them has played a major leadership role in bringing us closer to a truly unified center. Thanks must also go to Mr. William Yasinsky, director of the V.A. Hospital. The relations of the Medical School with the V.A. Hospital have been ideal.

The Medical School had to make a very difficult decision con- cerning its curriculum. It was one of the schools that pioneered with a three-year (as opposed to a four-year) medical curriculum. Given the very high cost of a medical education, it seemed attrac- tive to try to condense the training period to three years so that students could start earning money sooner and start repaying their debts! In effect, the Medical School went on year-round operation before the College did, but in a quite different way. Medical School students were attending classes almost con- tinuously over a three-year period. For the very best students the system worked well, but there were serious problems with students who found some of the courses difficult and with students who had any kind of health problem during their medical training. There was almost no opportunity for catching up, and the student who fell behind in effect had to take an extra year. There were also problems with the taking of medical board exams and applications for internships. The former were typically taken before the student completed his or her basic science training, and applications for internships had to be filed before a student had a chance to explore most of the clinical specialties. After a long and careful study the faculty concluded that the disadvantages of the three-year program outweighed its advantages. Starting this fall, the M.D. curriculum will be the more traditional four-year program.

During the past five years the Board of Overseers of the Medical School has come into its own. It has become one of the most active and influential boards at the College. Composed of distinguished physicians (both alumni and non-alumni), alumni members with a special interest in the Medical School, and representatives of the other medical-center constituencies, the overseers have played an increasingly active role in advising the dean and in making recommendations to the Dartmouth Board of Trustees.

In spite of all this progress, for several years the financial posi- tion of the Medical School appeared precarious. In my five-year report, I projected the need for additional revenues of $1.5 million per year. Since then, through very tight budget control, the deficit at its worst was under $1.4 million and has been declin- ing. However, with the lateness of the fund drive the Medical School was forced to use up all its reserves. A task force was set up to explore steps that could be taken, in addition to the fund drive, to solve the financial problems of the school. Three dis- tinguished members of the Medical School faculty, Drs. Robert Crichlow, the chairman, Marsh Tenney '44, and Henry Harbury, toiled for many months to produce what would prove to be a decisively important document for the school. Among their recommendations, the most important were: 1) change to a four- year curriculum, 2) an expansion of the enrollment in the first two years without an increase in the size of the faculty, and 3) renegotiation of the financial arrangements with the service units (the hospital and clinic).

While the change to the four-year curriculum was made primarily for academic reasons, it also brought some financial advantages to the institution. The ratio of faculty to students in the basic-science years was one the Medical School could not af- ford to maintain. The obvious solution would have been a reduc- tion in the number of faculty members, but we are already one of the smallest medical schools in the country, and there was a serious danger that a reduction in the size of the faculty would drop us below the critical level for a first-rate institution. The Crichlow Committee recommended that the same faculty teach a larger number of students. The target figure eventually arrived at was an increase from 64 students per class to 90 students. The dif- ficulty in implementing this recommendation, as the committee well recognized, was that the patient base was not sufficiently high to support teaching a larger number of students during the last two clinical years. The solution was affiliation with an ad- ditional teaching hospital, which necessarily would have to be at some distance from Hanover.

After two false starts, we discovered an ideal partner. Brown University had fairly recently developed an M.D. program, roughly the same size as that of Dartmouth, which grew out of a strong undergraduate science program. They were blessed with a wealth of clinical facilities but had no opportunity to expand teaching in the first two years. Their problem was the exact reverse of ours. We have successfully negotiated an agreement under which 20 students per year will receive the first two years of medical education at Dartmouth and the last two years at Brown. It is an arrangement beneficial to both institutions, potentially leading to a number of cooperative endeavors between two fine medical schools. When the program is fully in operation, Dart- mouth will be receiving 40 extra tuitions without any significant increase in expenses.

The necessity of renegotiating arrangements with the service units is a direct consequence of the unusual history of this particu- ular academic medical center. After the Medical School stopped granting degrees early in this century and with the subsequent creation of the Hitchcock Clinic, arrangements developed that are different from those of other academic medical centers. The normal arrangement is that a hospital carries most of the cost of the house staff, the interns, and residents. It is also customary that physicians who have faculty privileges but are not on the payroll of the medical school contribute a small portion of their time toward the teaching of medical students without compen- sation. In Hanover, the Hitchcock Clinic carries a significant portion of the cost of residents and charges for the teaching per- formed by clinic members. This led to complicated three-way negotiations as to whether the hospital could assume (as it legally can and as is done at most other institutions) a larger portion of the house-staff cost, in exchange for which the Medical School would no longer have to reimburse members of the Hitchcock Clinic for their teaching. While some of the details of the long- range solutions still need to be worked out, the negotiations have gone sufficiently far to result in an annual reduction of $500,000 in the net budget of the Medical School.

The combination of the success of the Campaign for Dart- mouth, the renegotiation with the service units, the four-year curriculum, and the agreement with Brown have had a dramatic impact on the finances of the school. We project a deficit of less than $400,000 for next year and a balanced budget by the time all of these plans are fully operational.

The trustees of the College showed enormous courage when, at the gloomiest period in the financial crisis of the Medical School, they guaranteed the existence of the school until the end of the Campaign for Dartmouth. Their trust that the problems would be solved has been fully justified by the developments since then. It would have been tragic if the Dartmouth Medical School had failed. Besides losing the fourth oldest medical school in the country, a school with many distinguished graduates, the impact on health care for the entire region would have been catastrophic. An academic medical center can provide health care of much higher quality than a hospital not affiliated with a medical school. This is reflected in the wealth of specialties that are represented on the staff and in the ability to attract physicians of the very highest quality. One of the great attractions bringing in- dividuals to the College, whether they be faculty, administrative officers, or students, is the beautiful, rural location. This location would not be nearly so attractive without the existence of first- rate health care. We are now fortunate to have one of the few truly rural areas that can provide health care of the highest quality. If the Campaign for Dartmouth reaches its successful conclusion, we will have assured the future of the Dartmouth Medical School. This will have enormous impact in the long run for the region we live in and for the quality of Dartmouth College as a whole.

Special tribute must go to Dr. James Strickler '5O, who has now served as dean of the Medical School during seven years of a critical period. Without his unfailing loyalty and belief in the school and his untiring efforts, none of the above achievements would have been possible.

T m he past five years have been a period of soul-search- B ing for Tuck School. The school has continued to prosper in terms of both the quality of its students and its significantly improved finances. As a result, there was ex- tensive discussion as to what the future plans of the school should be. This process involved lengthy faculty discussions, a review by a distinguished outside visiting committee, discussions with the school's board of overseers and with the Dartmouth Board of Trustees. A course has been charted for the future involving modest expansion over the next decade, with the focus on im- proving the quality, breadth, and depth of the faculty.

The past five years have seen major changes in the personnel of the school. Six new tenure appointments have been made, one of which for the first time in the history of the school went to a candidate outside Tuck School. Recruitment of new faculty has focused on building on existing strengths and on broadening the areas of competence of the Tuck faculty. The long discussions have convinced all of us, however, that the size of Tuck's faculty is somewhat below the critical level. An increase to about 30 regular faculty members is desirable. This need for increase reflects the growth in complexity and sophistication of management-training schools. The decision has also been made that Tuck is better off continuing its traditional M.B.A. program for which it has a strong national reputation than adding a doctoral program to its offerings. Today, Tuck is totally self, supporting and in sufficiently strong condition to be able to sup- port a modest increase in the size of the faculty. The remainder of the faculty expansion will be achieved by a very small increase in the student body. Fortunately, the addition of Murdough Center has broadened the facilities of Tuck to the point where it can sup- port the planned increase.

On the curricular side, the school has strengthened its offerings in operations and production management. It also plans to add courses in the area of public policy. The school does not intend to offer a degree program primarily for those who wish to pursue a career in the public sector; instead, there will be increased curricular offerings dealing with the role of government in shap- ing the environment within which business firms operate.

The number of applicants to Tuck School has grown from 1,400 to 2,000, and this has led to marked improvement in the overall quality of the student body. The trend for students to ac- quire work experience before going to a graduate business school has continued. Today, more than two-thirds of the entering students at Tuck School will have had such experience. There has also been a steady increase in women applicants for the M.B.A. degree, and an entering class today will have nearly one-quarter women members. Tuck School has also made a very active effort to recruit minority applicants, but the school has not yet seen the fruits of this effort.

Perhaps the most spectacular success has been in the Tuck Ex- ecutive Program. It is well established as one of the leading programs of its type in the nation. It was described by the New York Times as ". . . one of the few new entrants to break into the upper echelon." The program has been so successful that starting last summer two sections had to be offered. In addition the school has participated in a variety of other continuing education programs. These programs play an important role in building bridges between Tuck's academic environment and the business world. They also contribute significantly to the financial stability of the institution.

Tuck continues to have phenomenal success with its placement program. This year more than 200 companies made visits to our campus to recruit the 130 M.B.A. candidates. Starting salaries continue to rise every year, including each year a few truly phenomenal offers.

The financial strength of the institution results from a com- bination of factors. Its students are financed mostly through a loan program, which they can well afford to repay out of high salaries. A continuing-education program makes a significant contribution. Corporate gifts have continued to come in at a very healthy level, and the Tuck Annual Giving Program is one of the strongest in the nation. With a participation rate of more than 40 per cent it is anticipated that this year's annual fund will total over $300,000.

It is clear that Tuck School is one segment of the institution that has not been significantly affected by adverse outside con- ditions. Instead, throughout the decade, Tuck has grown m quality, in stature, and in financial stability.

77 ive years ago I said: "For the past two years Dean m Carl Long has provided much needed stability for the uK. school. He has formulated plans that will e additional impetus to Thayer by striking out into new fields, in- cluding the education of non-engineering, undergraduate students. He is also working hard to strengthen the financia foundations of the school." Dean Long has continued to provide outstanding leadership, and the successful completion of all his original plans is now within sight.

A key to the success of Thayer School has been a conscious decision to be strong in a small number of areas, rather than splintering limited resources among all possible engineering specialties. The strengths of the school lie in five major areas two traditional ones and three very modern areas. There is strength in electrical engineering, with special emphasis on elec- tronic design, digital design, computer technology, and elec- tromagnetic theory. In mechanical engineering the emphasis is on fluid and thermal sciences and mechanical design. One of the most fascinating new fields in which Thayer School is pioneering is biomedical engineering. In a very successful joint program with the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, the engineering school is making a significant impact on the application of modern technology to health care. The fourth area of specializa- tion is environmental engineering (policy planning for natural resources). Finally, in cooperation with the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is located in Hanover, a program is being developed in cold regions science and engineering.

A tangible measure of the growing national recognition of Thayer School is that externally funded research has been grow- ing at the spectacular rate of 25 per cent per year. It is also reflected in a significant increase in faculty publications and in the quality and productivity of the school's graduate students.

One of Dean Long's major goals was to have faculty and ad- vanced students heavily involved with real-life problems. To this purpose two years ago the school established a center for engineering design, called INVENTE. The goal is to teach engineering through its practice. This organization has es- tablished a strong tie with several major corporations and provides an opportunity for interaction between faculty and students and industry on current and important problems.

The school has been equally successful in expanding its impact on undergraduate education. The number of engineering science majors has more than doubled in the past half-decade. Engineer- ing science is now the seventh largest major in the College. Thayer School is also expanding its commitment to the teaching of non-engineering students. An ambitious program is being planned to acquaint non-science students with the importance of modern technology and with the ethical and social problems created by technology. I am convinced that the successful com- pletion of these plans will significantly enrich our liberal-arts education.

The single most spectacular achievement of the school is the demonstration that a considerable strengthening of research and education can have a highly positive impact on the fiscal health of the institution. Ten years ago Thayer's financial situation was ex- tremely shaky, and it was heavily dependent on subsidies from the central College. The progress of the past few years leads us to hope that by the end of the Campaign for Dartmouth, Thayer School will be stronger than ever and totally self-supporting.

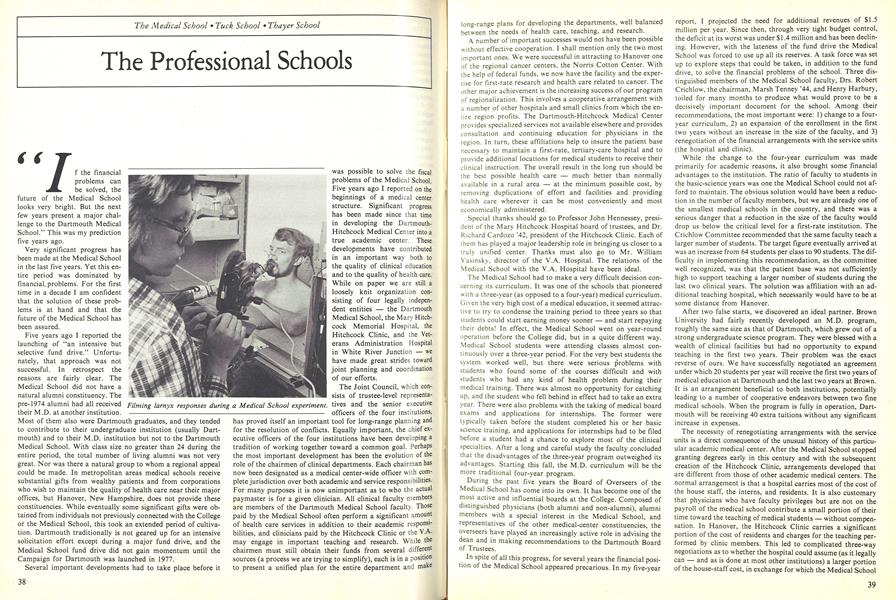

Filming larnyx responses during a Medical School experiment.

Professor Horst Richter at Thayer's steam water-spray tests.

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryWalter F. Wanger 1915

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureDemocracy's Influence on University Education

January 1960 By BERTRAND RUSSELL -

Feature

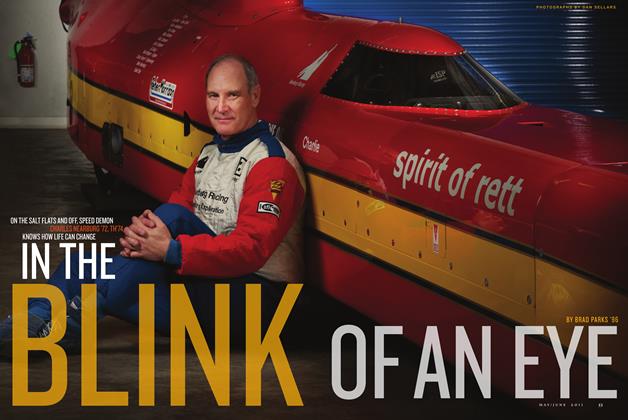

FeatureIn the Blink of an Eye

May/June 2011 By BRAD PARKS '96 -

Feature

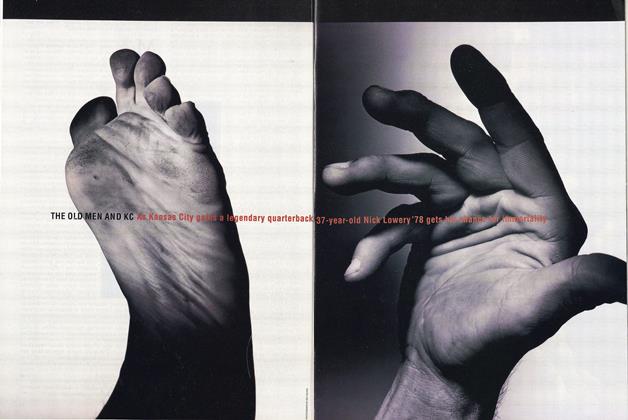

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

NOVEMBER 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureThe Teacher of Social Science and the World Crisis

February 1954 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS -

Feature

FeatureThe Humanistic Pursuit of Values

MAY 1967 By ROBIN J. SCROGGS