Federal regulations • affirmative action • business administration • the trustees

It is very hard for anyone who has not participated in an academic administration in the 1970s to appreciate the enormous increase in the complexity of running a college. That increasing complexity is due to a number of different developments.

The single greatest factor is the much more intrusive role of the federal government. It has gen- erated mountains of paperwork, endless regulations (usually not very clear), and it has resulted in large numbers of federal teams descending on campuses to check compliance with various regula- tions. It is commonly assumed that this is the direct outgrowth of federal support, but there is no correlation between support and intrusion. There has been only one area where we have been sig- nificantly helped by increased federal aid: financial aid to undergraduate students. In other areas we have at best held our own, and in constant dollars we have usually lost ground. We still rely on federal aid much less than our best-known sister institutions, but the paperwork has come nevertheless. Nor is it true that if we gave up all federal aid, which would have a disastrous impact on the institution, we would be exempt from all this paperwork. Many of the regula- tions are tied to human rights, not to federal aid.

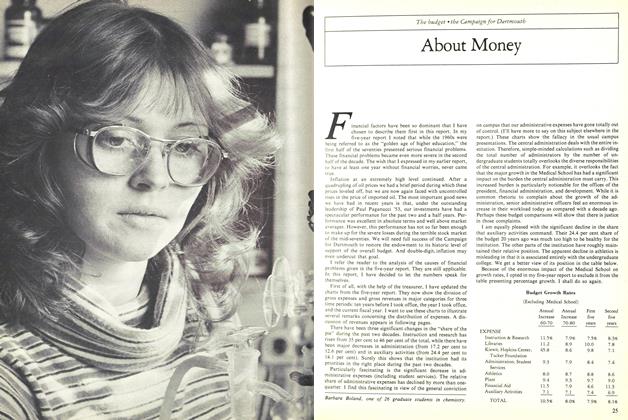

Secondly, the financial adversities of the 1970s have signifi- cantly increased the load on all of us. A distinguished trustee emeritus has told me that, during his years as chairman of the budget committee, they had never finished without a surplus, and the minimum surplus he experienced was a figure that in 1980 dollars would be about 5100,000. I admire that record and envy it. Although I am sure that achievement required extremely careful management, I must believe that it takes significantly less effort to decide how much of a surplus to put into reserves and how much to spend on new programs than it does to cut several hundred thousand dollars out of the budget. Besides the annual battle of meeting the trustee guidelines, we are currently going through the third round of major budget cuts. Such a pro- cess is, of course, very painful. It is also extremely time-con- suming. That it occurs at a time when all constituencies feel they should have much more signifi- cant voice in the decision- making, makes the process even more burdensome.

The third major factor is that we live in an age when everyone is either suing someone else or threatening to sue. Academic institutions are particularly vul- nerable to the threat of law suits. Even if the institution wins all or most of these cases, it can run up enormous legal fees and admin- istrative expenses in the process. We have been fortunate in having many fewer such cases than our sister institutions, yet the burden is quite noticeable. Most of these cases are not one-against-one confrontations, and an agency of the federal government is likely to play a major role. These days anyone who has any serious com- plaint founded or unfounded can find an appropriate fed- eral regulation under which the individual can bring the full power of the federal government to bear dn the institution.

Ten years ago the College had no full-time lawyer. We had a vice president, the late John Meek '33, who had legal training and either did the work himself or hired outside counsel. Today we also have a vice president who is a lawyer, Paul Paganucci '53, but he has two full-time lawyers on his staff and must in addition spend much more on outside legal fees. This is due in part to what I have just mentioned, in part to the necessity of monitoring an enormous number of regulations by federal, state, and local governments, and in part to the complexity of today's fund- raising. We are delighted that many gifts are coming in in the form of real estate, one form of investment that still shows enor- mous capital appreciation. The disposal of a piece of real proper- ty, however, is vastly more complex than the selling of stocks. It is little comfort to know that most of our sister institutions are spending proportionately much larger sums on legal expenses. It is one more example of extra expenditures that we would much rather use in direct support of education being forced on the in- stitution.

In this connection I cannot resist the temptation of citing here a quote from the 1773 census of Grafton County, New Hampshire, sent to me by a Dartmouth alumnus who happens to be a lawyer: "We have a county of over 3,000 square miles, a population of 6,- 549 souls, of which 90 are students at Dartmouth College and 20 are slaves. We have 25 incorporated towns, all in thriving condi- tion, including 14 grist mills, 5 saddler shops, 7 millwrights, 8 physicians, 17 clergymen, and not a single lawyer. For this happy state of affairs, we take no credit unto ourselves, but render all the glory to God."

Whenever there is a budget crunch, it is a favorite pastime to blame our financial difficulties on the growth of the administra- tion. While my foregoing comments explain why some increase was inevitable, I would like to give a more detailed account of what growth has taken place and where it occurred.

In my previous report, I explained the growth due to the imple- mentation of coeducation, year-round operation, and the resulting expansion of the student body. I would now like to describe the changes in the seven-year period since 1972-73.

It will be instructive to look at one vice presidential area of responsibility in depth. The largest number of administrative of- ficers roughly 100 report to the dean of the College. It must be remembered that since the reorganization of student affairs, he has reporting to him not just all the traditional services dealing with students but also the Admissions Office and all of athletics. Therefore, there is a tendency to single out the dean whenever growth of administrative officers is the popular topic for discus- sion.

A careful examination of the facts shows that in that seven-year period there has been a net increase of eight officers in Dean Manuel's various areas of responsibility. We have added seven women coaches additions that were necessary to implement women's sports and are required by Title IX. One of the weakest areas of student services was graduate-school and career counsel- ing, and there we have increased the number of officers by two. Given the tight job market and the increasing competition for places in professional schools, this was an extremely important investment by the College. The work of the Fina'ncial Aid Office has become vastly more complex due to the variety and complex- ity of federal financial-aid programs. As indicated above, while the complexity has increased, this is one area where we have also received substantial additional aid from the federal government in the form of scholarships and loans. Two financial-aid officers have been added, with the help of fees we receive from the federal government for administration of federal programs. We have also added one admissions officer to coordinate minority recruitment. The faculty voted a program of reading and study skill. This program has been widely praised on campus, but it has resulted in the addition of two officers. When we opened the Collis College Center, it was necessary, of course, to recruit a director for the center. Finally, two of the apparent increases were reclassification of jobs from staff to officer status.

The total of the above-listed increases is 17. Since the net in- crease was only eight, we must conclude that there has been a reduction of nine officers in other areas. In addition, Dean Manuel s responsibilities now include those previously carried by V ice President Ruth Adams's office. Therefore, the net figure masks significant cuts and improvements in efficiency achieved by Dean Manuel.

Looking at the rest of the institution, my best estimate is that there has been a paper increase of 18 officers. I say that this is a "paper increase" because ten of these consisted either of changes in status from staff to officer or recognition that individuals classified as full-time faculty members were really part-of-the- time administrators. The real net change is only eight (rather than 18), and five of these occurred within the associated schools. The remaining net change of three is a combination of many necessary additions and offsetting cuts and cost-savings.

As we go through one more cycle of major budget cuts, we will necessarily reduce the number of administrative officers. Since it is my belief that the increases we experienced in the past decade were barely sufficient to respond to the growth in the size of the institution and the increase in complexity, I worry that we will end up being dangerously thin in a number of years.

T1 m he past five years have seen great progress in Dart- K mouth College's affirmative-action program. We are greatly handicapped in those areas where we draw on the local labor force, but we have done spectacularly well in the national market.

Our strongest efforts have been for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and for administrative officers. A decade ago the Faculty of Arts and Sciences had six women faculty members of whom one had tenure (she has since retired). Today there are 56 women among the regular ranks in the faculty. This represents 19 per cent of the total, which is higher than that at any of the in- stitutions with which we compare ourselves! Given the late entry of Dartmouth into coeducation, this achievement is truly spec- tacular. The trustees had set a goal of having 25 per cent of new faculty appointments be women, and we actually achieved an average rate of 36 per cent well above the rate at which women are receiving Ph.D.'s.

Today nine of the women have tenure in Arts and Sciences. Even this very modest number puts us ahead of some of our sister institutions on a percentage basis. However, I am not at all satisfied with this number. Fortunately, a significant number of very strong candidates are coming along in the ranks of the assis- tant professors. My first reading of the relative strengths of can- didates comes during the third and fourth year when they are up for reappointment and are applying for faculty fellowships. It is clear to all of us who have reviewed these candidates that we are certain to have a spectacular increase in the number of tenured women within the next three years. By 1984, we should have pre- sent on the faculty a significant number of tenured women. This will both add to the balance of our curriculum and provide role models for women students.

We have also exceeded our goal of 10 per cent of the new ap- pointments being minority persons. The total number of minority faculty members in the regular ranks has grown from seven to 25, and of these nine are tenured. Given the geographic location of the College, that is a truly remarkable achievement.

The one unrealistic goal we set was that 50 per cent of new ap- pointments of administrative officers should be women. We fell below this level, but today more than 28 per cent of all ad- ministrative officers are women. Since we are only eight years into coeducation, however, I take considerable pride in that achievement. Although the heaviest representation of women ad- ministrative officers is in middle management where there is a considerable turnover, we also have made progress in the more senior ranks. Today there are eight women in officer grades 6-8 (just below the vice presidential level).

The number of minority administrators has also grown from 1 per cent to 6 per cent, and we have one black administrator in each of grades 6, 7, and 8. For minorities we have exceeded the stated goal of 10 per cent of new appointments. We have also ex- perienced considerable turnover among minority administrators This is bound to be the case when one attracts extremely able minority administrators who can compete successfully for positions nationally and when there is a limit to the number of senior positions that become available. Several minority ad- ministrators who received their start at Dartmouth have gone on to distinguished careers elsewhere.

Margaret Bonz has proved herself to be an exceptionally able affirmative-action officer. Her endless energy, her competence, and her invariable cheerfulness have made a success of one of the most difficult positions in the institution. Her very small office (one and three-quarters officers) has responsibility for a wide variety of assignments. Under her leadership we received ap- proval of our Affirmative Action Plan in October of 1975 one of the earliest institutions to receive full approval. The plan was revised and updated in 1978. She has led us through reviews under a variety of federal regulations, such as Title IX (sex dis- crimination), Title VI (discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin), age discrimination, and facility modifications required for the handicapped. She also conducts regular compen- sation equity reviews, has been instrumental in our formulation of a maternity-leave policy, makes sure that all our positions are properly advertised, has set up several grievance procedures, and conducts many training programs for the officers and staff of the College.

If we keep up our intensive efforts in recruitment and in sup- port of candidates for promotion, five years from now Dartmouth College should have convincing proof that it has had a true com- mitment to the goals of affirmative action.

/n my five-year report I mentioned that Rodney Mor- gan '44 had taken over the new job of vice president for administration. Bringing 25 years of business experience with him, he methodically attacked the far-flung business activities of the College.

Few people have a full understanding of just how many different activities the College engages in. We own a hotel, a ski resort, a golf course; we provide housing for thousands of students and employees of the College, run a large dining hall, as well as several smaller, more intimate restaurants; we are ma- jority stock holders in the Hanover Water Company, and we have far-flung real estate holdings. In addition to this, there are all the normal business activities associated with an enterprise that has a gross budget in excess of $BO million. While the bottom line for Dartmouth College is the quality of the education that it provides and the quality of life on campus rather than profits, the more ef- ficiently its business activities are run the more money is available for the fundamental mission of the College. It is in this area that Vice President Morgan and a very able corps of officers report- ing to him have made significant contributions during the ex- tremely trying decade of the seventies.

The single greatest success story is that of the Hanover Inn. When Robert Merrow was appointed manager of the Hanover Inn in 1972, the Inn was running a very large deficit, thus divert- ing funds that should have been used for educational purposes. In four years he turned around the Inn's finances to a modest profit, with a total net improvement of over $250,000! He has successfully maintained that level of performance through the very difficult years of inflation and increasing competition in the region. At the same time, anyone who has recently visited the Inn will testify that the quality of the physical facilities, the food, an the service has never been higher. Indeed, Robert Merrow has demonstrated that people are willing to pay for high quality an that therefore high-quality service is good business. The outstand- ing performance of the Hanover Inn has been one of the very few pieces of financial good news that the College has had in the last half decade.

Rodney Morgan takes enormous pride in keeping down the cost of the operations that he supervises. He has almost com- pletely wiped out the deficits of our auxiliary activities. In areas where there are no offsetting revenues, gross expenses have grown at a significantly lower rate than inflation and slower than in other parts of the College. He also is continually on the lookout for improvements in efficiency which will help all budget centers.

For example, he was responsible for the installation of a com- puterized telephone system called "Ernestine," of which we have all become very fond. With our previous system of WATS lines, we often found intolerable waiting periods for an open line, and therefore secretaries would place calls through the more expen- sive direct-dial route. "Ernestine" will remember that you have placed a call and were unable to complete it and will call you back when there is an open line. This has cut down significantly on the by-passing of rented lines and has saved time and frustration for our secretarial staff. By placing all calls through the cheapest possible route, it has also realized additional savings in our telephone costs. Now we have in the discussion stage the next im- provement in our telephone system, which promises further savings as well as additional features of convenience made possi- ble by modern technology.

Perhaps less popular among the changes in business ad- ministration was the strengthening of the Central Purchasing Of- fice, but the lower costs achieved through insistence on obtaining comparative bids and using the leverage of the large volume of purchases the College makes has again resulted in savings for many different areas. It was not easy to sell the system. It is more convenient for a departmental purchasing officer just to pick up the phone and order a particular piece of equipment. While this may be more convenient, it is also, in most cases, more expensive. My only regret is that in spite of the demonstrated savings possi- ble through Central Purchasing, there are still too many purchasers who by-pass the system. This is an area in which we must improve compliance.

The most difficult area that our business administration has to deal with is the area of energy. Since the original quadrupling of the price of oil, oil prices after a period of stability have again doubled and they continue to increase. We have implemented a very ambitious program of energy saving. The buildings that were in existence ten years ago now use only 75 percent as much oil as they did then. As a matter in fact, in spite of the addition of five major buildings (Murdough, Vail, Fairchild, Thompson Arena, and Channing Cox), we use/CM oil today than we did in 1970. The total annual cost of oil has reached the staggering figure of $2 million, but we at least have the satisfaction that without our vigorous energy-saving program the cost would be $600,000 higher! This very important result was achieved through a variety of measures ranging from a sophisticated environmental-control system to the installation of energy-saving devices such as storm windows and to a continuing effort to make all of us more energy conscious. The only depressing fact is that we have now used up most of the options for saving energy, but oil prices continue to rise.

I went into considerable detail to describe the achievements of the business administrators because they are probably the least appreciated heroes on campus. It is a favorite game to complain when Buildings and Grounds sends a larger crew than necessary to make a repair or if an office is charged the full cost of some service they have requested. While no human system is perfect, it is important for everyone to realize that if it were not for the significant improvements made by Vice President Morgan, the million-dollar cuts that we face would be twice that large. He and his colleagues are already hard at work trying to identify further areas in which gains can be made without affecting the quality of the institution.

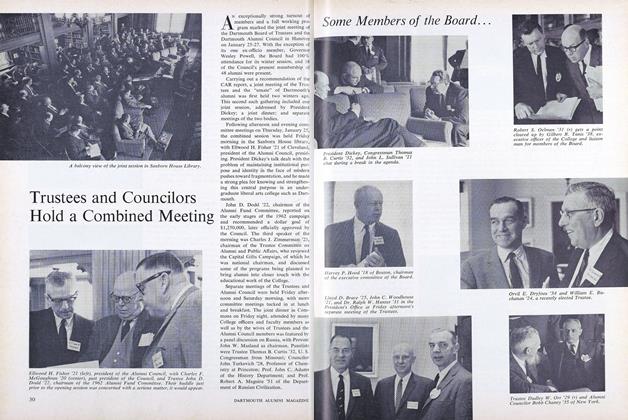

77 ew people have an understanding of how the Dart- M mouth Board of Trustees works and how great the JL- contributions of this body are to the College. One of the secrets of the success of our board is its small size. We have a membership of only 16, including the governor of New Hampshire and the president of the College.

A good measure of the increased complexity of the institution has been the growth in trustee business. I was once told by a long- time Trustee that 40 years ago the board would meet at 9:00 a.m. and conclude its business by noon. Today the board meets for two and a half days four times a year and has an additional summer retreat to permit in-depth discussion of a few major issues. In spite of the frequency and length of these meetings, the trustees' agendas more often than not are hopelessly jammed. This is true in spite of the fact that the Dartmouth board is very good at delegating responsibility. It does not interfere with the prerogatives of the president, the administration, or the faculty but limits its discussions to fundamental issues of policy. These issues have grown like mushrooms. Nor is the work of the trustees limited to the regular meetings. Several committees of the board have additional meetings, most notably the Investment Committee, which meets monthly. Trustees also serve in a variety of capacities as individuals. Of course, many of them play an all- important role in planning and carrying out the Campaign for Dartmouth. They serve as trustee representatives on the various boards of overseers and make a major effort to stay in touch with all the constituencies of the College.

Perhaps trustees do not receive the credit that they deserve because the only person who can truly judge their performance is the president of the College, and statements by him are suspect because his job depends upon the continued confidence of the board. Now that I can no longer be accused of having a reason to flatter the trustees, I feel that I must speak out. This institution owes an enormous debt to a small group of truly devoted and in- credibly hard-working individuals who have freely given of their time to the College that they love. It is sometimes a thankless job because their wise decisions are taken for granted, and when they have to make a controversial decision which is unavoidable for any board they receive criticism from several constituencies. In a very real sense the College would not be what it is today without the selfless service of this remarkable group of individuals.

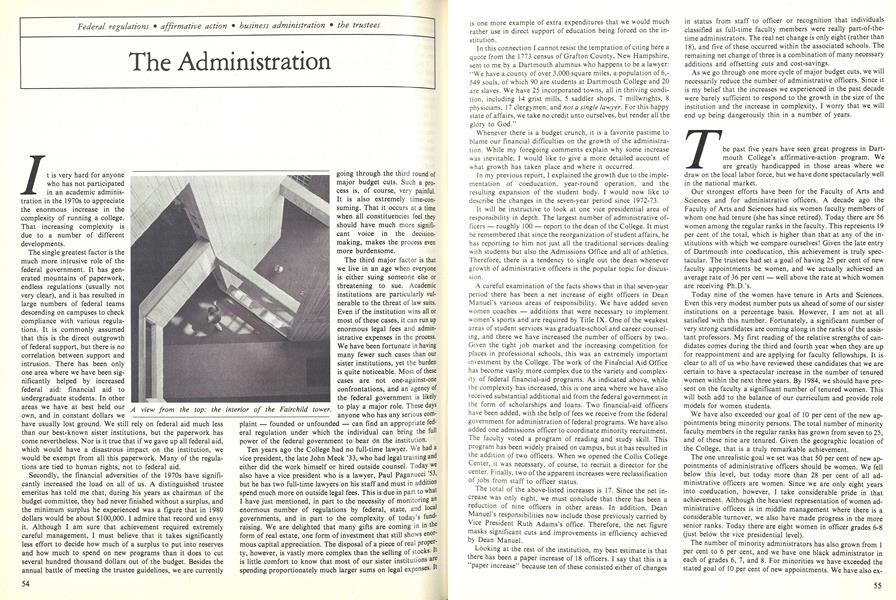

A view from the top: the interior of the Fairchild tower.

In the heating plant: the cold fact of $2 million for oil.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSome Members of the Board...

March 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLawrence Barcella '67

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAMPAIGN BUTTONS

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCorps Values

Jan/Feb 2008 By Julie Sloane ’99 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1958

July 1958 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1962

July 1962 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY