ONE hundred and ninety-eight commencements, but none like this. Alumni climbing onto their chairs, yelling, "Lynch him! Get him off! Get him out of here!" Parents and alumni standing up and storming off as if escaping a plague. A chorus of boos and catcalls, of cursing and hissing, rolled like a wave toward the podium. When the speaker finished, the members of the senior class, many wearing white armbands to protest the war, rose to their feet and applauded him. Exhausted, he returned to his seat. James Witten Newton, valedictorian of the class of 1968, trembled slightly as he surveyed the crowd. He had said what he had to say. He had attached his beliefs to his actions, his future to a precarious fate. Now what?

His Quaker fellows would say that on a sunny June day 13 years ago, Jamie Newton had "spoken Truth to Power." The degrees of truth and power are debatable, but the fact that Newton spoke his conscience is not. He told the gathering that the Vietnam war was "a colossal stupidity, an expensive lesson in the futility of modern aggressive imperialism." He urged their sons to refuse to serve, to "escape to a country of greater freedom in the north if necessary. In the warm sunlight reflecting off Baker Tower, he reminded the seniors of a "nightmare vision of smoking cities policed by soldiers, of silent factories, of empty stores."

"American society trembles," Newton warned, "before the threat that the cancerous injustices it has tolerated so long may now destroy it from within. ... We fool ourselves if we think that we can build our own society and destroy a foreign nation at the same time."

From 1771 to 1968, the valedictorians of Dartmouth College had either "supported or ignored all American wars," according to Professor Noel Perrin, who wrote about Newton and student protest in The NewYorker in July of 1968. Since 1968, no Dartmouth valedictorian has more than briefly touched on the topic of war. Newton's was a speech to remember then, a speech apart. "The alumni were kind of nonplussed," recalls Betty Eberhart, a Hanover resident who was at the commencement to watch her son Richard be graduated. "They couldn't believe that anybody could get up and say anything like that, right on the platform. That's not what they wanted to hear."

Thirteen years later, I heard about Newton's address from Professor of Government Frank Smallwood '51. He was recalling the many commencements he had attended, and remembered one speaker especially who "really shook things up. The name of that speaker, I later found out, was James Newton. I wondered what James Newton was doing, what had happened to him since the address, how a young man whose vision for the world was so different from most people's had survived. That was the overriding question in my mind as the person variously described as a "Vietnik, a "frightened little man," and a "sensitive young man'' opened the door of his suburban apartment in Menlo Park, California. What did I expect a fierce union organizer? A dreamy idealist? A stockbroker? A college professor? Whatever, here was James Newton, with a neat beard, alert, engaging eyes, an energetic air, and a wide-open laugh. If he indeed was, as one alumnus called him, a red bearded monster," then he was at least a cordial one.

IF you are not one of the 136 alumni whose letters cram an ALUMNI MAGAZINE file marked "Newton Valedictory Letters (July 1968 on)," or one of the thousands of alumni who followed what W. H. Ferry 32 called the "hot, sad, and confused debate" surrounding Newton's speech, then some history is in order. Jamie Newton begins that history in his hometown of Glendale, Arizona. He grew up as a Quaker among "Goldwater Republicans and pinto Democrats." At 12 years, he marched with his mother in a protest against nuclear missiles at Davis-Monthan Air Force base near Tucson. "We marched all morning in a pouring rain, while people drove alongside and threw rotten fruit at us." In eighth grade, Newton was awarded the American Legion Award for Outstanding Citizenship. In high school, he received the George Washington Honor Medal Award from the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge for "as they put it, 'helping to bring about a better understanding of the American way of life.' " At his high-school graduation Newton was salutatorian. In his address, he called for unilateral nuclear disarmament. "There was mild grumbling,'' he recalls.

He came to Dartmouth at the suggestion of a high-school teacher, an alumnus of the College. At Dartmouth, he came under the influence of two professors. In Jonathan Mirsky, then an assistant professor of Chinese, Newton found an example of a scholar, teacher, and activist with "real intellectual and personal integrity. Professor of Psychology Robert Kleck led Newton into the study of social psychology. In his senior year, Newton was an honor's psychology student preparing a thesis on nonverbal communication. Throughout his first three years, Newton followed Vietnam in the papers, as did many students, but felt uncomfortable arguing against the war on purely religious grounds. He thought of himself as committed but politically naive, lacking a "common frame of reference with which to discuss the war with others." He stayed out of most debates on the war.

However, when Newton returned home from a junior year in Spain to find his father terminally ill with cancer, he made a connection between his father's pain and the suffering of those half a world away that spurred his anger toward the war. "My father was in extreme pain," Newton told me, "and I think it is true to say that everything medical science knew to do for him was being done. He had the best that medical science could give. And as I stood there all that time with him suffering, I found myself thinking of people in Indochina who were with their beloved relatives, watching them suffer, suffering with them, who couldn't at least say it was through no fault of any person that their suffering had come about, and that everything that could be done to help was being done. Even worse, they were suffering for bad reasons. . . . I identified very closely with that suffering in a way that I had not before. During those three days, I made the decision that I would do whatever I could do to contribute to hastening the end of the war to get the United States out of Vietnam."

Newton returned to Dartmouth for his senior year, determined. Through the Hanover Friends Meeting, a local Quaker group, Newton met Donald Pease '66, and with Pease and others organized weekly peace vigils and a Dartmouth Peace Committee. (By March, Pease, a Phi Beta Kappa, would be on a plane to Canada to escape prison, the first Dartmouth student to flee north.) Newton devoured information on the history of the war, trying to attain a "solid intellectual justification" for his religious and emotional opposition to it. He would stay up until late at night arguing the war with his neighbor Bill Lind '69, then vice president of the Dartmouth Conservative Society. That summer, Newton returned home to organize a series of public dialogues on the war. He hoped to get more people to listen if the forums allowed a wide variety of viewpoints on the war, "expressed in an atmosphere of mutual respect."

In the spring of 1968, his father's illness worsened, and Newton returned to Glendale. Newton helped his mother and sister keep a 24-hour vigil over his father, whose condition remained stable, though critical, three weeks into Newton's spring term. There were courses Newton needed for his major which would not be repeated for a year, during which time he would lose his student deferment. Then, he would face the draft, resistance, possibly jail who knew? He and his father decided he should return to Dartmouth. He arrived in Hanover emotionally, physically, and mentally exhausted, wanting only to finish his thesis, traveling only between his room and the library, much less active in peace activities.

Two weeks before commencement, Dean Thaddeus Seymour asked Newton to deliver that year's valedictory address. Newton remembers reminding Seymour of the kind of issues that meant the most to him - specifically, the war in Vietnam - and told Seymour he would inevitably address these issues. Seymour, now president of Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, remembers telling Newton he believed the senior would confront the issues that most concerned the class of 1968. "I had no second thoughts," recalls Seymour. "Newton was universally liked, and he was not alone or unique as far as political opinions. We wanted someone who would speak to the senior class and to the times."

Newton's father had died 12 hours after his son left home. If his father's illness, and Newton's own desire to complete his undergraduate education, had once prevented Newton from engaging in protests which might land him in jail, these were no longer reasons: "Fate, in the person of Thaddeus Seymour, was saying to me, 'At the precise moment of your commencement, express your convictions as fully as you can, or acknowledge that it's all been a sham.' " Three days before graduation, Newton approached Seymour with a copy of the speech.

He offered Seymour a chance to find somebody else, somebody who could give a speech that wouldn't cost the College "some alumni love and money." Newton remembers Seymour saying he did not think a college should bridle free speech to protect its income.

If Seymour, who recalls with "sadness" the "shouting match" that hampered Newton's speech, didn't ask Newton to tone down the valedictory, many of Newton's friends and classmates did. Not only did they fear he would be arrested, but they also feared that, in the growing climate of political violence, their friend would be hurt. The night before commencement, Newton sat up late, thinking. A memory surfaced which would stay with him and give him the strength he needed: "A few days before my father's death," he recalls, "we talked a bit metaphorically about life and death. The way he put it, we had been traveling together for a long time and now had to go in different directions. We couldn't continue to walk along the same path, and we recognized that sometimes both of us were afraid. He didn't know what death would bring, and it was scary. And I looked ahead, and I didn't know what life would bring. We realized that we couldn't promise .each other not to be scared. What we could promise was that, scared or not, we would continue to walk along in the direction we felt our consciences led."

Newton was still thinking of that fatherson talk the next day, as he sat on the dais, waiting to deliver his speech. Soon, it would all be over, the message, he hoped, conveyed. That message is perhaps best summarized in these two paragraphs, extracted from the valedictory as printed in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE of July 1968:

"Men of the class of 1968, educated men, Dartmouth men, before you set off to participate in the devastation of that small country, Vietnam, and to risk your lives into the bargain, consider what you are about. . . .

"Men of the class of 1968, educated men, Dartmouth men, use the skills that you have gained here as you plan your courses of action. We must find our places in an ongoing universal struggle for freedom and dignity. I urge you to refuse to fight in Vietnam when that call comes to you. . . . The society we seek at home and the cooperative world we must have can come only through the commitment of our talents and our resources to the tasks of peaceful, constructive change. We must make that commitment our own."

After the uproar subsided, Senator Jacob Javits of New York went forward to give his commencement address. Referring to Newton, whose speech he denounced as "divisive," Javits said he offered "a different way for you to save yourselves." He outlined a "program for action" which emphasized non-violence and the legal process. Parents and students, including Newton, stood and applauded Javits' speech, though Newton felt he had been used, set up as an extremist. Newton says their speeches differed little in essence both urged non-violence, both asked seniors to take active in bettering society. "But he used me as a political whipping boy. By taking a stand as I did, I was inviting anyone to use me as a target. And, of course, it happened many, many times in the years after that."

It happened immediately. The ALUMNI MAGAZINE of October 1968 carried ten pages of "Newton Valedictory" letters, which ran seven to one against the speech. Some letters praised Newton's courage, others lauded the College for encouraging free speech and open debate. "Jamie Newton pricked the consciences of all of us, and it hurt. . . . [The speech] was a sensitive, controlled statement by a young man of conscience," wrote Arthur Kiendl Jr. '44. Most letters, however, denounced the address. Many slung epithets at Newton such as "traitor," "abject failure," "ungrateful monster," and "red-tainted antagonistic quasi-intellectual." One alumnus threatened to have Newton prosecuted as a "disgusting advocate of treason." Two sentences especially earned Newton these epithets. Most of the people in the audience ignored the part of the speech, the longest part, that called for Americans to respond to the needs of our oppressed black, tan and red minorities." Not surprisingly, they focused all their attention instead on Newton's suggestion that escape to Canada was an option for those who refused to fight, and on the phrase Newton used to emphasize the war's futility: " ... for, thank God, we are losing the Vietnam war."

"At that point quite a lot of people walked out," recalls Betty Eberhart. "You could see they were walking out because of what he had just said. That sentence was the most shocking."

"When I hear an American say he is glad we are losing the war, I do not call him an American, for I see more maimed, more dead, and a longer war," wrote Peter Barber '66 from Con Thien.

Newton now wishes he had rephrased that line, which along with the phrase about Canada, and the fact that he had a beard was recorded diligently by the wire services and sent to newspapers across the country.

JAMIE NEWTON got into a rented VW with his mother and sister and drove away from Dartmouth College, oblivious to the extent of the controversy he had spawned. While reporters searched Hanover for him, accusing the College administration of hiding him away, Newton was on his way west, soon to begin a new job as assistant peace secretary with the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker-sponsored social action group, in Pasadena, California. Newton had been offered fellowships at five universities and by the National Science Foundation upon being graduated summa cum laude, but he wanted to continue working against the war until it was over.

Newton had applied to his local draft board for conscientious objection status in 1964, but his request had been denied. He appealed. When he returned home from Dartmouth before leaving for Pasadena, the consequences of his speech became clearer: In reviewing his Selective Service file he discovered it stuffed with letters from around the country asking, Newton recalls, that he be "sent to the front lines and used as cannon fodder." Most of the letters were anonymous requests that the draft board "draft me, or offer me a choice of exile or military service as punishment for my remarks in my June 16 address." In the minutes from its July 15, 1968, meeting, the board recommended that "because of deliberately going against the government and advocating the students of his country going to another country north of us in reference to his speech made in Dartmouth College on 17 June 68 [sic] he should remain 1-A [ready for duty]." Newton appealed once more, detailing the history of his treatment by the local board, including its use of anonymous letters. The board reclassified him as a conscientious objector. Shortly thereafter, he returned his draft cards to the board, writing, "I am returning these cards and rejecting the Selective Service System's claim to authority over my life." He signed it, "No longer yours, but in peace and love, James W. Newton."

From 1968 to 1972, Newton worked with the American Friends Service Committee. All this time, Newton says, he was seeking to define his interests in life, outside the structured academic world. "I was too good a student very good at accepting an assignment and carrying it out competently but not good at identifying my own interests and acting on them. When I left Dartmouth, I didn't know what I could do. But the Quakers have a phrase, 'The way will open.' We're called to be perceptive, open, and caring. If we accept these responsibilities, trying all the time to perceive our path, 'The way will open.' "

Often introduced as a speaker on the dubious laurels of his Dartmouth valedictory, Jamie Newton sought out and spoke to audiences not predisposed to his way of thinking. At an elite men's club in Beverly Hills, California, for example, the host introduced Newton as "a real draft dodger." "I realized these people weren't picking on me because they were sadistic," recalls Newton, "but because I had hit a raw nerve. Maybe their sons were in Vietnam. To them I really was the enemy. But I believed our values were compatible they also respected and cherished freedom. I learned to speak to that commonality." In 1969, Newton went to Cuba with some members of the Friends Service Committee, then returned to the United States to talk about his experiences. After leaving the Service Committee in the spring of 1972, Newton worked for a short time helping to organize the defense for Anthony Russo and Daniel Ellsberg in the Pentagon Papers trial. Then, after four years of activism, "the way opened." Jamie Newton decided he could be most effective if he combined activism with the research and teaching of social science "getting people worried, concerned, and thinking about society." That fall, Newton went off to Stanford University.

JAMIE NEWTON is a college professor. He was a fellow in Stanford's Organizational Research Training Program. There he founded an Action Research Liaison Office to provide college students with links to the community. "I realized after I got to Stanford that there was very little relationship between the university and the surrounding community in a significant way." Through a computerbased networking system, students were matched with particular community groups in need of research and information. The student would then work for the community group, under faculty supervision, and receive academic credit at the end of the term. "We were providing students with indepth experience of community actions and community organizations which directly connected into their academic training," Newton says. "It was a first step towards combining academics with activism." The Action Research Liaison Office, which initially had to seek outside funding, is now fully supported by Stanford.

Also at Stanford, Newton helped create and taught a course named "Social Psychology in Action," to enable students "to relate social science to social action." After Stanford, Newton studied and conducted research in Australia on collective behavior. There he helped develop techniques for "systematically canvassing protest-crowds in order to achieve a group profile while the event was in progress." Newton and his six-person team would go through a rally interviewing protestors on their beliefs, motivations, and backgrounds. He reported on these techniques in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology of November 1980, in an article called "Tests of Relative Deprivation Theory in Politically Conservative Protesting Farmers." When Newton returned to the United States, he held a research appointment in the Program on Non-Profit Organizations at Yale University's Institute for Social and Policy Studies. Now, he is a tenure-track professor at San Francisco State University, developing a graduate program in social psychology, teaching undergraduates as well. Although he spends much of his time with his mother, sister, and friends, Newton is, at present, "doing almost nothing but my job."

THERE it is, the answer to my question, "What happens?" My reaction to Jamie Newton's life in academia is cynicism: What makes him any different from Abbie Hoffman, or Eldridge Cleaver, or Tom Hayden, or Mario Savio, or any of the other radicals cum stockbrokers and politicos whose political opinions seem to change with prevailing social winds? In his office in Sanborn House, Professor Peter Bien, a friend of Newton's at Dartmouth, explains the fundamental difference: "From the day he entered to the day he left, I knew Jamie first as a Quaker." As Newton himself points out, he did not "get into activism cold," but grew up in an atmosphere of social concern. Still, I ask Bien, a college professor? Articles on "Relative Deprivation Theory in Farmers"? Bien leans forward to stress a point. Two concepts basic to Quakerism in some languages there is only one word for both - are "conscience and conscientiousness." The latter means how - in your daily life, in your treatment of people you meet you exercise your conscience. "That is the important thing," says Bien, "how conscience is carried through one's life."

"My response is, 'I'm trying,' " says Newton. "In 1968, I would have criticized the person I am now for having the wrong emphasis. I would have said it's fine to do academic work but don't let it overshadow activism. Do it the other way around devote energies to activism and do academic work on the side. But I feel I'm doing the best I can to combine the two aspects of myself, and I'm making progress."

Newton sees a complementarity between his role as a social scientist and his role as a social activist. He is searching for a balance in which the activist in him reveals areas in which his skills as a social scientist could be useful. "That way I am offering more to both worlds than I can offer otherwise to either one." Newton is avowedly in transition from "training to be a good social scientist" to learning to balance his academic training with his social concerns and his personal life. "I am trying to develop a lifestyle that is sustaining. I'm only slowly learning to weave together my role as a social scientist with my role as an activist and my need for close friendships."

"Balance is not compromise," he is quick to clarify. "It is finding a dynamic partnership between two differing aspects. Everyone needs to ask: How can I do things that I'm good at and things that I enjoy in such a way that in the doing of these things I contribute to the well-being of society?"

There is still much about society that Jamie Newton thinks needs healing. He would continue to counsel young men not to register for military service, asserting that to do so is to "accept a serious deterioration of fundamental human rights." When he speaks about the nuclear arms race, or about what he calls the "multiple and interacting crises of hunger, population growth, pollution, and depleting resources," Newton regains the intensity that shows in the pictures from that commencement. But he will not confront these problems as a political activist per se. In five, ten, twenty years, Newton sees himself remaining primarily a social scientist, "teaching, reading, writing, and probably having a family." The valedictory was one example of his beliefs in action. Now he is learning to balance that action and energy with teaching and research.

WOULD the Quakers say Jamie Newton is still "speaking Truth to Power"? Inside the classroom, Newton says, he is trying to bring his students to an understanding of the social truths that guide society and the psychological motivations that guide individuals. His hope is that he will help his students become "really effective human beings." "My society had made a substantial investment in me by the time I left Dartmouth, and I feel some responsibility to provide a return on all that." Teaching is the way Newton chooses. In this light, he is little different from the James Newton who delivered the valedictory on June 16, 1968. Or from the James Newton who urged his fellow peacemarchers to see administrators and political authorities as friends - "to realize that a community of love and trust must have a place for everyone." Or the Jamie Newton who delivered his high-school salutatorian address on nuclear disarmament, or who marched in the rain at age 12 to protest neighborhood missile silos. From time to time, though, Newton admits he misses the four years of activism at the Friends Service Committee: "I felt everything I was doing was extremely useful and effective. It's more difficult for me to say that as a teacher."

The hardest part of "growing up," he says, "is realizing there are limits on what I can do, on what I can contribute. An old Quaker woman once said, 'Do less better. This was in 1962. That's what I'm still trying to do."

I last talked to Newton long distance from Hanover to Menlo Park. He was rushing off to an evangelical revival meeting to gather data for a research project on persuasive communication in crowds. I smiled - so this is James Newton, the bearded rabble-rouser whom Professor Smallwood had told us about? No, James Newton is a man struggling to find a path which will not just bridge, but join, the worlds of academia and activism. To find this "balance," Newton will have to listen to his past, as when he told a restless crowd 13 years ago to "consider what you are about." The constant questioning of the relation of one's life and work to one's belief is no easy task: More than fierce letters, threatening jeers, and weighty Selective Service files, it is the most difficult challenge Jamie Newton must face.

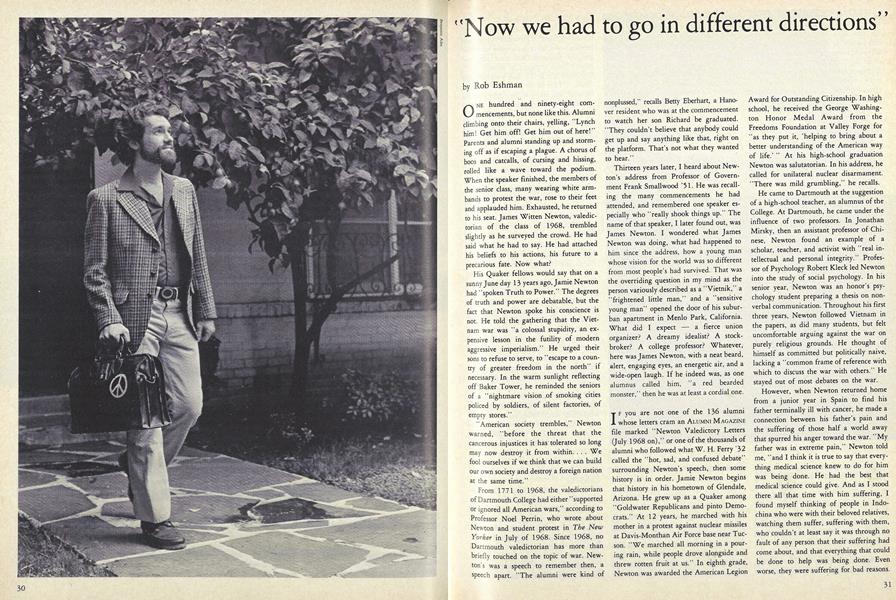

Activist Newton at commencement in 1968 and Professor Newton (opposite) in 1981

Rob Estonian wrote "Stranger in the Land,"about Charles A. Eastman, in theJanuary/February issue. Eshman, a senior,is an undergraduate editor of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA record of their fame

November 1981 By Eddie O'Brien -

Feature

FeatureB & G

November 1981 -

Article

ArticleMaster Carpenter, Journeyman Blackmailer

November 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

November 1981 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

November 1981 By Robert H. Conn -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

November 1981 By Robert D. Blake

Rob Eshman

Features

-

Feature

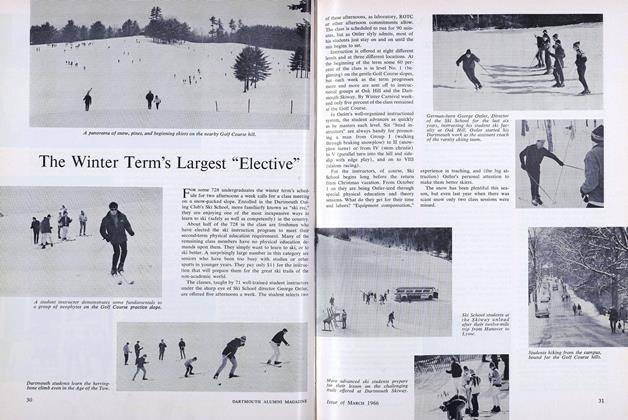

FeatureThe Winter Term's Largest "Elective"

MARCH 1966 -

Feature

FeatureSharon, Vermont (#2) $650,000

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

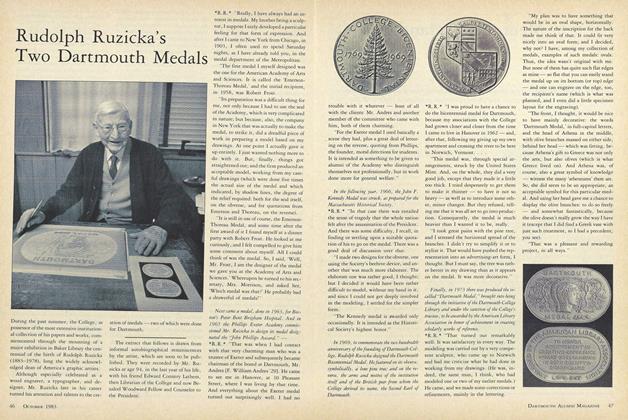

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

OCTOBER, 1908 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

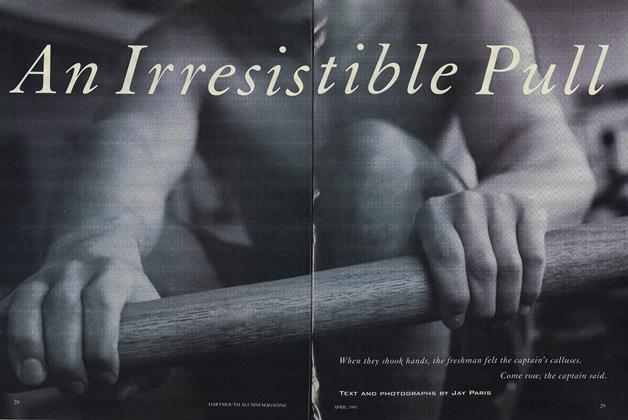

FeatureAn Irresistible Pull

April 1995 By Jay Paris -

FEATURES

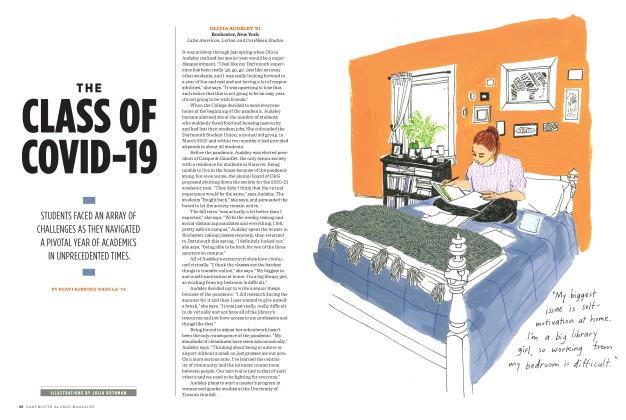

FEATURESThe Class of Covid-19

MAY | JUNE 2021 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

APRIL 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86