In the Dartmouth family, the children pay allowance to the parent. Fair enough, considering what the children can receive in return: a broad education, lifelong friendships, new directions. Of course, the children don't have to pay allowance, and not all of them do. So there must be a facilitator, someone who reminds the forgetful, chides the negligent, soothes the fretful, induces the bashful, rewards the mindful, and keeps tabs on the successful. These are the tasks of Addison L. Winship II '42. As vice president for alumni affairs and development, Winship must translate the Dartmouth sense of family into concrete institutional support. What most people define as "Dartmouth spirit" Winship must make manifest in cash. Or else, the institution that nurtures such a family, from freshman week to the last reunion, will simply not endure. Fortunately for us all, Addison L. Winship II is very good at what he does.

"All of us in development are in the posture of envying what takes place in Hanover," said Robert Seiple, Brown University's vice president for development. He was speaking primarily and rather longingly of what takes place in the Blunt Alumni Center. There, Addison Winship daily directs the Campaign for Dartmouth. As the Campaign builds to its conclusion on December 31, 1982, the statistics to date are not only enviable, but record-setting. It is the largest fund-raising drive in the College's history. Total annual private contributions today are twice what they were five years ago. No other college in the United States can boast a 62 per cent alumni giving record. Whether one measures the total number of gifts or their aggregate value, Dartmouth is a more successful fund-raiser on a per capita basis than any other college or university in the country.

For the past five years, Winship's life has been intertwined with the daily planning and operation of the Campaign for Dartmouth. On November 4, 1977, the College formally slipped into what is officially called the "campaign mode." Winship's role had begun long before this, of course, with the building of a nationwide volunteer staff that would come to number 5,000. The development staff in Hanover was expanded by 16, to 39, and all settled in for the long haul, focused on what seemed to many an arbitrary, though respectable, number $160 million. In fact, a professional consulting firm had recommended an initial campaign goal of $115 million, but Winship challenged this advice.

Total private support to the College had moved steadily, if erratically, to about $ 16 million per year since 1967, and Winship argued that with no extra effort the College could raise $ 100 million in a five-year period. He said he wasn't about to launch a massive fund-raising effort for an extra $ 15 million. "You need to get some sort of carrot - a challenge out there." At first, he recommended $140 million. Fears about inflation and confidence in increased corporate and foundation support raised the goal to the original $ 160 million. The goal was broken down into how much the College could expect to raise, based on past giving patterns, from major gift sources, bequests, parents, and smaller alumni contributions. It was prophecy founded on homework, and it became selffulfilling. In 1980, with two years to go and just $30 million shy of the mark, the trustees citing a successful campaign and a disastrous economy raised the goal to $185 million. Now, with 87 per cent of the goal reached and 80 per cent or the timeline completed, the question 's not whether the campaign will exceed its goal but by how much. "First it was 160, "hen 185- Now if you don't hit $200 million everybody starting with the president is going to be disappointed," said Winship's predecessor, George Colton '35.

WINSHIP credits his staff, the volunteers, and, most heavily, that Dartmouth sense of family for the campaign's success. For five "ungodly, insufferably long, and intense" years, the morale and commitment of the staff has remained high. He also cites the thousands of campaign volunteers, including class agents, bequest officers, and Dartmouth administrators and faculty who solicited, lectured, and entertained donors and potential donors. The motivation for this outpouring was, of course, the Dartmouth spirit. "We should never get smug about our record of support. We didn't create it," Winship has constantly reminded his staff. His emphasis has been on stewardship — maintaining the historic devotion of alumni to their college. Campaign literature doesn't ask for money as much as it "offers every member of the Dartmouth family the opportunity to participate in the campaign." This participation has been less forthcoming, admitted Winship, from faculty members and more alienated alumni groups, such as minorities and graduates of the late sixties and early seventies. Nevertheless, the overall success has been remarkable — a feat, Winship stressed, for which "no one individual is responsible. It is an institutional achievement. The common shared experience of a Dartmouth eduation," he added, "is a mystique which leaves its mark on people."

The mystique has certainly marked Addison Winship. "Ad is so emotionally wrapped up in Dartmouth. He's in love with the institution. He's the Big Green of the Big Greeners," said a close colleague. Winship's father went to Dartmouth, and there was never any doubt that the son would attend also. Winship remembers Dartmouth then as a "more cohesive Place." He attached great importance to knowing everyone in his class, and soon came to trade his rose-colored glasses for, he said, green-tinted" ones.

After Navy service and his marriage to Christine "Kiki" Hill in 1943, Winship followed a career also decided upon before he entered College - in business management. He maintained his ties to Dartmouth first as class agent, later as a member of the Alumni Council. In 1959, after cross-examining himself "one too many times," Winship decided to leave his position as regional sales representative for National Dairy Corporation. Colton, then vice president for alumni affairs and development, heard of Winship's new freedom and offered him a job in Dartmouth's development office. Colton saw himself as a planner and organizer and Winship as more of a cultivator and solicitor. "He was selling milk and ice cream for years, and by coming here he simply switched products to selling intangibles."

For Winship, the new job offered a sense of fulfillment, a chance to use his business skills for a cause he believed in: "It was essentially the sales end of the business. All your customers are people who share with you a common experience of four developing years." In 1976, Winship became vice president. He is ultimately responsible for all alumni matters class officers, the club network, Alumni College, Alumni Council, class reunions, development information, the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, and, not incidentally, fundraising. "What really counts is the cash. My job is to raise $30 to $35 million per year for the College. That's the bottom line."

Though Winship likes to think of himself as a bottom-line man, he is well aware that fund-raising demands more than a narrow focus on assets and liabilities. "Our job is'to make friends for Dartmouth College. We're in the customer service business." As it happens, making and serving friends is a good way of making money. To Winship, they are inseparable, and his colleagues marvel at the personal attention and care he gives to those who donate service or money to the College. "He operates in an old-fashioned, personal way," said a co-worker. Winship describes this aspect of his work as "resource service and booking agent." But few booking agents would write three-page "thank you" letters to donors or spend hours procuring 50-yard stadium seats and a Hanover Inn suite for a "friend" of the College stuck with reservations at a motor lodge and seats in the end zone. One recent Saturday family dinner was interrupted by a phone call from a nervous alumnus asking what he could do about his daughter's missing a deadline for an application to prep school. Winship quieted the alumnus and referred him to another College administrator who, he remembered, was well-acquainted with that particular school. Such phone calls are not uncommon, Winship admitted, but there are limits to his services. The days when a call to admissions from development improved a candidate's chances of matriculation at Dartmouth are long over, Winship said. He must explain to inquiring prospects that "the name Winship raises red flags among admissions officers. Their instinctive reaction is that all I'm interested in is money, and that's a hell of a way to run a ship."

The attention to detail (Winship is legendary for his ability to associate alumni names instantly with classes for about 10,000 alumni) is part of what one coworker called Winship's "innate sense of the best approach." It is highly personalized, discreet, but direct. "You can't pussyfoot around. People know what guys of my title or all the people who work under me, what our end product is. But the way of getting there sometimes can be slow, and properly so," said Winship. Though he denies that his office has any more knowledge of a potential donor's finances than what is publicly available, he does look into the prospect's chief concerns and closest Dartmouth ties. Donors whose money derives from, say, aeronautics may be approached by members of the Engineering Department. Wealthier prospects will often receive calls from the president or trustees. Trips to Hanover and calls from classmates or Dartmouth relatives reinforce the offer. The idea is to stimulate interest in the College "beyond what the person has shown. An approach to a person is a campaign in,itself."

Winship began one such campaign on a prospect four years ago. Three long-distance visits, numerous phone calls, two dinner parties, two presidential meetings, and much correspondence later, the College received a million-dollar gift. It is a scenario repeated, with variation, "hundreds of times." Often, it works. Many times previous donors will receive the same treatment, both by way of thanks and because "past givers are the best prospects." Winship has perfected a sensitive language to accompany his approach. He cringes to hear a fund-raiser tell a prospect, "We have you down for. ..." "Might you consider a gift of. . ." is his preferred phrase with, he pointed out, identical meaning.

FUND-raising literature, too, is carefully phrased to stress the most positive aspects of the College. Problems are typically lumped together as "challenges of the future." In one campaign brochure, the Dartmouth student body was represented by portraits of five upperclassmen: a varsity football star, a Rhodes scholar, a Reynolds scholar and chairman of the student government, a student actor with feature film credits, and a student elected to the New Hampshire House of Representatives. The potential impression is that contributions to the College help support a student body of compulsive overachievers. "The worst literature in the world to write is development literature," groaned Winship. "It's so fatuous and pompous. Every institution is 'the best place in the world.' 'The pursuit of excellence!' All those cliches!" The Horizons program, too, in which friends of the College are invited for a two-day intensive exposure to the Dartmouth experience, is apt to leave its participants with a similar, green-tinted outlook on Dartmouth life. "You can make sure the institution is presenting issues," asserted Winship, "but you cannot mix issues with fund-raising." Winship realizes, however, that the past decade has seen more issue-raising and fund-raising at Dartmouth than ever before. All of which points to a problematic, even contradictory, aspect of his position, in which Dartmouth-past conflicts with Dartmouth-present. For the image of Dartmouth that Addison Winship retains is as much a legacy of the College as it was for him and his father small, rather isolated, homogenous as it is a recognition of the many changes since then.

So, given the nature of fund-raising that is, soliciting support for a college one doesn't run with money one doesn't make - Winship has often had to seek funding for a College with whose policies he could not agree. "I'm not a policy maker," he acknowledged. "I've had to swallow some hard. But a person cannot be in my job and be a causist. You have to be reasonably moderate in your social and political stance in this job." The small ceramic Indian bust on his desk reminds one that some causes are more easily swallowed than others, yet it is Winship's conservatism, his slow approach to change, which accounts in large measure for his success as a fund-raiser.

"People with lots and lots of money tend to be conservative;" Colton pointed out.

Since Winship himself has been upset by many of the changes at the College, he is all the more able to empathize with those alumni who cannot accustom themselves to contemporary Dartmouth. "Ad has done as much as anyone I know to keep disparate members of the alumni body loving the Green," said Ron Campion '55, a longtime friend. "He's a great peacemaker." In what he calls "the care and feeding of disenchanted alumni," Winship focuses on a sense of overriding loyalty to the College. "As change comes I tend to follow it by nature of my disposition. Once I follow it, I learn that it wasn't all bad or that some of it was damn good. And then I have the opportunity to go ahead and pass that knowledge on to other people who don't live here and see the good."

"Care and feeding" also includes reassurance: When Winship read in The Dartmouth one morning that a donor's gift was used in part by "radicals and homosexuals," he was on the phone immediately, assuring the benefactor that even if there was some truth to the story, diversity in academia is all to the good. The donor was calmed. Winship bemoans the "one-issue" alumni who are unable to take "a balanced view" of the College. He is more forgiving of the legions of angry alumni who come calling after a controversial policy decision. "As long as people care enough to get upset we're not in too bad shape. There's a strong proprietary interest in the College from alumni. That's avirtue, notacurse."

"The one-on-one," between peeved alumni and himself, between potential donors and solicitors, is for Winship the "bottom line" of the campaign. But the personalized approach demands that he spend much of his time traveling, on a schedule that competes for distance and speed with the president's. After spending a week or two with local alumni groups, meeting with benefactors past and potential, having breakfast, lunch, dinner, and late-night drinks with alumni, he returns to Hanover to find a desk invariably plastered with paperwork. The work is packed up and taken home nights and weekends. If it is summer, it is stuffed into an overstuffed briefcase and taken to his summer home on Monhegan Island in Maine. Addison Winship sitting outside on Monhegan Island, briefcase and Dictaphone nesting in lap, is a familiar site, according to Colton, who has been an island neighbor. Too much," sighed Winship. "I am a slave to my job. I love it, but it is fatiguing." Winship has elected early retirement, planning to leave the College two and a half years after the campaign is over. Then, there will be more time for the family, for squash, for uninterrupted summers on the island, for painting more of the impressionist landscapes that hang on his office wall. In the off-season, he will do consulting work, and finally get around to "participating in Hanover life."

As for the campaign: "I don't think for a minute that the campaign will stop." It is not just a question of inflation, but of appetite. "Institutions are insatiable, though presumably for good causes. The camPaign is just an interlude in an ongoing development process." When George Colton's $51 million Third Century Fund was completed in 1970, the development office exhaled deeply and moved into what they call "peacetime." Now, Colton says there is no such thing. "The volunteers need a rest, of course," he said, adding that the campaign won't start up again "until January 1, 1983." Skinning the mink twice, bleeding the turnip dry, getting the last golden egg from the goose both Colton and Winship have their euphemisms for the danger inherent in such endless fund-raising. However, Winship doesn't think that a college locked in "campaign mode" will lose sight of its fundamental principles. Though many members of the Dartmouth family fear that fund-raising can too often become an end in itself, making the College fearful of risking controversy or experimenting with new programs, Winship argues that "implicit in the high figures are the costs of high-quality education" a strong teaching faculty, a more than adequate physical plant, a diverse student body, and collegesponsored extra-curricular activities. "All these things which get translated into dollars really speak to our high purpose."

It is not Addison Winship's domain to determine whether the same "high purpose" could be achieved for less cash. Others in the College establish the needs, he said, "and we go out and raise the money." The insatiable needs beget demands, which create an attitude toward the chief development officer prevalent from the trustees on down. Both Winship and Colton described it as "What have you done for us lately?" "There is the nagging feeling," reflected Winship, "that no matter how successful you are, the expectation for more keeps running on out ahead." He is quick to add that such an attitude is "the mark of a school that is going to be at the forefront." The only solution to the problem of demand, said Colton, is "to make the money come faster." "Development officers," he continued, "are not the sung heroes of the institution."

ON a clear winter's day, the view from Winship's window on the secondfloor office in Blunt includes the Hopkins Center, Parkhurst Hall, the Green, Dartmouth Hall, and Baker Library. Tilting your head up, you see the smokestack rising above the power plant, or, looking northward, the brick bulk of Mary Hitchcock Hospital through the leafless maples. Addison Winship is in the habit of swiveling his desk chair, rolling it up close until his breath frosts the window, and focusing a long gaze on these sites as he speaks. As he talks it becomes clear that he is often in the unenviable role of putting a price tag on this view. It is not for him to decide whether the College could be run for less, or with more efficiency, but to translate the spirit and symbols and values of the Dartmouth family into money. In a place where achievements are measured in terms of knowledge gained, Addison Winship's success will be summarized in the accounting books. Students, faculty, and administrators will profit from the stability of Dartmouth's large endowment. But it's doubtful they'll remember, if they ever knew, who was the man behind the money.

In Winship's case - if he takes the time to look the view is from a corner office in the BluntAlumni Center, which he dedicated(opposite) with Carleton Blunt '26 and John Kemeny in 1980.No cash changes hands among fund-raisers on the squash court - "just insults."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHotsy Totsy

April 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

April 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

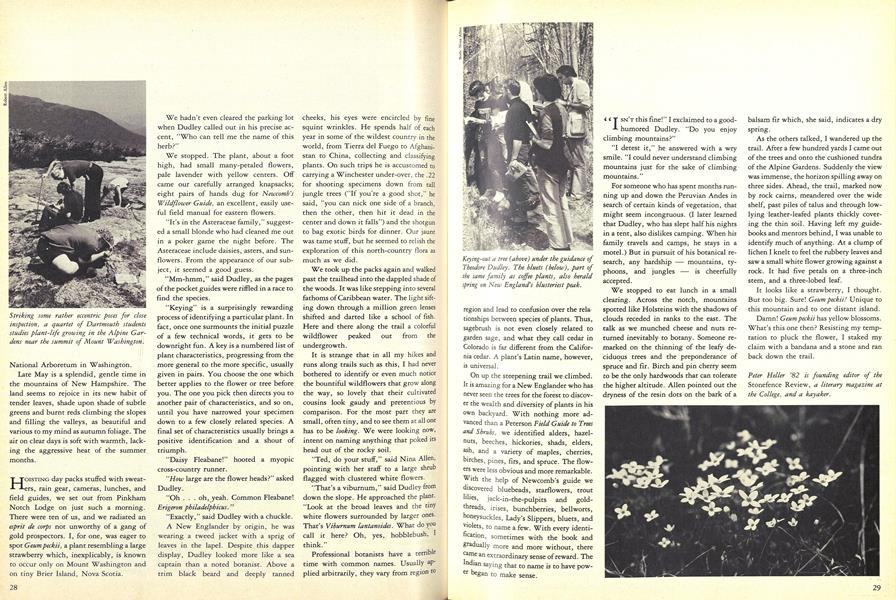

Cover StoryOn Mount Washington, where the Geum Peckii blooms and blows

April 1982 By Peter Heller -

Article

ArticleCONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL OF THE ALUMNI OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE

April 1982 -

Article

ArticleSeer in the Dark

April 1982 By Mary Ross -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

April 1982 By Robert D. Blake

Rob Eshman

Features

-

Feature

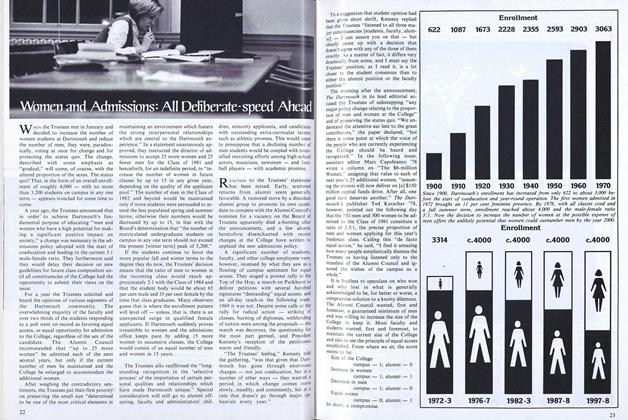

FeatureWomen and Admissions: All Deliberate-speed Ahead

March 1977 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

APRIL 1991 -

Feature

FeatureSMITH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

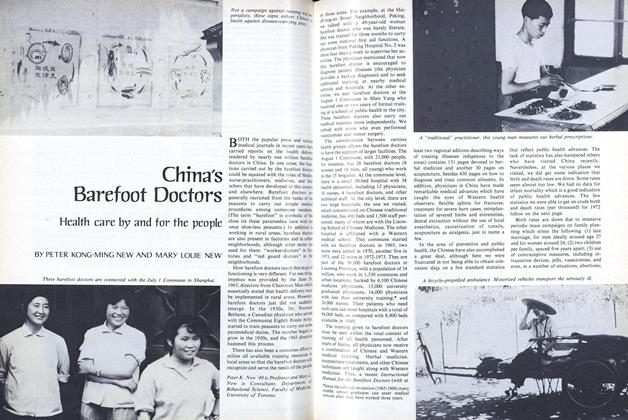

FeatureChina's Barefoot Doctors

June 1974 By PETER KONG-MING NEW AND MARY LOUIE NEW -

Cover Story

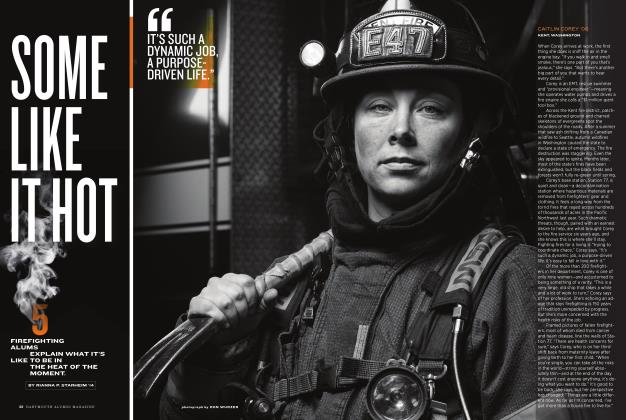

Cover StorySome Like It Hot

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By RIANNA P. STARHEIM '14